Despite the potential dangers of touring a front-line trench, Winston Churchill had more reasons to be grateful for his early-morning assignment. Gallipoli had tarnished his once promising political career, forcing the one-time First Lord of the Admiralty and key war-time cabinet member to a parliamentary backbencher with little voice in the conduct of the war. Churchill had decided instead to join the Army, being given the command of the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front. The unit saw little action, doing nothing for Churchill’s standing.

Only the fall of Prime Minister H.H. Asquith’s government gave Churchill a second chance. David Lloyd George invited Churchill back into the good graces of the war council, even giving Churchill the Ministry of Munitions – the same role that George had rode to fame, rescuing his own once morbid political career. As the Minister of Munitions, Churchill was touring near the meeting point of the British and French line; a position that had been in flux as the French dealt with mutiny and the British struggled to assume responsibility for more sectors of the Western Front. British units were at half their paper strength in this area and morale had been badly shaken by the course of the war on other battlefields. In the dark of the morning of March 21st, 1918, Churchill described what he heard:

“And then, exactly as a pianist runs his hands across the keyboard from treble to bass, there rose in less than one minute the most tremendous cannonade I shall ever hear…the enormous explosions of the shells upon our trenches seemed almost to touch each other, with hardly an interval in space or time…The weight and intensity of the bombardment surpassed anything which anyone had ever known before.”

3.5 million German shells rained down over the next five hours. The opening phase of the Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle) had begun. It would be the first of four separate offensives that would usher in the end of the Great War, and provide previews of the future horrors of the next world war.

German soldiers await their advance from their trench – despite the significant ground gained by the Germans in their Spring Offensive, they also suffered tremendous casualties

While the planning of Germany’s spring offensive had been haphazard and far from discrete (the British had known a major attack would be launched against them weeks in advance), the initial strike was nearly strategically and tactically brilliant in it’s execution.

The Arras–St. Quentin region was the dividing region between British and French control and with inter-Allied cooperation strained as the French followed Pétain’s strategy of “waiting for the tanks and the Americans” and the British vainly continued throwing themselves at the German line, responsibility for defending the sector was often unclear. Against the advice of his generals, David Lloyd George had accepted increased responsibility for the occupation of the region. The trench system at Arras–St. Quentin had gone through severe neglect and the need to hold more of the front had stretched British units beyond their capacity. Battalions that were suppose to hold 1,000 men now held 500 or fewer, meaning that the 26 British divisions in the region were in some cases at half their reported strength.

Roaring down on those divisions on March 21st, 1918 were 44 German divisions, 30 of which were comprised of elite Stoßtruppen. Thousands of artillery pieces, hundreds of bombing aircraft and a variety of poison gases flooded the front while stormtroopers pierced the line, overrunning British soldiers. The collapse at the front had been total. The initial goal of Erich Ludendorff’s planning back in the fall of 1917 – to divide the British and French armies and then press the British against the coast, forcing them to retreat back across the Channel – looked attainable. As German troops exploited the gaps in the Western Front, the Allies argued over who was suppose to reinforce and block the German advance before they arrived at the approaches to the Channel ports of Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk. British General Douglas Haig said he lacked the men to replace those who had been killed or surrendered. Pétain sent six divisions but was unwilling or unable to commit more.

Soldiers go “over the top” during the German offensive

Neither the British nor the French stopped the initial offensive – Germany simply overran it’s ability to resupply their men. Casualties had been heavy on both sides and the Germans had lost veterans they could ill afford to replace. But Germany sat within only 15 miles of the Channel in some areas. As the offensive renewed in early April, Haig spoke for many in the British command about the seriousness of the Allied position as he addressed the entire British Expeditionary Force by communique: “With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight on to the end.”

