There was no Christmas cheer among the soldiers marching to the Reichskanzlei (Chancellery) in Berlin on December 23rd, 1918. The men were from the Volksmarinedivision, the revolutionary paramilitary unit created, in theory, to defend the newly established Council of the People’s Deputies and the burgeoning German leftist revolution. In reality, the Volksmarinedivision was closer to the Independent Social Democrats and the so-called “Spartacists”; the more militant wings of the new government that preached a political gospel similar to that of Russia’s Bolsheviks. The Volksmarinedivision had ransacked the Kaiser’s old Berlin residence, the Stadtschloss, and encamped themselves there after looting or destroying much of the historic artwork of the building. The Council of the People’s Deputies had protested the division’s actions, seeing them increasingly more as hooligans than soldiers. In response, the Council ordered the Volksmarinedivision out of Berlin and to dismiss all but 600 of their men. When the paramilitary group refused, the Council stopped their paychecks.

Lieutenant Heinrich Dorrenbach, the group’s commander and close ally to Karl Liebknecht of the Spartacus League, marched on the Reichskanzlei ostensibly to follow orders – he had the keys to the Stadtschloss in hand and was prepared to reduce his forces and leave the city, provided the government issue their backpay. But no German politician would claim that they were authorized to pay Dorrenbach and his men, deferring the decision to Berlin’s Chancellor and the Chairman of the Council, Friedrich Ebert. Ebert had no patience for the Volksmarinedivision, whom he considered thuggish radicals led by a “rootless adventurer.” The issue of the Volksmarinedivision had been one of many that was quickly dividing the new government, and Ebert was vainly trying to mollify both the political left and right in his ad hoc administration. Whether Ebert intended to pay the Volksmarinedivision eventually or not, he wasn’t going to be threatened into a decision.

Dorrenbach had his answer. His men swarmed the Reichskanzlei, blocking the doors and access roads. Another contingent marched to the Kommandantenhaus, the military headquarters for the city, looking to capture the city’s military commander, the politician Otto Wels. The building’s guard, regular army troops, resisted and shots were fired. It didn’t matter. The superior numbers of the Volksmarinedivision had overwhelmed the government, taking Wels and other key political figures hostage. The moment that Ebert and many members of the Council of the People’s Deputies had tried to avoid had arrived – the German revolution was about to turn bloody.

Karl Liebknecht – Germany’s Lenin, at least in the eyes of many. He lacked Lenin’s ruthlessness or political savvy, having often to be dragged along into decisions affecting the revolution

From the very beginning of the chaotic German end to the war, there was a fear in Berlin (and indeed, across Europe) that Germany was quickly staging their own rendition of the Russian revolution.

As in Russia, the monarchy had collapsed and with it, most sense of civilian control. Worker’s councils (Soviets in Russia; Rates in Germany) had risen up across the empire and seized control, often with the support of rebelling soldiers and/or sailors. The legislative remnants of the prior regime had technically assumed power, but held little public support and were immediately being undermined by a sort of dual authority between the government and the most radical elements of the leftist/Communist organizers who preached worldwide, violent socialist revolution. The actors may have changed but the play seemed remarkably the same.

But Germany of late 1918 was not Russia of 1917. Conditions within the country were most certainly horrible, with caloric intakes of civilians down to an estimated 1,000 per day, sailors and rebels having captured many of the northern port cities and the former military and civilian leaders of the nation gone or quiet. Nor did it help that the most prominent man in Germany, Paul von Hindenburg, whom most sides in the nation still trusted and respected, had retired to an inn in Kassel and although still technically in charge of the military, said or did almost nothing, commenting that he felt he had no voice to offer having “lost the greatest war in history.”

Rebels in front of the Chancellery

The political leadership that did remain initially appeared to be going down the same path as the Russian Provisional Government, as the Reichstag essentially yielded authority to the Council of the People’s Deputies much as the Provisional Government allowed the Soviets to occupy an increasing number of posts of authority. But Chancellor/Chairman Friedrich Ebert was determined not to become a German Alexander Kerensky. Ebert’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) had been the majority political party in Germany since 1912, as the overwhelming number of seats in the Reichstag were held by either liberals or left-leaning centrists. And while the war had slowly fractured the SPD’s governing alliance and the SPD itself into two parties, the SPD and the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) which included the much more radical members of the parliament, Ebert had the history, relationships and relative skill to weave together a makeshift government. Ebert could also be politically ruthless. As Germany fell apart in the war’s final days, he successfully forced Chancellor Max von Baden to appoint him his successor (despite having no constitutional authority to do so) and sent members of the rival Catholic Centre Party to sign the Armistice instead of Ebert himself or any SPD official.

