In September of 1914, at the very outset of the Great War, a dreadful rumor arose. It was said that at the Battle of the Marne, east of Paris, soldiers on the front line had been discovered standing at their posts in all the dutiful military postures – but not alive. “Every normal attitude of life was imitated by these dead men,” according to the patriotic serial The Times History of the War, published in 1916. “The illusion was so complete that often the living would speak to the dead before they realized the true state of affairs.”

It was blamed on asphyxia, the result of such powerful new high-explosive shells fired at massive intervals – 432,000 shells had been fired in 5 days at the Marne. That such an outlandish story could gain credence was not surprising: notwithstanding the massive cannon fire of previous ages, and even automatic weaponry unveiled in the American Civil War, nothing like this thunderous new artillery firepower had been seen before. The rumor emanating from the Marne reflected the instinctive dread aroused by such monstrous innovation.

Only the “frozen” men at the Marne were not actually dead. Rather, what the survivors of the first days of the Great War were experiencing and witnessing was an issue that would dominate every major army for the next four years – shell shock.

—

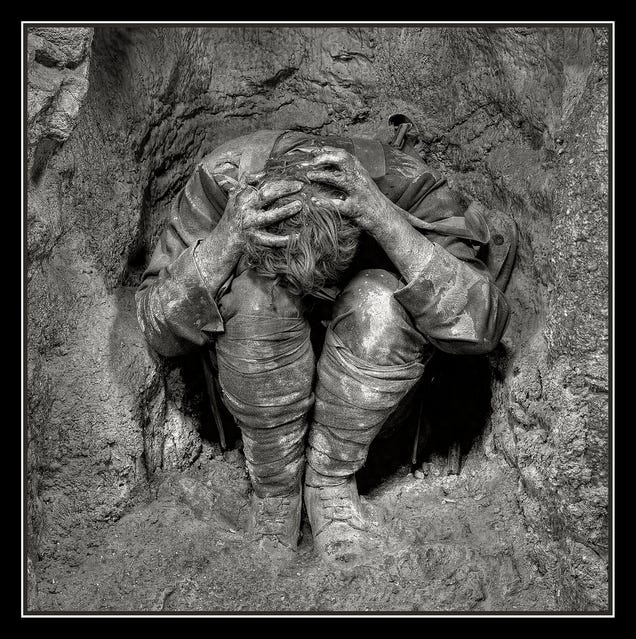

Duck & Cover – the scale of warfare experienced by the men in the trenches was unlike anything any army had encountered before. No army was prepared for how a largely conscripted, civilian-based military would react

“Shell shock,” the term that would come to define the phenomenon, first appeared in the British medical journal The Lancet in February 1915, only six months after the commencement of the war. In a landmark article, Capt. Charles Myers of the Royal Army Medical Corps noted “the remarkably close similarity” of symptoms in soldiers who had been exposed to exploding shells. The first cases Myers described exhibited a range of perceptual abnormalities, such as loss of or impaired hearing, sight and sensation, along with other common physical symptoms, such as tremor, loss of balance, headache and fatigue.

Early medical opinion took the view that the damage was “commotional,” or related to the severe concussive motion of the shaken brain in the soldier’s skull. Shell shock was initially deemed to be an entirely physical injury, and the shell-shocked soldier was thus entitled to a distinguishing “wound stripe” for his uniform, and to possible discharge and a war pension. Myers disagreed with the burgeoning conventional wisdom, concluding that those suffering from “shell shock” were psychological rather than physical casualties, and believed that the symptoms were overt manifestations of repressed trauma.

The distant stare of the man on the far left epitomized the public view of a shell-shocked man. For most of the armies, for large parts of the war, such reactions were deemed physically, not emotionally, based

The recognition of what we now would call post-traumatic stress disorder (or PTSD), would save lives – but not without a long fight.

—

As the strain of life in the trenches was pushing all the combatants to try and keep their soldiers under command, most armies began to see shell shock as nothing more than cowardice or an overall lack of discipline.

The British Army alone prosecuted 240,000 court-martial cases for actions that likely reflected shell-shocked men overwhelmed by the industrialized butchery of the Great War. Over 3,000 of those men were sentenced to death, with all but 346 having the sentence commuted. Similar punishments were handed down by the French and German armies for their men, with 700 French troops executed for “cowardice” and only 48 Germans.

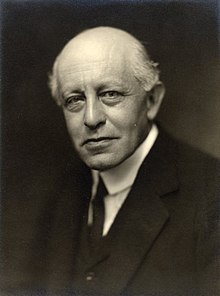

Dr. Charles Myers – having been denied an officer’s commission due to his age (42), Myers essentially snuck into France to treat men and was rewarded with a rank later

Myers would be criticized by those in the military who thought the condition would be better addressed by military discipline; dismissing that shell-shocked soldiers had any real illness. Often men believed to be shell-shocked would be forced to stay in the front lines after their units had been transferred to a position in the rear of the line as punishment.

