In Charles C.W. Cooke’s fantastic piece in National Review last week on the power of emotion in the gun debate, he made an excellent point; facts and statistics aren’t enough to really win this battle. There’s a real, living, breathing emotional case to be made for the Second Amendment. And while Real Americans have been winning the factual, statistical and legal case for decades, we need to win the emotional case – the case that speaks to America’s heart and gut and liver – before we can really relegate gun control to the shallow intellectual grave it belongs in.

History Repeats: A longtime friend of this blog, long known as “Buddhapatriot”, a charter MOB member, sent me a poem the other day.

It’s from a post he wrote a couple years back:

Last year the edict forbidding us to ride horseback;

This year another edict saying we cannot carry a bow.

Yet we still hear about all those robbers who by the light of day

Ride their horses and shoot people on the empire’s highway.

Technology aside, it looks like it could have been written by anyone in Chicago, slaving away under a de facto gun ban as hoodlums shoot up his neighborhood. It could even have been Otis McDonald himself.

But it was written in China, under Mongol occupation, in the 1300s.

Some things never change.

Numbers: When America was founded, there was really no such thing as a municipal police force. County sheriffs – with their strictly limited powers, and their volunteer posses – were often days away if trouble sprang up.

And yet crime in America, as a general rule, was exceptionally low.

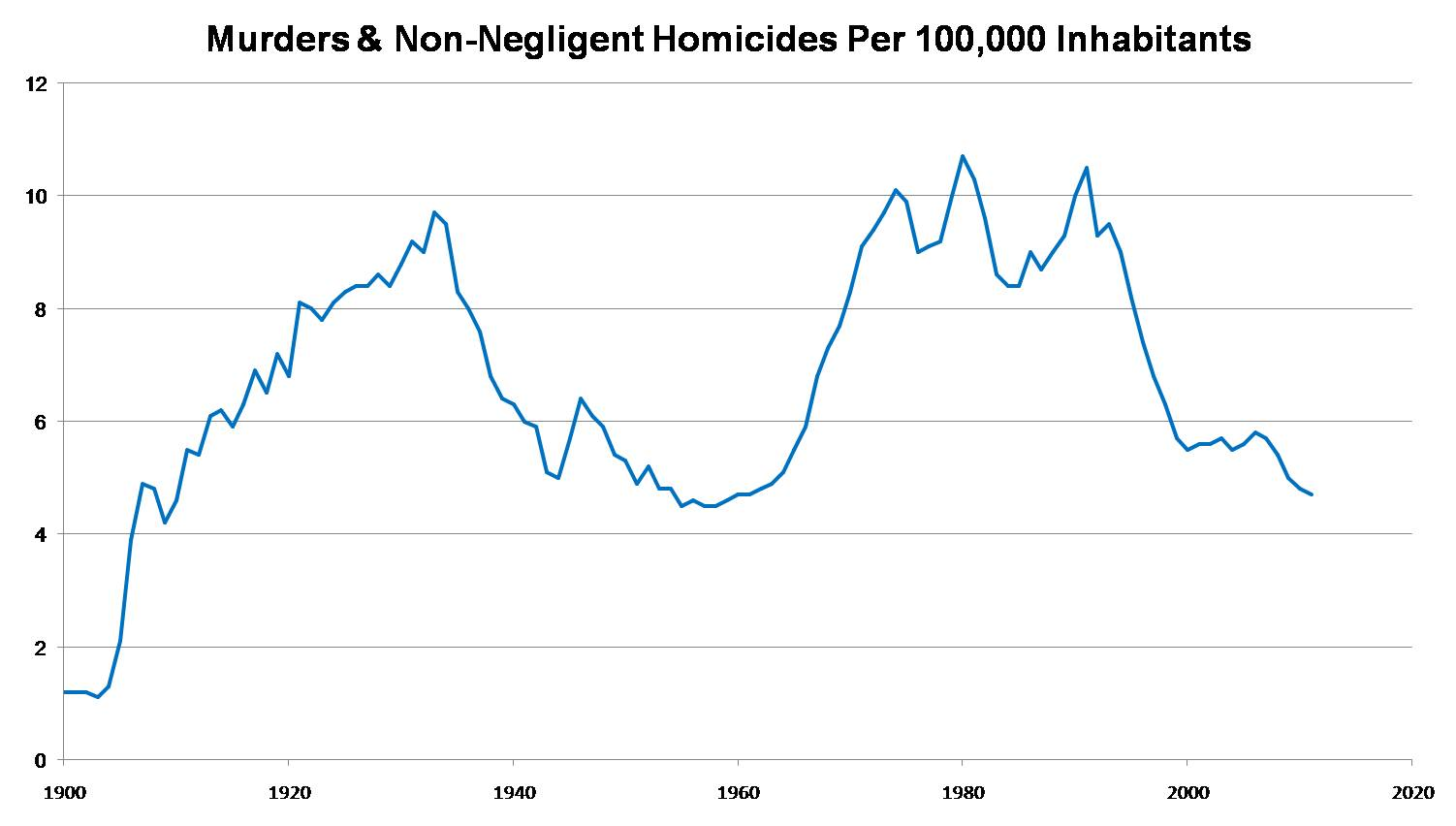

That changed, somewhere along the way, of course. About 100 years go, a variety of factors – urban crime, Prohibition and the concomitant explosion in organized crime and turf-protection murders – and then the War on Drugs and the 1968 Gun Control Act all correlated with massive surges in criminal homicide.