By the politics of 1914, Ebert might have been considered a “radical.” Such were the conservative leanings of even the nominally liberal Reichstag that there was significant discussion was whether or not Ebert and the SPD might be arrested and the party disbanded, despite the SPD holding a plurality of parliament with 35% and 110 seats. Instead, Ebert toed the line and helped deliver a unanimous SPD vote for war bonds in August 1914. Even eventual Spartacus League leader Karl Liebknecht didn’t oppose the vote, rationalizing that Germany was fighting an even more autocratic regime in Tsarist Russia. Kaiser Wilhelm II was so ecstatic with the result that he told the Reichstag “I no longer see parties, I see only Germans!” Ebert the “radical” was now Ebert the “moderate”, a position only reinforced as the SPD began to split, with the USPD speaking approvingly of the Russian Revolution while the SPD insisted on denouncing the violence and revolutionary spirit of the Bolsheviks, despite their own pronouncements against the dictatorial bent of the German war effort.

Such a reputation would allow Ebert to gain power but not trust. Both the SPD and USPD declared republics on November 9th, 1918 – but only the USPD’s Karl Liebknecht’s declaration was for a Socialist Republic along the lines of the Bolshevik revolution. Ebert managed to convince the USPD into a power-sharing agreement, co-opting the Council of the People’s Deputies and placing himself as Chairman. Having at least temporarily blocked opposition to his left, Ebert worked to solidify his right, reaching an agreement with Wilhelm Groener, Quartermaster General of the German Army, gaining military support for the Council while pledging to allow the military to remain semi-autonomous.

Freikorps – the name had a long lineage of German mercenary work stretching back over centuries, but the Freikorps of post war Germany were more of a violent militia, often opposing both the revolutionaries and the new government

On paper, Ebert had deftly mollified the various factions of Germany, buying time to solidify a more democratic nation that had appeared on the verge of civil war in early November. But he had done so by weakening his future authority at every turn. The Rates and their paramilitary wings were a part of the government but didn’t exactly view themselves as subject to Berlin’s control while they expected revolutionary reform measures in return for their lack of violence. Elements of the German nation had all but officially broken away as Socialist Republics in Bavaria and Bremen formed their own governments. The military kept waiting for the Council’s mask to drop, revealing it’s Bolshevik tendencies, and refused to commit what forces remained to crushing the Council’s domestic opponents. Hindenburg himself preferred to support the independent Freikorps, which had essentially become the conservative alternative to the Volksmarinedivision. The Freikorps rallied many veterans in the wake of the German revolution, initially fighting against Communism both within Germany and in the Baltic states, keeping up the historic definition of the term as a German mercenary. But the Freikorps quickly grew to distrust the government as well, and like the Volksmarinedivision were both a part of and separate from the government, meaning that two rival paramilitary groups were in control of domestic policing. In his efforts to avoiding looking like the Russian Provisional Government, Ebert had followed them to a tee in one overarching respect – it was a government directly in charge of almost nothing.

As the Reichskanzlei was being seized and the government taken hostage, Ebert had managed to contact the Army High Command at Kessel. The High Command had rational reasons to not want their regular soldiers in street-level fighting between political factions, beyond just Hindenburg’s private declarations for the Freikorps or the military’s mistrust of the Council’s motivations. Just weeks earlier, the High Command had reluctantly assigned 10 divisions worth of men to Berlin to “restore law and order.” The divisions had effectively melted away, deserting in record numbers. Only 800 troops of the original 10 divisions remained combat ready. To put that into a sense of scale, by the end of the war a German division (if healthy, which basically none were) might be 10,000 men – meaning that over 90% of the assigned military to Berlin either abandoned their post or were physically unable to fight. It’s reasonable to assess that the German military didn’t want to choose sides in large part because they were too weak to engage in open warfare (also likely why Hindenburg supported the Freikorps over the regular army in some insistences).

