The ship was already listing badly at 4:02pm when the order was given to abandon her on April 7th, 1945. Seven torpedo hits, and countless bombs, were the source of belching smoke and fire that could be seen for miles. The ship’s magazine stocks were engulfed in flame as well, reaching critical levels that might set off the ammunition. The cooling pumps, designed to douse such fires, had long since been broken in the battle.

By 4:05pm, the ship was sinking, listing so badly that when the final wave of American torpedo bombers attacked, they actually struck the bottom of the hull. The ship rolled completely to her side, her 70,000 tons shifting so dramatically that the ship’s forward magazines collided, setting off a massive explosion that was witnessed as far as 100 miles away. 3,055 of her 3,332 crew would join her at the bottom of the Pacific.

The largest battleship in history – the Yamato – was no more.

—

The Yamato in 1941 – along with her sister ship the Musashi and the German Bismarck – were the largest battleships that fought in World War II. All three would not survive the war

It could said that the Yamato was an anachronism by the time she first set sail in the fall of 1941. After all, nearly 12 months before the Yamato launched the British were proving at Torino that the aircraft would soon reign supreme at sea. But then, the Yamato was as much the product of political concerns as military ones.

The Washington Naval Treaty of the 1920s was the naval equivalent of the SALT talks in the late 1960s and 70s – a multilateral attempt at armament control. Concerned that the naval arms race between Britain and Germany had contributed to the Great War, and with the world’s three largest naval powers – Britain, the U.S. and Japan – eyeing one another warily, it was hoped that the Washington Naval Treaty would forestall future tensions.

Instead, the Treaty only increased tensions as it seemed to cement Britain and America’s naval predominance at the expense of Japan. Limits were placed on the culmatative weight of warships. And only British and American warships would be allowed to be the largest – with a limit of 525,000 tons total between capital ships (battleships, in essence). The Japanese would be capped at 315,000. Already knowing that such limits would be disregarded in the event of a war, and that British and American industry would eventually outpace Japan during a prolonged conflict, it made little sense for the Japanese to agree to a treaty that put them at a strategic disadvantage before a shot had even been fired.

The Yamato and Musashi in 1943. The Musashi would be sunk in 1944

By the time of the Second London Naval Treaty negotiations of 1936, the writing was on the wall. If Japan was going to expand and defend her territorial ambitions, she couldn’t be limited in her navy. Japan would need a navy capable of countering larger British and American fleets – of battleships that could duel with multiple rivals at once. The Japanese abandoned the Washington Treaty.

—

At 862 feet, 70,000 tons and with nine 18-inch deck guns (the largest ever installed on a warship), the Yamato was designed to match American naval quantity with Japanese quality. The first of two Yamato-class ships constructed by Japan (the Musashi would follow in 1942), the Yamato would provide a figurative and sometimes literal flagship for the entire Japanese Navy. The name had historic poetic ties to Japan itself and served as the lead ship of the Combined Fleet. Isoroku Yamamoto led the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor from the bridge of the Yamato.

The Yamato at Leyete Gulf – one of the few other times the Yamato saw action in World War II

For a battleship designed explicitly to engage multiple Allied warships at once, the Yamato saw surprisingly little action throughout most of the war.

Instead the Yamato soon developed a reputation as the “Hotel Yamato” among the cruiser and destroyer commanders in the South Pacific. Arriving at the critical Japanese base at Truk in August of 1942, the Yamato sat docked for almost an entire year, relegated to being the naval equivalent of a floor model – too nice and too expensive to risk damaging by ever using. It wouldn’t be until June of 1944 that the Yamato would see significant action.

Even if military tactics had already bypassed the Yamato, and even if the Japanese had invested too much to risk the Yamato sinking (she cost an estimated 250 million yen in 1940), the ship was most certainly a target to Allied forces.

Vice-Admiral Seiichi Ito – the last commander of the Yamato, Ito opposed the suicidal use of the ship…until informed that the Emperor expected the Navy to oppose the Okinawa invasion

At the battles of the Philippine Sea and Leyete Gulf, American bombers sought out the Yamato and her monstrously-sized sister Musashi (who had replaced the Yamato as the official flagship of the Combined Fleet), scoring hits on both vessels and finally claiming the Musashi on October 24th, 1944. In return, the Yamato saw her only surface combat of the entire war, engaging the “Taffy 3” American escort group, led by 6 escort-sized aircraft carriers. The Yamato scored a direct hit on the carrier Gambier Bay, damaging but not sinking her, before being driven off by a combination of destroyer-launched torpedoes and aircraft.