Just days into the German spring offensive, the city of Paris could be considered anxious but otherwise calm. The German action was targeting the British, not the French, and aiming away from Paris. Save for two zeppelin attacks earlier in the war, Paris had been relatively unscathed. That would change at 7:18 in the morning on March 23rd as a gigantic explosion could be heard echoing across the city. And then another. And another. Every 15 minutes an explosion rocked the French capitol, with nary a German plane or zeppelin to be seen. The French authorities couldn’t understand what was happening. But as they examined the bomb craters it soon became obvious – Paris was being shelled.

75 miles away from the City of Lights, the Kaiser Wilhelm Geschütz or more commonly known as “Paris Gun” was launching 234-pound shells into the stratosphere. For the first time in history, gunners were having to take into consideration the rotation of the Earth when coordinating their attacks. It would be part and parcel of the German offensive to attack the depleted morale of the French with such terror tactics, and morph into an otherwise misguided attempt to take Paris itself.

The “Paris Gun” – the largest gun in the world. It took only three minutes for the gun’s shells to reach the city

In the immediate aftermath of the first shelling of Paris, the American ambassador had confidently written to Secretary of State Robert Lancing that the attack had “only serve[d] to strengthen the resolve of the French to resist, to the last man if necessary, the invasion of such a foe.” In reality, the French had to ban ticket sales out of the capitol to prevent further fleeing as thousands escaped.

Ludendorff and the German General Staff likely knew little of this as they planned the next phase of their grand offensive. Despite having made significant gains against the British, to the point of legitimately threatening the BEF’s ability to stay in France, Ludendorff oddly chose to focus against the French for the next offensive. Believing that progress towards Paris would force the Allies to draw further men away the Channel region and northern France, German troops attacked the French Sixth Army. Having nearly depleted his core of stormtroopers and veterans, Ludendorff was lucky that the French Sixth had not deployed their men in a “defense in depth” strategy as most armies had begun to do to prevent being overrun in an initial assault. 50,000 Allied troops and over 800 artillery pieces were easily captured, including some Allied generals. Success spoiled any restraint that Ludendorff may have had for the operation and now suddenly the German General changed his mind – the offensive would attempt to capture the French capitol.

The offensive had opened up a dangerous salient that threatened the flanks of any future German attack but Paris was now only 35 miles away. Panic had gripped the citizenry and even the French government began hurriedly packing to abandon the city before the Germans could take it. For a moment, it appeared as though the Franco-Prussian War was about to be reenacted, with German troops seizing the French capitol and ending the war in one swift stroke. The heady days of 1914 and the war of maneuver had seemingly returned to the Western Front.

A crater from the “Paris Gun”

It was not to be. As expected, the Allies hit the German attack at it’s flanks and exhausted German soldiers, with many of their best and most experienced troops now killed, wounded or otherwise physically unable to fight, simply could not continue. Losses of hundreds of thousands of men piled up on both sides. Having lost his focus with the attack against Paris, Ludendorff would double-down with yet another offensive against the French line. Germany would gain nine more miles, albeit not directly towards Paris, at the cost of what little operational effectiveness the military had left.

As the Germans switched their primary focus to the French, the British were desperately trying to block any further advance towards the Channel.

At the city of Amiens, the British drew their line in the sand. A key rail and road junction in northern France, whoever held Amiens could pivot their forces across the region. The British had denied the Germans at the approaches to Amiens earlier at Villers-Bretonneux and were mounting a counteroffensive to be lead by a dozen Mark IV tanks. The Germans had prioritized taking Villers-Bretonneux as well, bring 13 of their own A7V tanks. The first tank-versus-tank duel in history was about to unfold.

A knocked out German A7V. The Germans attempted to destroy any of their unusable tanks to prevent them from falling into Allied hands

The result was fairly anti-climatic. Many of the tanks brought to the battle simply broke down from standard usage. The sheer size of both designs made traversing anything other than strictly flat ground dangerous to either tipping over or burning out the engines trying to climb even the lightest hills. Both the Mark IV and the A7V were Great War equivalents of heavy tanks, designed as much for intimidation as anti-infantry vehicles. While both tanks carried a 5.7 and a 6 pound main gun, it was the use of machine guns and the tank’s heavy armor that were relied upon in a fight. They weren’t designed to attack other tanks, at least not yet. But as three Mark IVs and three A7Vs engaged each other on April 23rd and 24th, the British Mark IVs won the day, officially destroying one of the A7V with his main gun as the other two retreated. The battle may have been won as much by accident as by effort, as some reports suggest the A7V actually fell over, exposing more vulnerable parts of the tank to enemy fire.

