While Germany was hitting the Western Allies with hundreds of thousands of men and millions of rounds of artillery, their Austro-Hungarian ally was launching a far less impactful volley of words in the heart of their own nation. Austrian Foreign Minister Count Ottokar von Czernin had arrived at the Vienna City Council on April 2nd, 1918 to attempt to give an inspirational speech and rally the falling support of the Habsburg’s polyglot empire.

Czernin’s stemwinder specifically attacked France’s new Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau, as the major obstacle to peace with the Allies. Clemenceau had certainly drawn a hardline in the wake of the mutinies of 1917, stating that France’s policy would be “la guerre jusqu’au bout” (war until the end), echoing Britain’s David Lloyd George commitment to nothing less than total victory. But Czernin’s attack wasn’t merely personal but also proclaimed that Clemenceau’s boasts didn’t reflect the true will of France because the prior administration had reached out to the Dual Monarchy in an attempt to sue for peace the year before.

An outraged Clemenceau quickly revealed the truth – it had been Austria-Hungary which had attempted to make a separate peace in early 1917. And the proof came in the form of letters and communications from none other than the newly crowned Emperor himself, Charles I.

Karl Franz Joseph Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Maria had never intended to become the Emperor of the Dual Monarchy. At his birth, he was the great-nephew of Karl Joseph and quite a distance removed from any realistic considerations towards obtaining the crown. Karl studied science at a public school and then politics and law during his service in the army, becoming more of an educational dilettante than a man dedicated to any particular field. HIs years of work had won him few accolades but neither had he acquired any detractors. In some ways, Karl was a model member of the royal family – dutiful, friendly, family-oriented and deeply religious.

As Karl went through the motions of his education and service, the list of heirs before him became shorter and shorter. Franz Joseph’s only son, the Crown Prince Rudolph, killed himself in a suicide pact with his mistress. The Emperor’s elderly brother became the next in line, until he died from typhoid. And then with the assassination of the Emperor’s nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Karl found himself directly in line to succeed the aging Austro-Hungarian monarch. Franz Joseph had done little to prepare Karl for the responsibilities of leadership when he died in the fall of 1916 and the affable, if unremarkable, Karl was now Charles I (or Karl I, depending on which is his many official titles one wants to go by).

The Empire that Charles I inherited already appeared on the brink of internal collapse. Like Germany, Austra-Hungary saw their food production decline with their wheat output being cut more than in half by 1917. Unlike Germany, the Austro-Hungarians had counted on a great amount of food imports from Russia and Romania in the pre-war years, meaning the populace’s starvation came on even faster. And while the political divisions of an empire comprised of so many ethnic groups each wanting increased autonomy, if not independence, was well-known even then, the core power-sharing structure between Austria and Hungary was rapidly fraying as well.

The Hungarians had not dissolved their parliament, as had the Austrians on the eve of the war. As a result, the Hungarians began wielding greater independent political power as Franz Joseph struggled keep the empire unified. The Hungarians had gone as far to close their border to Austria – preventing travel and trade. The Hungarians refused to trade food stuffs to Austria, even pointedly trading food with Germany instead of their own Imperial partner. Fuming Austrians vented their political angst when Charles I allowed the Austrian parliament to reconvene, with ethnic minorities immediately declaring in May of 1917 that “a democratic Europe…of autonomous states” should be the goal of the war effort, not the continuation of the Habsburg empire. Seemingly no one in the Dual Monarchy wanted to stay together.

Charles I attempted to wield both carrots and sticks in an effort to keep the empire unified. The potential of a third crown in the Empire, this one given either to Croatian or Slavs in general, would dilute the relative power of Austria and Hungary and empower the minorities who were being courted to join a Yugoslavian alliance. With the renewal of the Austro-Hungarian pact due, Charles I had to toe a difficult line – he couldn’t let the Hungarians (or others) run roughshod over him, nor could he appear as too uncompromising and risk the Dual Monarchy becoming a singular crown. Fortunately for Charles I, most of the current political leadership of the empire was associated with the horrendous war effort, allowing the new monarch to sack both liberal revolutionaries like the Hungarian Prime Minister, Ivan Tisza, who preached total independence from Vienna, and old-guard conservatives like Chief of Staff Conrad von Hotzendorff, who opposed Charles I’s efforts at constitutional reform.

These early moves won Charles I – and the empire – a relative stay of execution as the Hungarians renewed the alliance…for two more years, instead of the proposed twenty. The renewal was followed by munities from several different ethnic groups within the army. By the spring of 1917, Charles I saw the writing on the wall – Austria-Hungary had to end the war or risk permanent dissolution.

