It was seventy years ago today that the British Royal Navy brought the naval world into the 20th century – and gave the Imperial Japanese Navy a bright idea that would come back to haunt us.

First, a look back at some world and literary history. Then, some technology.

———-

For big nations in the 1500s through the 1940s, having a neighbor with a big, powerful navy was sort of like knowing one of your neighbors has a badly-trained pit bull and a hole in their fence; even if you don’t see the dog, you make sure all your barbecues are in the back yard; even if the enemy navy never comes out to gight, you have to keep in mind that they could, with dire results in lost ships and wrecked commerce and severed military lines of communication. This equation has dominated much of modern Western history; from King George’s ships of the line to the Great White Fleet to the Dreadnoughts to the entire NATO fleet of the fifties through the eighties (built to fight a Soviet submarine fleet that, thanks to Ronald Reagan, is now largely long-scrapped or rusting away at dockyards around Russia).

Of course, the daring admiral’s solution is to go to where the enemy fleet is holed up, and destroy it. That way, your nation doesn’t have to compensate for that big, unseen threat anymore. Sometimes it doesn’t work – Xerxes came to grief when he tried to root out the Greek fleet at Salamis, and got rooted out himself.

Sometimes it does; Duncan at Camperdown and Nelson at The Nile and Decatur’s sailors and Marines at Tripoli managed to change the fates of nations and the courses of wars by sailing not only into harm’s way, but into their enemies’ home ports to destroy them and render them moot as strategic factors.

In 1925, Hector Bywater’s novel The Great Pacific War described a fictional Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, with the intent of taking control of the western Pacific. The scenario involved a line of Japenese battleships steaming into Pearl Harbor by surprise and wreaking havoc.

Fanciful? Of course. Everyone knew you couldn’t sail a hostile battleship into Pearl Harbor!

Still, the idea of somebody destroying US naval power in the Pacific in a surprise coup de main was floating around. Implausible – Bywater was most likely called an “paranoid southern wingnut” by liberals of the day who were ignorant that he was the Times of London’s naval affairs corrrespondent – but it was out there.

We’ll come back to that.

———-

There have been few times in the history of warfare when technology advanced as fast as it did in the fifteen years between 1930 and 1945.

In 1930, the tank was a rattling, unreliable contraption assembled with rivets and armed with a popgun and almost as much danger to its own crew as to any enemy. Infantrymen carried bolt-action rifles not much different than the ones their fathers carried in 1900. Air forces were composed of biplanes that puttered along at 180 mph. And the world’s navies were largely dominated by battleships.

And when navies went to sea to duke it out, they found each other more or less the same way they had 130 years earlier, in the age of Nelson and Decatur – via the human eye.

Of course, the lookouts reported their findings to other ships via radio, which was edgy stuff even in 1930. And some of those lookouts flew in airplanes – floatplanes launched from battleships and cruisers and, in a few navies, launched from the world’s first aircraft carriers.

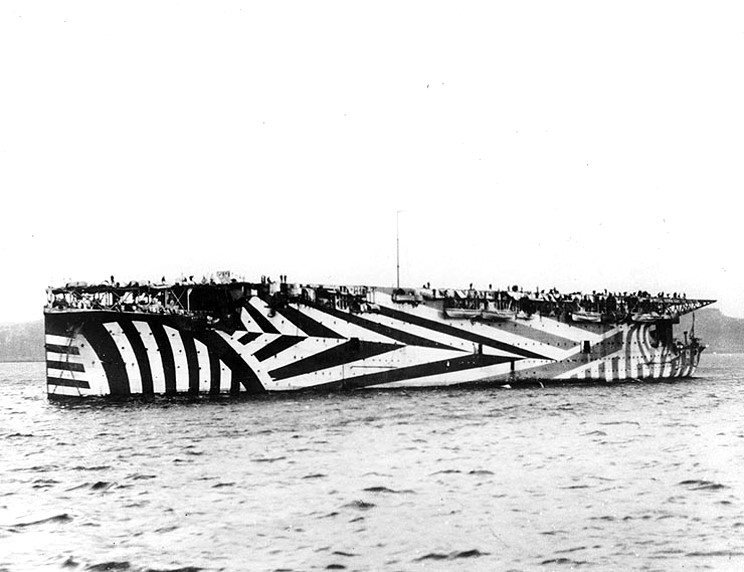

For all of its reputation for hidebound traditionmongering, the British Royal Navy led the world at seeing the utility of aircraft at sea. They built the world’s first seaplane carrier – the HMS Campania, in 1916, which launched float planes with crude bombs to attack the Zeppelin bases that were launching the air raids that were terrorizing London – and, in 1918, they converted a fast ocean liner into the world’s first flat-top aircraft carrier, the HMS Argus:

HMS Argus, the world’s first operational aircraft carrier, in 1918. The ship served throughout World War II.

HMS Argus, the world’s first operational aircraft carrier, in 1918. The ship served throughout World War II.They saw the role of the aircraft carrier to be not just scouting for the fleet and correcting the gunfire of the battleships, but attacking enemy ships. They developed the world’s first torpedo bombers – allowing a tiny, flimsy airplane made of doped canvas and wood and string to sink the most powerful battleship – in theory.

So as the technology to deliver an attack literally and figuratatively zoomed ahead, the technology to detect an incoming attack – the human eyeball – stayed more or less the same way it’d been for all of naval history.

Which meant that if a lookout on a ship saw aircraft coming in at twenty miles out, flying at the then-blistering pace of 120 mph (that was a fast torpedo plane indeed, in 1930), it gave ten minutes’ warning to get an aircraft carrier’s fighters scrambled off the deck – plenty of time to attack incoming planes that hand to come in at low altitude to drop torpedos.

But after 1930, technology started taking off. Airplanes became faster; the 100 mph torpedo bomber of 1930 was replaced by planes that could do very nearly 200 mph by 1935. The United States Marines invented Dive Bombing (with the Germans and Japanese enthusiastically copying the tactic)- meaning the enemy could not only come in at 200 knots, but do it at 15,000 feet, meaning interceptors needed to add that much more time to climbing to meet the enemy.

And the speed of ships started climbing, too; most of the world’s battleships in 1930 were red-lined at 23 knots (27mph); by 1935, the British, Germans and Americans had battleships on the drawing boards that could do 28-30.

And so when the Royal Navy decided in the early thirties that they needed a generation of aircraft carriers to fight the next war, it built them on the assumption that the technology of the attack would stay well ahead of the technology of detection – and that their carriers would have to thus be able to shake off plenty of damage and keep operating. The Illustrious class carriers first laid down i 1934 were fast enough to get away from enemy battleships, but armored well enough to withstand damage from lesser enemy ships, cruisers and destroyers. Most importantly, their flight decks were armored, to allow them to shake off bomb hits as well as protect the aircraft on the hangar deck down below.

Britain also scrupulously adhered to the arms control treaties of the day, in those innocent-seeming days when “arms races” involved warships rather than nuclear weapons; in addition to being bombproof, they had to come in under 24,000 tons. To do all that, something had to give; that something was capacity. Illustrious could hold 36 aircraft in its original form. The Admiralty figured it’d be better to have 36 aircraft that would get into action reliably than 52 on one of its older carriers that would risk getting sunk before launching an attack.

And given their initial assumptions and constraints (the “human eyeball” range of detection and the London Naval Treaty), they were correct.

But with war coming on fast, most of the world’s nations – especially Germany and Japan – stopped observing the London Treaty; ship displacement and firepower started creeping upward. And in 1936, the first radar set was tested, removing the “human eyeball” limit to detecting incoming attacks. And this revolutionized naval warfare just as much as it did war over land. When the United States Navy started designing it’s fleet of carriers, it did so knowing that it could “see” attacks far beyond visual range, day or night, allowing the carriers to scramble fighters to break up the incoming raid. and avoid enemy surface ships altogether. Carriers’ main defense became their air wings rather than their armor plating; with less need to ward off bombs and shells, the carriers could…carry. The American carriers that were being designed at about the same time – the Yorktown and Essex class ships that carried the US Navy through World War II and much of the Cold War as well – could carry between 72 and 100 planes. This made the huge carrier-borne sweeps later in the war possible. The Brits, especially early in the war, were limited to smaller, pinpoint raids against vital enemy targets. Their carriers just didn’t carry enough planes to carry off bigger operations.