Regardless of the reasons, the British won the day at Villers-Bretonneux again, and the German drive for the coast had been halted.

By July, the last gasps of the Kaiserschlacht had been drawn. In terms of miles won or casualties inflicted, Germany had won a significant battle. Germany was closer to the English Channel or Paris than they had ever been and had caused over 863,000 Allied casualties. But the goal had not been to merely improve their position – it had been to force the Allies to the negotiating table. And by that metric, the offensive had been an appalling disaster.

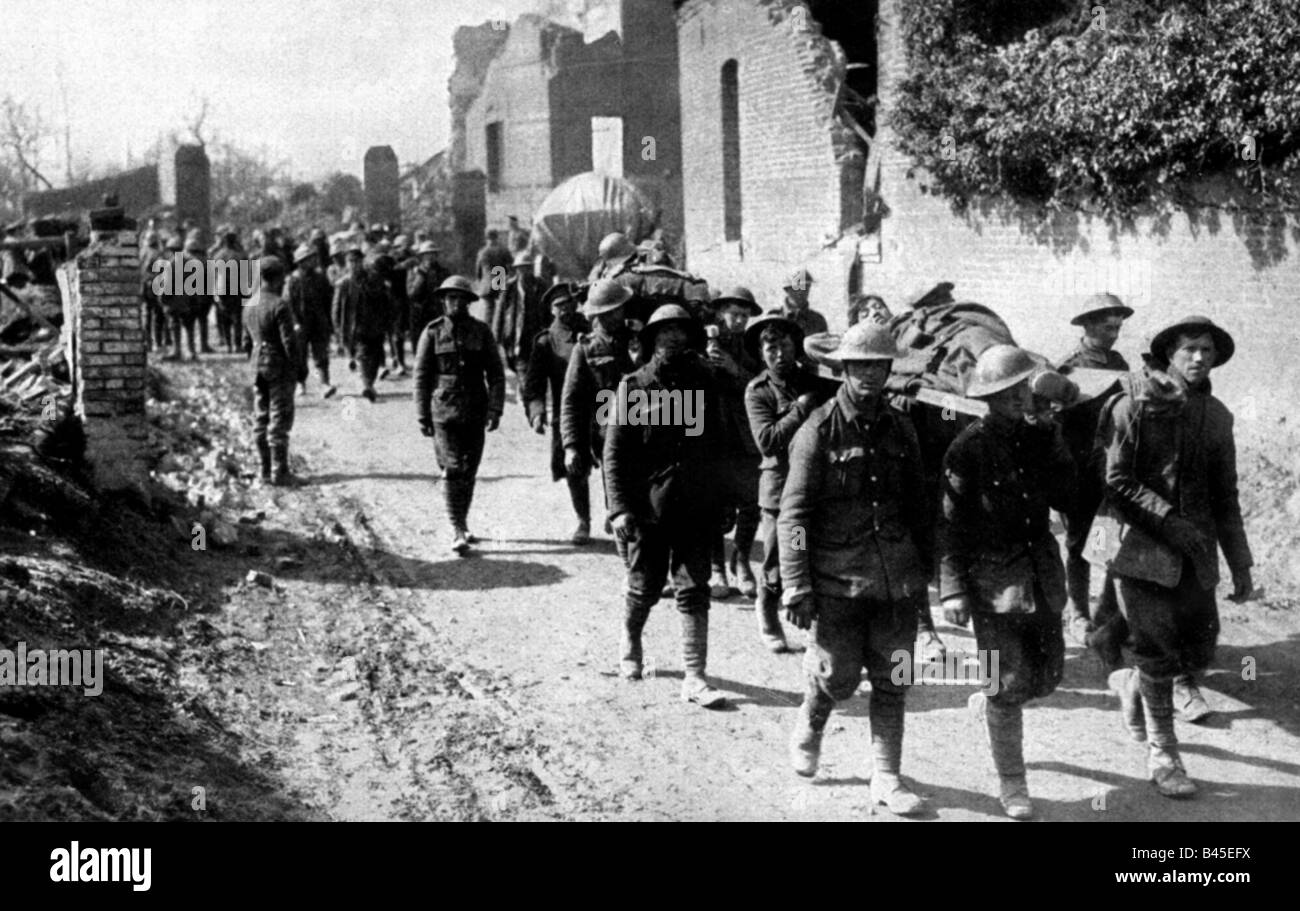

British soldiers back on the march – the forthcoming Allied response to the German Spring Offensive would usher in the death blow to Imperial Germany

In six months, the Germans had lost nearly one million soldiers as either casualties, prisoners or to other aliments. The cream of their army, the Stoßtruppen, was effectively gone. The morale of what armed forces remained, initially euphoric with the first victories of the offensive, had been ground to dust with months of constant fighting. And now the army was holding outstretched positions they could ill-afford to keep. The coming Allied counteroffensive would undo all of these gains and more.

On the other side of the trench emerged an Allied army weary and bloodied but now more unified than ever before. The issues of inter-allied command that had reached a head with the German offensive would now be resolved with the appointment of a Supreme Allied Commander – French General Ferdinand Foch. Foch had been partially credited with stopping the original 1914 German offensive at the Marne and since then had languished on the Italian front after a series of unsuccessful French attacks in 1915 and 1916. But Foch had been well regarded by commanders throughout the Allies and his professor-like demeanor seemed a welcome change from the dramatics of men like Robert Nivelle who overpromised and undelivered. By August, an estimated one million American soldiers would be in France and the advantage in manpower, to say nothing of morale, would now clearly pass to the Allies.

Germany still possessed large tracts of French and Belgian soil and a newly-won Eastern empire, but the foundation for the last acts of the Great War had now been laid.