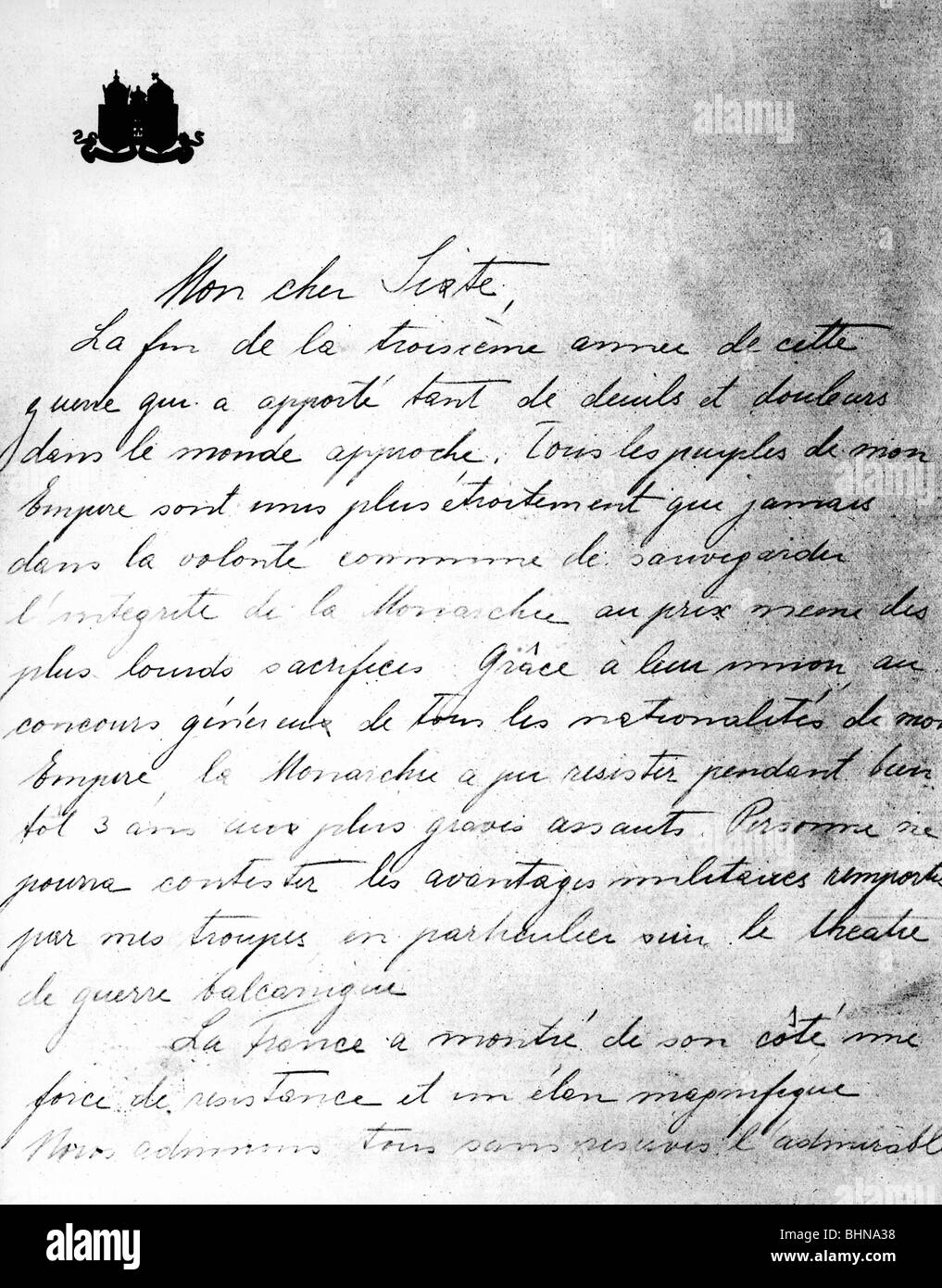

But how could Chares I contact the Allies without risking German reprisals? Charles I had few allies within the country and likely even fewer contacts outside of it, having risen to the role as heir apparent so recently. The potential solution came from his wife’s family. Empress Zita, Charles’ wife, could count Italian, Austrian, Swiss and Portuguese heritages and spoke six languages herself. Her brother, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, was technically Italian royalty and yet served in the Belgian army as an officer. Writing her brother, Zita invited Sixtus to Vienna via Switzerland to help conduct negotiations.