Fortunately for the Royal Navy, just such an operation presented itself, seventy years ago tonight.

———-

The invasion of Greece showed Churchill that the Mediterranean was going to be anything but a backwater front in the war. This was no small issue for Britain; the key to the British Empire in the Eastern Hemisphere was the Suez Canal, which made communication with the vast bulk of the empire – India, Singapore, Australia, East Africa and many other holdings – cheaper and more feasible.

And since the Italians had a large army in Libya, it was vital to keep supplies going to Egypt to defend the canal. And to avoid a months-long plod around the Cape of Good Hope up to the Red Sea and thence to Suez, it was vital to keep supplies going across the Mediterranean.

And the Italian Navy had the potential to put a serious crimp in that supply line.

———-

Know what an awesome bit of technology a Ferrari Testa Rossa is? Italian ships were about the same.

Fast, well-armed, but with “short legs” – a very short cruising range – Italian ships were built for dashing across the restricted waters of the Mediterranean to hit enemy fleets and scamper back to base. And a huge squadron of them – six battleships, nine cruisers and a slew of destroyers – were stationed at the nail on the toe on the foot of the boot of Italy, at the base at Taranto.

It was nothing new. The British had been eyeing up the Italian Fleet as long as there’d been an Italy, for nearly eighty years. “How to remove Taranto” had played in several international crises over the previous century. There’d been many plans, many ideas; in the 1800s, the Admiralty had planned to take the city and port with the Royal Marines, in a pinch.

Well before the war began, the Fleet Air Arm was training in the exacting art of making torpedo attacks at night in shallow water. In November of 1940, they were the only fleet in the world that could carry the mission off. While most of the world believed it was impossible to launch airborne torpedos in a harbor (on the theory that the “fish” would plunge into the bottom before stabilizing themselves), the Brits figured it out before the Germans

And seventy years ago tonight, a British task force centered around the HMS Illustrious arrived 150 miles off the Italian coast…

…and launched 24 “Swordfish” torpedo bombers.

That’s right. Biplanes. Not a whole lot different than the ones that flew from Argus in World War I. During its Depression-era financing drought, the Royal Navy had enough money to build an excellent class of aircraft carriers – but had only just started figuring out the best airplanes to put on them when the war began.

But it was the software – the pilots and aircrew – that made up for the ancient equipment. They’d been training to do night-time torpedo attacks for years. In the days since Desert Storm, we take these sorts of things for granted; in 1940, night torpedo attacks from the air were just this side of science fiction, and almost entirely a function of navigation and piloting skill.

And at just before midnight, that’s what they did. Two of the 24 planes dropped bombs on the port’s oil tanks as a diversion, and then dropped flares over the harbor. Ten more dropped bombs on the cruisers and destroyers, mainly to keep the anti-aircraft guns busy. And the other 12 swept across the harbor, torpedoing three Italian battleships. Two – Littorio and Caio Duilio – were damaged severely enough to leave them under repair in the dockyard for months; the other, Conte Di Cavour, was out for the rest of the war.

The cost to be Brits? Two Swordfish shot down by Italian flak. One crew – two men – killed, one taken prisoner.

The attack changed the war in the Mediterranean; the Italians pulled their surviving ships out of Taranto and moved them farther up the coast to Naples, where their short range made their mission more difficult, and the longer approach made them more vulnerable to British submarines. They were never really a factor in the war again.

And it changed the rest of the war in even bigger ways. Because the commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Isoruko Yamamoto, had studied in the United States in the mid-twenties. He was familiar with naval history, including the desirability of sinking your enemy before he could sail to threaten you. He had read at the very least the reviews of The Great Pacific War, if not the book itself – and in any case, as a Japanese strategist in training, had been noodling about the idea of how to destroy the American fleet at Pearl Harbor (and the British one at Singapore, and the Dutch one at Surabaja) his whole career.

And the daring torpedo attack seventy years ago tonight at Taranto gave him and his staff an idea…

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.