It was an inauspicious engagement for the supposed pride of the Japanese Navy.

—

The Yamato at Kure on March 19th, 1945 – despite her size, the Yamato’s speed (27 knots) allowed her to avoid any serious damage

As the Japanese Empire shrank, and the reach of American fighters and bombers expanded, there were fewer and fewer places where the Yamato could hide.

With the Japanese surface fleet reduced to a dozen capital ships and three small escort-sized aircraft carriers, any offensive naval action bordered on the suicidal. Worse, what remained of the fleet, especially the Yamato, was being constantly hunted even in friendly waters. On March 19th, 1945, 3 American aircraft carriers struck at Kure, the main Japanese naval base, in a sort of reverse Pearl Harbor. 16 ships in all were damaged, with the Yamato avoiding any direct hits.

Coupled with the American invasion of Okinawa on April 1st, the noose around what remained of the Japanese Navy was tightening. And it was clear that either the Yamato could be lost in battle or be possibly sunk at her moorings at some friendly base. With nearly 1,500 Japanese pilots sacrificing themselves in kamikaze attacks at Okinawa, a similar attack with the Yamato was conceived by the Navy. The Yamato, and a small escort fleet, would sail to Okinawa, engage the invading American forces, and then beach herself, using the ship as a giant gun position until she was destroyed.

Bowed but Not Broken (yet) – a photo taken from one of the attacking American planes shows the Yamato on fire

It was a suicidal gesture – and opposed by many members of the Navy.

Captain Atsushi Ōi, the head of the escort fleet division, was told that the operation was necessary for “the tradition and glory of the Navy.” He replied, “who cares about their glory? Damn fools!” The Yamato‘s commander, Vice-Admiral Seiichi Itō, didn’t wish to destroy his crew in a futile operation either. But an off-hand question by Emperor Hirohito during his briefing on Okinawa – he asked if the Navy had any operations in mind to defend the island – led to the impression that the Emperor approved wasting the Navy’s largest vessel in a last-ditch battle. That interpretation of one sentence was enough to overrule any objections and condemn the lives of 3,300 men.

—

Guarded by the light cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers, the Yamato left port on April 6th, 1945 to do battle with the Allied fleet of 1,300 ships. She was immediately spotted by American submarines and scout aircraft who shadowed Yamato for miles. Despite the size of the Allied fleet supplying and guarding the Okinawa invasion, there was legitimate concern about how much damage the Yamato could do if she managed to slip past the fleet’s surface and air screen. If the Yamato was turned loose against the supply convoys or the Allied fleet’s aircraft carriers, the invasion itself could be jeopardized.

Dōmo arigatō, Mr. Yamato – the final explosion of the Yamato (set off by the ship’s magazines), taking 3,055 of her 3,332 crew with her

The American 5th Fleet commander, Admiral Raymond Spruance, immediately ordered a task force to assemble to counter the Yamato. 6 older battleships, 7 heavy cruisers and 21 destroyers would strike the Yamato before she reached the heart of the fleet. For a moment, it looked like one of the largest surface naval battles since Jutland in World War I might occur.

It was not to be. Eight American aircraft carriers and 400 planes intervened on April 7th. The initial attacks were cautious – the Americans couldn’t believe the Yamato didn’t have some air cover lurking elsewhere; perhaps those 3 remaining small aircraft carriers were a distant part of the Japanese fleet. But by noon, it was apparent that the Japanese had left the Yamato to fend for herself. Waves of bombers hit the Yamato repeatedly; the ship’s 150 anti-aircraft guns unable to provide an adequate defense. The Yamato‘s companion vessels weren’t faring any better – the Yahagi and two destroyers had already been sunk.

