We’ve fallen a little behind on our World War I series. Over the next few months, we’re going to work to get caught-up to the calendar.

Cramped in the rail-yard of the Pskov station, the Tsar’s Imperial Train made for quite a sight. The train carried ten carriages: a sleeping-car for the Tsar and Tsarina, a saloon car, a kitchen, a dining car, carriages intended for the grand dukes and other family, the children’s car, cars for the Tsar’s retinue, as well as cars for railway servicemen, servants, luggage and workshops. The ornately designed cars stood out like a sore thumb amid the largely industrial city.

But on midnight of March 15th, 1917 (or March 2nd, by the old Russian Gregorian calendar), the attention of the citizens and soldiers of Pskov were not on the garish train, but it’s occupant – Tsar Nicholas II. Having rushed back from his command headquarters in Mogilev, some 400 miles away from St. Petersburg/Petrograd, at the repeated urging of the capital’s political and military leadership, Nicholas II found his path home blocked by rebelling soldiers. Instead of arriving back at his seat of power, Nicholas II had been forced to retreat to Pskov.

Three days earlier, Nicholas had fumed with indignation that the Chairman of the Duma had described the scene in St. Petersburg as “anarchy.” The Tsar called such warnings “nonsense,” declaring he wouldn’t even reply to such communications. Now, Nicholas II’s military and Duma allies were grimly explaining the consequences of the Tsar’s inaction. St. Petersburg was completely in control of the rebels and a makeshift coalition of forces there had declared themselves the legitimate Provisional Government of Russia. Further violent crackdowns seemed out of the question. Any federal troops sent to St. Petersburg only joined the rebels.

Tsar Nicholas II asked Army Chief Nikolai Ruzsky what he should do. “Abdicate,” Ruzsky replied. Hesitating for but a few moments, Nicholas agreed. Russia’s 370 years of Tsarist rule was about to end.

By the spring of 1917, the surprise was not that Tsarist Russia collapsed, but that it had endured for as long as it did.

The empire’s infrastructure, already badly outdated by 1914, had crumbled under the strain of the war. Civilians were waiting the equivalent of a full-time job in food lines alone, if they were even able to afford food given the rampant inflation that had doubled prices since the start of the war. The purchasing power of the ruble had fallen to 30% of its former value while the national debt had jumped from 3 billion rubles to 11 billion rubles. Most of Russia’s operating income now came in the form of loans from their allies. Even those numbers likely underestimated the true cost of the war to Russia’s economy as modern adjusted figures suggest the conflict cost the Tsarist regime up to 50 billion rubles.

The cost in human terms was even worse. Russia was on it’s way to over 9 million casualties – roughly 76.3% of their entire mobilized force. By 1917, 1.5 million Russian troops had deserted while another 1.29 million would fall ill within the next 12 months due to disease and malnutrition. Despite the victories of the Brusilov Offensive the previous summer and early fall, the morale of the Russian army was all but nonexistent.

The deteriorating condition of the empire extended into the nation’s monarchy and political leadership. Tsar Nicholas II had isolated himself – literally and figuratively – by choosing to directly lead his armies at Mogilev while leaving his Germanic wife to rule in St. Petersburg in his stead. The Duma he had left behind had little actual governing authority, and had actively pressed him to embrace Constitutional reforms. When even the conservative Duma factions allied themselves with the body’s liberals in 1915, Nicholas II began to contemplate dismissing them entirely.

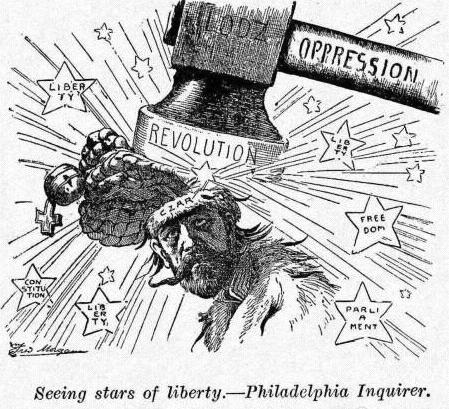

Despite years of warnings from his fellow members of nobility and his dwindling allies in the Duma, Nicholas II took no actions other than increasing the use of force. News of strikes, riots and mutiny were nothing new under the Tsars. Indeed, the empire had seemingly faced a worse crisis during the 1905 Revolution, which saw the Romanovs emerge barely victorious after more than two years of bloodshed, but with their power somewhat curtailed with the creation of the Russian Constitution and the Imperial Duma. Nicholas II had considered both moves to be mistakes that were largely responsible for the dissension in the general populace. He was determined to not repeat the errors by enabling further democratic reforms.

The Tsars had largely maintained their rule by the unity among the ranks of the nobility and officer corps. After two and a half years of war, Nicholas II had badly overestimated the strength of either group.

Perhaps the surest sign of the weakness of the Tsarist Empire was that as it tottered, almost no one came to its defense.