It’s really amazing just how much stupid there was among the elites in Europe back then. From Ludendorff to Haig, the Kaiser, his cousin Nicky, the creator of the French tactic of elan to “overwhelm” machine guns, the creator(s) of the multi-million shell bombardments (and those who kept that flame alive) in spite of lacking any proven utility), and, of course, the Viennese idiots who started the whole spectacle.

jdm, elite does not equate to smart, intelligent or wise, just that they think they are better than everyone else. Please note, they think, not that they are. Just like the elite here. And for eons, peeons have been letting them get away with it. Shame on peeons!

Pingback: In The Mailbox: 06.01.21 (Evening Edition) : The Other McCain

It strikes me that generals are always fighting the last war, but at this point, we have the issue that those making decisions in Germany were becoming increasingly aware that if they didn’t pull a rabbit out of their hats and win it quickly, they would be commoners and cut off from their earlier lives of immense pleasure. They were watching exactly that happen in Russia–where ironically the Germans had helped send Lenin back on the Aurora. Desperate times, desperate measures, who the H*** cares if it makes a couple million more widows, I guess.

generals are always fighting the last war

A grand assertion with a lot to back it up. I agree. One of my points was that the sheer number of casualties, even in the first couple years of WWI, were so obscenely great that anyone not completely stupid would’ve, should’ve re-thought those tactics. It occurred to me that using millions of shells to puncture a line would make it very difficult for the supply units to catch up to the leading forces because the ground would be so chewed up as well as dangerous (not all shells explode when they’re supposed to).

jdm, agreed, and that brings up the second reality. If we introduce the thought that aristocrats know that they would become commoners or dead if the scope of their incompetence were known, then any number of actions to preserve their position become “reasonable”. Well, at least to them.

Pingback: All These Worlds Are Yours, Except Mitteleuropa | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: The Free Lord | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: The Black Day | Shot in the Dark