The constant attacks finally robbed the Yamato of her once greatest asset – her speed. Slowed to 10 knots (from her maximum cruising speed of 27 knots), the Yamato couldn’t evade the attacks against her rudder that disabled her. Within 20 minutes of Vice-Admiral Ito’s order to abandon ship, the Yamato had rolled over and exploded, taking several American planes with her as shrapnel from the massive explosion flew into the air. 12 American airmen died for the loss of 4,250 Japanese aboard the several vessels sunk.

—

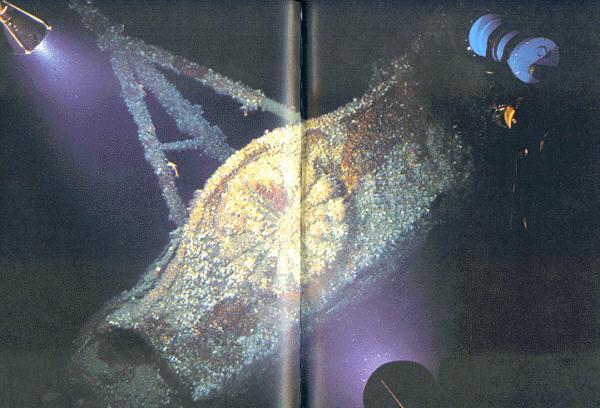

The Wreck of the Yamato – discovered in 1984, the ship had split into pieces and is scattered across the South China Sea

While the loss of the Yamato had real strategic importance – the Japanese never conducted another naval operation for the rest of the war – it had larger symbolic consequences. As one member of the Navy’s General Staff put it, the Musushi and Yamato were “symbols of naval power that provided to officers and men alike a profound sense of confidence in their navy.” Coupled with the Yamato‘s poetic allusion to Japan itself, it appeared that as the Yamato sank, Japan was metaphorically sinking alongside her.

Discussion of the Washington Naval Treaty isn’t complete without a mention of Herbert Yardley, who was breaking the Japanese codes, during the negotiations, and then later sold information about the code breaking to the Japanese, and then sold the same information to the Saturday Evening Post, and then published it as a book.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Yardley

**** That interpretation of one sentence was enough to overrule any objections and condemn the lives of 3,300 men. *****

And yet Hirohito claimed he had no real power. We don’t seem to be any closer to the truth of the matter.

It’s worth noting that Yamato wasn’t that fast–Bismarck and the Iowa class battleships were a clear 3-6 knots faster, not to mention what the cruisers and destroyers were capable of doing. It was competitive with 1930s battleships and before, but not with those laid down when they realized you had to be able to keep up with carriers. If you contrast the lines of Yamato with Iowa or Bismarck, the Japanese ship really resembles little so much as the Emma Maersk in comparison–and those cargo-ship-like lines don’t make it easy to accelerate.

So we might argue that the very thing that did distinguish the Yamato class–sheer size–also prevented them from being used, even had the Japanese wanted to risk them. They were simply too slow to catch up with U.S. task forces–many of which did not feature battleships because U.S. battleships prior to the Iowa class also couldn’t keep up with carriers.

BTS, in the middle of your writing, “fared”, not “faired.” (edit my comment once you correct if you like)

and HA–BTW, not “BTS”, typo on my part as I pointed one out. Poetic justice there. :^)

Noted and corrected, Bubba – good catch.

As for Yamato’s speed, I guess I was merely comparing her 27 knots to some of the smaller capital ships of the Japanese fleet, and then adjusting for her size. While battleships of the Kongo class were definitely much faster (30 knots), other classes like the Ise or Nagato were lucky to get close to 27 knots.

For a ship of her size, she was relatively fast. I should have provided more context to the remark, however.

Depends on how you define “size”–weight or length. If you look up other battleships laid down after 1937 or so with overall length of 800′ or more, it’s really interesting that (a) Yamato is slow in comparison, (b) it’s really underpowered (most ships half her tonnage had more horsepower), and (c) its range was pretty low compared to her peers–about half that of the Iowa class. Most battleships completed before 1937 were used mostly for shore bombardment for invasions, as far as I can tell, and probably for this very reason.

So all that extra steel made her able to fire 18″ guns without capsizing, but at the expense of speed and range, a Japanese Maginot Line as it were.

I love reading these. Just saying.

Pingback: The Feeding Frenzy | Shot in the Dark