Outnumbered, the regular army soldiers still had much more experience and heavy artillery, while the Volksmarinedivision only held a couple hundred more men. The regular army’s shelling quickly brought out the civilian populace, at first begging for the army to stop firing, and then soon opening fire themselves on the troops. Even members of the 800 soldiers sent to depose the Volksmarinedivision began to switch sides. By noon on December 24th, with the army’s position falling apart and now even Berlin’s police shooting at them, a ceasefire was called. The remaining soldiers would leave the capital and the Volksmarinedivision would get their full pay, plus not have to reduce their numbers. It was an embarrassing defeat for Ebert and the government.

Socialist revolutionaries take up a machine gun post

The Spartacist press and their leader Karl Liebknecht immediately called the battle “Eberts Blutweihnacht” (“Ebert’s Bloody Christmas”). The exodus of leftist leadership from the Council would quickly follow, with most of the USPD leaving the coalition government and Liebknecht and the Spartacists declaring the creation of the Communist Party of Germany, seeking recognition from Lenin’s Bolsheviks. The mood on the streets was, if anything, even more hostile to Ebert and the Council, as the funerals for the few dozen dead Volksmarinedivision turned into massive protests calling Ebert and the Council “traitors” and “murderers.” It would appear that the collapse of Ebert’s government would happen within days, if not even sooner. In addition to the “Christmas Crisis” as it would be known, Russian Bolsheviks were invading the German-allied Baltic States, Polish insurgents would start the Posnanian War or Uprising at year’s end, successfully occupying German Polish lands, and a Rhineland separatist movement would be launched. And that was just by the end of 1918.

If the fear in Germany was that Friedrich Ebert would become the nation’s Alexander Kerensky, it was widely assumed that Karl Liebknecht was the Reich’s version of Vladimir Lenin.

Liebknecht had been a member of the Reichstag with the SPD (his father had been one of the founders of the party) and while he never voted in favor of the war effort, was initially quiet about his opposition. His co-founding of the Spartacus League with Rosa Luxemburg, one of the most prominent female political activists in the world (who actually taught Marxism and economics in Berlin to Friedrich Ebert), would lead to his literal and figurative political exile, as Liebknecht was arrested and sent to the Eastern front, digging graves. Liebknecht’s return from such punitive punishment saw him take to the floor of the Reichstag and denounce the Armenian genocide, leading him to be dismissed from the SPD and eventually arrested under the charge of high treason for his anti-war activism. Only Max von Baden’s amnesty for political prisoners would free Liebknecht, who immediately resumed his leadership of the Spartacists with Luxemburg and declared a Socialist Republic.

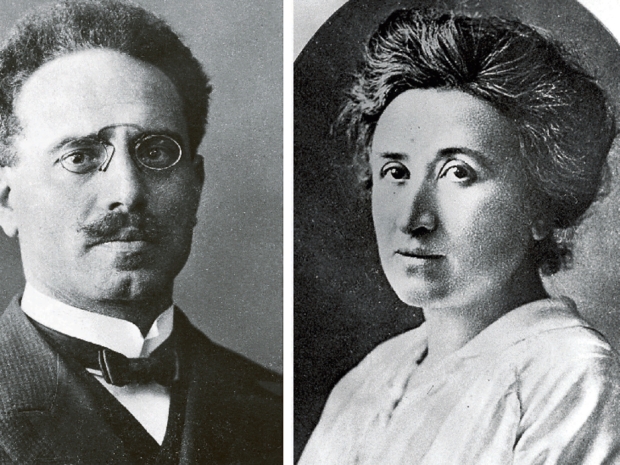

Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg – the two prominent leaders of the German revolution

But simply put, Liebknecht was no Lenin. Nor was Luxemburg, as the two engaged in a philosophical battle for the direction of the Spartacist movement and larger communist revolution. Liebknecht hoped for some vague “street-level” revolution that would sweep the Spartacists into power. Luxemburg argued that only political participation could lead to gaining the popular support needed for revolutionary change. Neither was overtly willing to denounce or support violence to achieve their aims. As such, despite the mood on the streets on Berlin and the political winds blowing at their backs, fewer and fewer leftists wanted to listen to two activists who seemed more about speeches than concrete actions.

Indeed, even the denouement of the German revolution would occur largely outside of the Spartacist’s influence. Ebert’s government attempted to remove Berlin’s Chief of Police on January 4th, 1919 for siding with the Volksmarinedivision during the Christmas Crisis. The result was hundreds of thousands of protests spilling into the streets of Berlin, with an increasing number of them armed. The protestors began to occupy train stations and opposition newspaper publishers, all the while the Spartacist leadership tried to get them to stop. Sensing the momentum, Liebknecht declared a general strike in Berlin with the goal of overthrowing the Ebert government. The call to strike brought half a million workers into downtown Berlin but the call for revolution went unheeded. Even the Volksmarinedivision hesitated to join.