Do It Yourself: Real Americans have always had an organic sense of law-enforcement; civic responsibility is part and parcel of participatory democracy.

And it’s by no means a given everywhere in the world. Attitudes of civilians and citizens toward “law enforcement” vary widely, even wildly, around the world – and for good reason, since “enforcing the laws” (or engaging in a sham version of it) is often accompanied by brutal tactics, unaccountable power, and stunning, stunting corruption. Worse than Chicago, even.

Even in “democracies”, the role of the citizen versus “law enforcement” is sometimes – for lack of a better term – brain-damaged.

As, indeed, it was in the United States. At the nadir of the gun debate in the late seventies and early eighties, as major cities were enacting de facto or de jure gun bans, the individual right to self-defense was very much on the ropes.

I remember reading advice to people living in major cities in the seventies, urging people to carry a “mugging” wallet, with a little money – not too much to break you, not so little that the mugger would get angry – to give to muggers when you got stuck up. It was an abdication of our streets to our criminals – the smarter among us knew it.

Some New Yorkers are nostalgic for the Lindsay and Dinkins years. I suspect they may be the type of people who look forward to colonoscopies and tax audits.

And at the very nadir of that awful period came Bernard Goetz – who, sick and tired of the regular mugging, carried a gun. It was against the law, of course – unless you had the political clout to get a carry permit, which many media and business figures did for the asking.

But not Goetz. The humble electrical engineer, mugged one time too many, shot his way out of a jam in the New York subway in 1984.

The police arrested him, and New York’s pencil-necked, pasty, pusillanimous prosecutors, operating at the behest of an administration that figured armed criminals was better than safe people, prosecuted Goetz to the fullest extent of the law.

And a funny thing happened; America – even New York City’s cowed, pseudo-European subjects – feted Goetz as a folk hero. Oh, the establishment media reviled Goetz, of course; What’ll happen if regular schnooks kill all the criminals, they gasped.

But Real America looked at Goetz, I think, and they saw…

…themselves.

In the early eighties, at the nadir of the American right to keep and bear arms, and the peak of the urban crime wave that only started to break 20 years ago, it was very easy to identify with Goetz; robbed over and over, first by street thugs, and then by thugs with law degrees or working for newspapers, Goetz’ situation reflected a lot of peoples’ fears – and his response sparked a lot of imaginations.

It may be uncaused correlation, a complete coincidence, that on the day Bernard Goetz shot his muggers, exactly eight states had “shall issue” laws, requiring states to prove one should not have a permit to carry a firearm; by 1990, it was 15; by the 10th anniversary of his trial, 20; today, 42 of the fifty states have either “Shall Issue” or “Constitutional Carry”.

Was Bernard Goetz the cause celebre that led, slowly and circuitously, to the state we’re in today, with Real Americans in the ascendant?

I like to think they’re related. Prove me wrong.

Beyond The Stats: The statistics of civilian gun ownership in combating crime have been part of the diet on this blog since Day 1` – literally.

But beyond the numbers and the charts and the books?

Americans (of Korean descent) protecting their property and lives during the LA Riots. If this doesn’t make you proud to be an American, then you need both heart and brain transplants.

There might be people in this country who don’t crack a smile when a typical schnook with a gun saves dozens of lives; whose step doesn’t quicken when the little woman with the kids repels the big bad robber; whose hearts don’t well up with pride when regular American schnooks seize order from disorder, as Los Angeles’ Korean shopkeepers did during the 1992 riots; They might exist.

But they’re not my countrymen.

We are a nation, historically, that treats “keeping order” as a community activity. And the message is getting out to The People, a majority of whom now believe that civilian carry makes us all safer.

May it ever be so.

That’s why we’re here.

To Sum It Up In A Sentence: Americans were never intended to be helpless in the face of evil.

This Series:

- Part I: “History“

- Part II: Enemies Foreign and Domestic

- Part III: The Public Good

- Part IV, Tomorrow: The Underdog

“Oh, the establishment media reviled Goetz, of course”

Ruling elites don’t ride the subway. Ruling elites don’t live on blocks with section 8 housing. Ruling elites don’t send their kids to inner city public schools.