While the number of strikes, and number of participants, had grown in St. Petersburg, for the first time average soldiers had joined the protesters. Members of the Duma now openly talked about the need for the Tsar to step aside while royalists like Prince Georgy Lvov began to conspire with Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich Romanov – the former Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army – about seizing control. Across St. Petersburg, everyone was talking about the need to replace the Tsar, but no one appeared willing to take the first step.

The winter of 1917 at first delayed, and then exacerbated, the tension in St. Petersburg. Massive snowstorms kept protesting workers at home and out of the streets, providing the illusion of calm in the capital city. But the weather also prevented rail traffic from entering St. Petersburg, as badly need food supplies and heating fuel were held up on snow-drenched tracks. A starving and freezing populace soon took to the streets in record numbers to protest their living conditions and the war.

250,000 protesters walked off their jobs on March 10th, 1917, effectively ending any industrial production. The move sparked panic in the Duma as the body’s Chairman, Mikhail Rodzianko, telegraphed the Tsar with his “anarchy” comment while desperately trying to convince the Tsar’s ministers to resign as a good faith effort to show that the government was listening to the people’s demands. Instead, the Tsar ordered soldiers to open fire on the crowd. Nicholas II had made similar orders before. His order in 1905 had killed or wounded hundreds in what was remembered as “Bloody Sunday,” launching what would become the 1905 Revolution. Nicholas II’s 1917 order would have a similar effect with a far worse outcome for his reign.

The men of the Fourth Company of the Pavlovski Replacement Regiment had heard of the clashes between other units of their regiment and protesters. The Fourth was determined to join the fight – on the other side.

The Fourth Company left their barracks and began opening fire on St. Petersburg police. While the Company would be quickly disarmed by fellow soldiers, the incident carried troubling implications as it was the first insistence of federal troops in open mutiny. News would filter around the city that even the loyalist Cossacks were becoming hesitant to carry out orders to attack unarmed civilians.

As the Tsar’s military was backing off from supporting him, the Duma was going one step further to revolution. Aided by prominent St. Petersburg bankers, Mikhail Rodzianko formed a Provisional Committee of the State Duma which promptly ordered the arrest of all current and former ministers of the Tsarist regime. In response, the Tsar ordered the dissolution of the Duma. It did nothing to quell the rebellion.

By March 12th, 1917, St. Petersburg was entirely in the hands of rebelling forces. Many Duma members now formed a Provisional Government and declared the body as the ruling authority in Russia. At best for the Tsar, a handful of military units declared themselves “neutral” in the revolution, preferring to stay in their barracks to following orders from either Nicholas II or the new government. Another 160,000 federal soldiers had chosen the Provisional Government, occupying the capital.

Even the royalist factions of St. Petersburg had joined the protests. A number of Dukes implored the Tsar and Tsarina to sign a “Grand Manifesto” declaring the re-establishment of the Constitutional system Nicholas II had promised in order to end the 1905 Revolution. Prince Georgy Lvov and Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich Romanov both submitted to the new government, with Lvov leading the new body as chair by March 16th, 1917 as a compromise candidate.

Within days, the entire base of Tsarist Russia’s power structure had crumbled with only modest pressure.

With the success of the “February Revolution” (named as such because the early events occurred in February by the old Russian calendar), it was clear that Nicholas II no longer held power. The real question was who did?

Nicholas II had abdicated, leaving his son Alexei as the current ruler of the nation. Not even 12 years of age, and a hemophiliac, Alexei would have been a poor choice to lead in such a fractured empire. After realizing that the current political winds would have likely forced him to be away from his son, and that Alexei’s health would have problems coping with the strain of rule, Nicholas II changed his mind by the next day, selecting his younger brother Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to rule instead. Michael had almost no popular support in Russia – indeed, he had taken a married lover and moved abroad in 1912 in the hopes of being removed from the line of succession altogether. It was a surprise to few that Michael declined the title.

The Provisional Government may have had the participation of the many of the former members of the Duma, but the practical power was in the hands of the Petrograd Soviet (“worker’s council”). The Soviet held the support of the striking workers and many of the rebelling soldiers, but it lacked the political infrastructure, or credibility beyond St. Petersburg, to rule effectively. Orders from the Provisional Government would now have to be run by the Soviet before being enacted, a point made clearly by the Soviet’s Order Number 1 – “The orders of the Military Commission of the State Duma…shall be executed only in such cases as do not conflict with the orders and resolution of the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.” The Provisional Government was being undermined only days into its existence.

But the Provisional Government would likely undermine itself within its first weeks by its pronouncement that the new government stay in the Great War, seeing the fight through to “its glorious conclusion,” in the words of the new Minister of Foreign Affairs. Thousands took to the streets to protest the government’s continued participation in a conflict that had taken so much for so little in return. The protests would be a worrisome portend of things to come, as the military commanders of St. Petersburg asked for permission to open fire on the protesters. The cycle of revolution was starting anew.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.