Ebert had his moment. Like Kerensky in the “July Days” crisis of 1917, Ebert had the support of the military and the German middle and upper classes to put down those calling for open, violent revolution. Unlike Kerensky, there wasn’t going to be much mercy for such revolutionaries. Ebert requested 3,000 Freikorps volunteers to put down the “Spartacist Uprising” and had the SPD’s newspaper write headlines calling for the execution of Spartacist activists. With the paramilitary wings of the revolution unwilling to fight, the Freikorps regained control of Berlin within days, all for the cost of less than 200 dead.

Berlin’s Red Guard marches through the streets

Liebknecht and Luxemburg would be rounded up in the following days, having been unable to escape the city. There would be no trial. Both were beaten, tortured and then shot by Freikorps troops. The message was unmistakable – Germany would no longer tolerate revolutionary fervor.

For an event that looked as though it was about to usher in a Communist Germany, the Christmas Crisis of 1918 ended up bringing about the nation’s first genuinely democratically elected government.

While Ebert had desperately sought to avoid a civil war, the fracturing of the Council of the People’s Deputies had pushed the revolutionary elements of the Council out of power and allowed the government a free, if terribly bloodied, hand to sweep the Spartacists and their supporters aside. The handling of the Spartacist Uprising outraged many within the country, and certainly Ebert knew full well of the thuggish actions of the Freikorps, but the political left was too divided and German society at large still too uncomfortable with the thought of revolution, to do much about it. Ebert would utilize the Freikorps to put down the other Socialist Republics in the country, although the overthrow of the Bavarian Soviet Republic in the spring of 1919 would end up an even bloodier affair with executed royal hostages, hundreds of casualties and then over a thousand shot political prisoners.

Friedrich Ebert – the first President of the Weimar Republic. Having put down a leftist attempt at a coup, Ebert would spent the next several years having to do the same to a handful of right-led coup attempts, including one by the Friekorps and the Beer Hall Putsch by Erich Ludendorff and Adolf Hitler

But out of the blood would emerge an elected German Republic – the Weimar Republic – with Ebert as it’s first President. The Weimar Republic would face repeated challenges from the left and then the right, and ultimately go down in the history books as a failure, but for the first time in the history of Germany since unification, it’s executive leadership was common, civilian and democratic.

There was more than enough evidence to justify destroying the Soviet Union after the end of WWII. It’s a pity our guys were worn out by that time, and our leaders lost their will.

There are generally two ways of looking at the Hitler/Nazism phenomenon. In the first, Hitler/Nazism is viewed as a unique historical occurrence. Hitler was uniquely evil, and the German people of 1932-1945 were also uniquely evil in making him their national leader.

In the second, Hitler/Nazism is seen as just another bloody van in the grim parade of human history, made all the more wicked by modern technology, and the 19th century invention of the centralized, secular state.

The conflict between the Freikorps and the Volksmarinedivision tends to support the latter view. The choice the German people made, 1918-1932, was not between Nazism and Democracy, but between Nazism and an equally grotesque Stalinism.

Hitler was uniquely evil, and the German people of 1932-1945 were also uniquely evil in making him their national leader.

MP, Stalin and the Bolsheviks, Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, the “Young Turks”, Idi Amin, Shōwa Era Japan (1895-1945), the population of Haiti from 1804 to present, Chairman Mao and the Kim family called, and they’re pretty upset at your snub.

Hitler/Nazism was inevitable from the historical perspective. Fact that soci@lism took root in Russia and not in Germany is a conundrum. Alas, not enough people study what made one inevitable while the other accidental and we keep repeating the same mistakes, over and over, costing lives in the process. It’s like there is a malthusian cabal writing the script or something…

FR, excellent and fascinating read as always. Thank you!

Hitler/Nazism was inevitable from the historical perspective.

That is 100% accurate, from multiple historical perspectives. It was foreseen by many.

Well done, FR. It’s fascinating how these obscure and relatively unknown periods of time have such a great effect afterwards.

BTW. I was amiss in not acknowledging the excellent post, First Ringer.

Well done and appreciated

Pingback: In The Mailbox: 05.11.22 : The Other McCain

Pingback: Ravenous | Shot in the Dark