The echoes of the footsteps of Genghis Khan are still being heard through much of Eurasia. He is indeed the baddest man that ever was, and the devastating effect his terror had on the morale of all of those conquered lands has flavored geopolitics ever since. You can divide the world into those areas conquered by the Mongols, and those areas not conquered which flourished with the European Enlightenment and the 30 Years War or were colonized militarily and culturally by the Europeans. The 30 Years War taught the Europeans that the greatest threat to peace and prosperity came from total war over petty differences, particularly religious ones, and that a structured system of nation states with limited wars between armies preserved wealth and progress (until WWI, at least). The Mongol conquered region of Eurasia never forgot that an outsider could suddenly appear at your doorstep and obliterate everything that you know, your entire people, so beware the outsider, hunker down, and prepare for his invasion. Those two differing worldviews are why much of the modern world is what it is.

This is good too, why liberals can’t have minority groups assimilare. Solid read…http://www.nationalreview.com/article/429676/obama-race-relations-lousy

This is good too, why liberals can’t have minority groups assimilare. Solid read…http://www.nationalreview.com/article/429676/obama-race-relations-lousy

Emery-

The father of modern scholarly history is Charles Beard (1874-1948). Beard taught that the past is not real. History is just current thought about this thing with nominal existence called the past. History, then, was more like literature than like archaeology. This works only in the modern world. In the pre-modern world, the past was real because it was reality as known to God, whose every thought is Truth and who dwells in eternity. History would have been an attempt to describe past events as God knows them to be.

When you write “The 30 Years War taught the Europeans that the greatest threat to peace and prosperity came from total war over petty differences” you are engaging in an interesting bit of narrative. The differences were not petty to the people who lived at the time. Despite what Swift wrote, the dispute was far more profound than whether a boiled egg should be cracked on its blunt or its pointed end.

Catholics believed in free will. You could ensure your own salvation by choosing to do certain things. To the protestants (esp. after Calvin) mankind was utterly evil and incapable of doing anything to save himself. To play the Catholic game of Good Works implied that the fallen creature, Man, could ‘pull one over’ on God. To say that men could act to save themselves was to limit the power of God. This difference is what the last pope was refering to when he compared Protestants to Muslims (FYI, I am a Protestant).

This conflict is with us today. Do bad people choose to commit crime (the Right) or do they commit crimes because social circumstances beyond their control caused them to commit crimes (the Left).

These were not petty differences. In Catholicism God is the source of reason. All use of reason will lead you to God. To the Protestants, reason was vanity when applied to God. To the Protestants, however, applying reason to the world of the senses might have positive results . . .

Before the reformation, the natural world was chaotic and not understandable by reason, but God was understandable by reason. After the reformation, the natural world was understandable by reason, but God was not.

What ended the religious wars of the 16th-18th century in Europe was not the Europeans learning to discard petty differences of religious doctrine, but their learning to elevate national identity above religious identity.

An honest look at what the people who lived back then wrote and argued shows that fealty to religion was not replaced by fealty to moderate compromise, but that fealty to relgion was made subordinate to fealty to nation.

The Muslim Enlightenment or Islamic Golden Age ended with the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258. The Abbasid Caliphate (Dynasty, basically) had ruled since the early turbulent years of Islam and had seen the reach of Islam extend to what is now Pakistan and Spain. The empire was fairly centralized, particularly intellectually, and when Hulagu and his Mongol army (under Genghis Khan) destroyed Baghdad, he killed hundreds of thousands, including most of the leading philosophers, artists and intellectuals, their great libraries and storehouses of wealth and wisdom. While the Mongol tide retreated soon after, the successors of the Abbasids, in particular the Ottomans (Steppe people who descended in part from Mongol conquerors), were much more conservative and remain so to this day.

The shock of the Mongol terror had a profound effect on politics and culture in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, and arguably all of the lands they conquered, including China. The fear and horror generated served to create a culture of fearful conservatism, distrust of the outsider, and an insecure need for a dominant military, that extends to today in Persia, the Levant, and Russia. China is a little different, as the Chinese assimilated the conquering Mongol culture into their own, so the effect there is less of the fearful conservatism of the conquered, and more of the disdainful arrogance of the conqueror.

Kissinger’s “World Order” talks about post-Treaty of Westphalia Europe, and the system of states that it produced. It also discusses some of the non-European powers, and how they differ in their outlook on the world and how powers should interact, specifically the Muslim world, the Russians and the Chinese. Fukuyama’s “Origins of Political Order” goes into how different systems of government evolved. You can find various histories of the conquests of Genghis Khan, but a good summary can be had by listening to the Dan Carlin Hardcore History Podcasts “Wrath of the Khans 1-5”. I recommend all three if you have an interest in history and geopolitics and you have the time (they’re big books, and the 5 podcasts probably total 15 hours).

E,

All roads seem to be driving me toward listening to Carlin.

Pingback: Why We Fight, Part IV: The Underdog | Shot in the Dark

But Mitch, you already know those words you can’t say on TV, I’m sure!

I remember cheering for Bernhard Goetz back as a young skull full of mush.

Pingback: In The Mailbox: 01.18.16 : The Other McCain