Military-approved medical treatments were often even worse. Dr. Clovis Vincent of the French Army provided an apparent solution with his use of torpillage or ‘torpedoing’. This involved using electro-convulsive treatments. Lewis Yealland in London used a similar treatment regime. ‘Faradization’, the application of electric shocks to the affected parts of a soldiers’ body (the tongue if the patient could not speak or the arm if he was paralyzed, for example), produced results that could be called a success, if a simple return of sensation or speech was a cure.

346 British soldiers were executed during the Great War, most of them for actions revolving around “shell shock” or related battlefield psychological trauma. The French executed over 700 men for the same reasons

The German Army seemingly handled the issue of what to do with the shell-shocked men better than their Entente opponents. While German doctors followed early British and French medical practices of electroshock therapy (Überrumpelingsbehandling), they also abandoned such practices faster. More worried about the overall morale of the Army than the morale of one solider, Germany was more willing to transfer shell-shocked soldiers out of action and into counseling or similar therapies. Men too emotionally damaged to fight would be not be discharged but given Home Front duties in hopes of transitioning them back to normal life.

Such policies did not yet exist in the British Army in the summer of 1915.

—

A exhausted French soldier. If the British eventually realized they couldn’t shoot their way into greater discipline, the French never abandoned martial punishment as the primary means to combat shell-shock

If the British Army was willing to shoot shell-shocked men, and British doctors were willing to essentially electrocute them until “healthy”, Dr. Charles Myers was determined to try and actually cure those suffering from the effects of the Front.

Myers proposed a system by which doctors would refer severe cases of shell shock directly from the base hospitals in France to specialist treatment centers in Britain. He argued that effective treatment required individual attention, which in turn demanded higher staffing ratios – ideally one doctor to 50 patients. To meet this demand, he persuaded the War Office to set up training courses in the principles and practice of military psychiatry and, in particular, the treatment of shell shock.

Along with William McDougall, another psychologist with a medical background, Myers argued that shell shock could be cured through cognitive and eventual reintegration. The shell-shocked soldier had attempted to manage a traumatic experience by repressing or splitting off any memory of a traumatic event. Symptoms, such as tremor or contracture, were the product of an unconscious process designed to maintain the dissociation. Myers and McDougall believed a patient could only be cured if his memory were revived and integrated within his consciousness, a process that might require a number of sessions.

Faradization – the practice of delivering electroshock therapy for shell-shocked men brought widespread public outcry once it was discovered. Had Dr. Clovis Vincent not been violently attacked and injured by one of his patients, the practice might have continued

Myers and McDougall’s work was allowed to proceed, but with only the most tepid support from the British authorities. Despite a growing conscious that shell-shocked men were suffering psychological, not physical, injuries, the British government continued to refuse to acknowledge the role stress was playing on their soldiers. After the war, the term “shell-shock” was banned by the British Army in favor of “post-concussional syndrome” – a term implying that the injuries were something a bandage and bed-rest could cure.

The difference upon returning home was palpable. Men discharged for shell-shock would not only be ostracized, but be stripped of any military pension. A generation of men would come home emotionally broken to find themselves financially broke as well.

—

Myers’ research and conclusions didn’t find favor even after the war.

In 1940, Myers wrote his memoirs, detailing his theories about shell shock and its treatment to a new generation. The book was trashed by the military reviewer in the Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, who argued that Myers’s criticisms of the army’s medical services were unpatriotic and defeatist. It was little wonder then that Myers passed on participating on research projects between the wars.

Myers would get a measure of victory, in the end, as his treatment procedures would eventually be adopted by the Allied armies towards the end of the Second World War – a change far too late for thousands of men a world war earlier.

It wasn’t PTSD, it was brain injury. We are so in the dark ages, still. Even 10 years ago, doctors didn’t understand that the shock wave going through your brain can cause damage even when there is no external injury. Military research has also shown that the injury is multiplied when you have multiple blasts in quick succession. It is a physical injury with some psychological symptoms.

Reminds me of a man I saw when I went in for surgery as a kid–he looked normal until you saw the vacant stare on his face. My doctor informed me that he’d been wonderful with people until his car accident, and something…..changed. Can’t say whether it’s physical, mental, or a little of both (but that’s my guess), but man….

My grandmother (and namesake) was a psychiatric social worker at St. Elizabeth’s in DC. Whenever I hear about shell shock victims of WWI I think of her because from what I have been told that was her primary clientele. As for myself, I got a taste of what “battle fatigue” must be like when I was in Venezuela during a coup attempt. It only lasted a day but I was a mile away from an airbase that was being shot at from above and defended with anti-aircraft guns. The noise which echoed off skyscrapers was not only loud but pretty much random. I can’t imagine being right on top of it.

Pingback: The Strain | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: Cliffhanger | Shot in the Dark