Sixtus’ arrival wasn’t merely obscure royalty play-acting at diplomacy. The Italian Prince had been in contact with both the French and British before his departure and came armed with a list of Allied demands for even starting peace talks: France would get Alsace-Lorraine back; both Belgian and Serbian independence would be guaranteed; the Italians would get Tyrol and the Russians would receive Constantinople. On paper, these seemed like demands designed to ensure negotiations would be a non-starter. How Charles I was suppose to convince his nominal allies to surrender core territory and essentially accept an Allied victory is simply unknown. Nevertheless, Charles I agreed to the terms, stating in the letter he returned with his brother-in-law that “I will use all means and all my personal influence” to realize the Allied demands.

What followed was…nothing. Some version of the Allied pre-conditions were passed along to Germany, although the context of how or why Charles I had come into contact with them is unknown. With the tide of war favoring the Germans throughout 1917, the Allied terms seemed more and more unreasonable. No further communication followed and despite the potentially humiliating letter from Charles I, the Allies sat on the evidence until Czernin’s speech. Whatever rationalizations or narrative Charles I had told his German allies in 1917 had apparently been false as the letter clearly showed that Charles I had invited the negotiations and was willing to accept the punitive Allied terms. Germany’s biggest ally had sought a way out of the war by themselves.

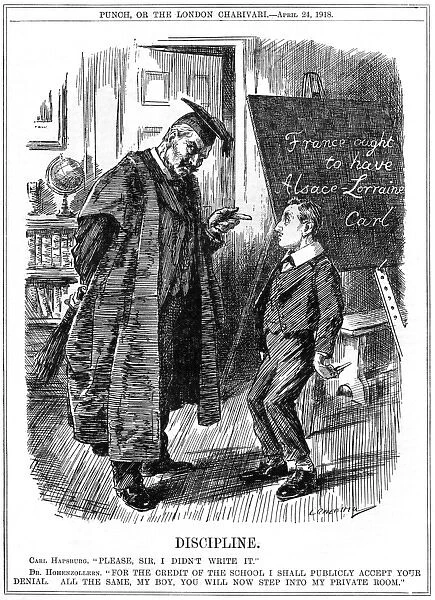

News of the “Sixtus Affair” briefly gripped Europe. Rumors spread that Germany might invade and occupy their Austrian ally or that Charles I might even abdicate. Indeed, Czernin attempted to convince Charles I to do precisely that in an attempt to placate the Germans. Unwilling to throw the dying Dual Monarchy into further chaos, Charles I accepted Czernin’s alternative – making a public “Word of Honor” pledge essentially denying the most explosive charges from the released letter and recommitting to the war effort. Charles I would also travel to Spa, Belgium, where the Kaiser was located to oversee the war effort, to publicly and privately apologize. For the Germans, words were far from enough. Charles I and the Dual Monarchy would have to accept Germany’s post-war vision for Europe – Mitteleuropa.

The brainchild of German thinker Friedrich Naumann in 1915 from his book of the same name, Mitteleuropa was a Prussian vision of a German-dominated Europe. But Mitteleuropa was far less Mein Kampf and much more a Germanic European Union in which trade and economic policies were dictated in Berlin. Given Germany’s economic dominance in continental Europe, in some cases Mitteleuropa could appear as little more than a statement of geopolitical fact – that Germany was the dominant power in central and eastern Europe and could dictate regional economic policies by virtue of that dominance. Indeed, the structure of such a plan had already been introduced by Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg as part of his proposed “Central European Economic Union” in 1914, a concept that would evolve to even including France as part of a larger unified customs programme that would aid inter-European trade. One can easily see the outlines of the European Union and Germany’s 21st Century economic policy dominance within Mitteleuropa and similarly inspired concepts.

But Mitteleuropa would not merely be a statement of German economic influence. It would involve cultural and political control as Germany sought to literally define new states in Eastern Europe that they could view as little more than vassals. Ukraine, the Baltics, Finland, Romania and a planned Tatar Republic in the Crimea would all be essentially German colonial states. And with part of the Mitteleuropa plan being the empowerment of Hungarian rights and claims, Charles I’s public and private acceptance meant the eventual dissolution of the Dual Monarchy, albeit one managed under German control. Vienna had already had it’s military policy dictated from Berlin due to their failings on the battlefield. Now, Charles I had forced the empire into a planned obsolescence, making Austria another future German puppet.

Humiliated internationally, Charles I vainly attempted to strengthen his hand at home, reconvening the Imperial Parliament in the wake of the Sixtus Affair. Charles I had hoped to at least get agreement upon a new confederation that might replace the Dual Monarchy, with each member state holding greater autonomy. But the moment for any such reconciliation had passed – the Imperial Parliament’s minorities would settle for nothing less than full independence. Although the war had many months to go, Charles I now knew the Dual Monarchy would be finished – the only question was whether it would be dissolved by the Allies, the Germans, or themselves.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.