It was seventy years ago today that Germany executed Fall Gelb– “Case Yellow” – the codename for the invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourge. About three weeks later, the operation continued with Fall Rot – “Case Red”, the invasion of France. We’ll come back to that one in a bit. Both nations – low-lying, largely few natural defenses other than the Rhein and Maas rivers, and saddled with the same sort of preventive neutrality that Norway tried to practice, fell quickly.

Rotterdam bombed by the Germans

The Germans’ goals weren’t just taking the three small countries – although Germany craved ports on the North Sea and, eventually, the Atlantic. The primary goal was to sucker the French Army to send their best troops charging into Belgium (along with their British allies) to the rescue – and to get cut off in Belgium and Northern France, while the Germans outflanked the Maginot line and charged into the heart of France.

The entire campaign was, in other words, a hip fake.

German Pzkw II tank in Holland in 1940. Outclassed by many French and British tanks, it nonetheless was often found where thos tanks weren't.

But it was a very risky hip fake. The Germans were trying to capture both countries with a minimum of force, to conserve troops for the real battle, taking out France and destroying or capturing the British Army on the continent. Many of the German troops were older reservists, from units that had been only half-trained. The Germans’ best troops – their most experienced Panzer divisions, their first-line infantry – were being saved for the push into France.

The Germans employed the first of what we’d today call “commando raids” to take a key obstacle, the Belgian fort at Eben Emael, manned by over a thousand Belgian troops with artillery and machine guns, which covered the key crossings of the Albert Canal and the Meuse/Maas river.

Armored observation cupola at Eben Emael, with a view of the terrain the Germans would have to cross. From this cupola, an observer would call down artillery fire on attackers.

A force of 78 German paratroops landed in gliders on the fairly undefended roof of the fort, and planted armor-piercing explosives on the gun turrets, silencing the fort’s main defense until the rest of the German army could cross the bridges below.

The German paratroopers that captured Eben Emael

Paratroops were the solution to a more difficult problem in the Netherlands. The Dutch had, since the 1600s, planned to defend the economic and industrial heartland of their flat, almost indefensible country by flooding the low-lying farmland east of Utrecht. The “Waterlinie“, or Water Line, created a putative “Fortress Holland”, effectively turning the nation’s heartland into a peninsula, nearly an island,with its east covered by the Water Line and a chain of forts, and the south by the Rhein River.

A Dutch fort/gun position astride one of the dijks at the edge of the Water Line. The dijk would be the only safe, dry road through the waterlogged, trench-ridden landscape. Dutch soldiers, so the plan went, would make sure invaders got an even drier welcome.

The Dutch flooded the water line well before the German invasion. But German paratroops captured the bridges over the Rhein, and poured troops across under complete air superiority, outflanking the Water Line for the first time since the 1600s, dooming the nation’s resistance.

The Netherlands fell, effectively, in a matter of days. Belgium held on longer – but it was, in fact, irrelevant in the greater scheme of things.

But as we’ve observed in the previous parts of this series, on the invasions of Poland, Norway and Denmark – American education has been sorely lacking at this part of history, unless the goal is to teach people media myths, not merely American but in fact German.

Over the decades, plenty of wives’ tales have come to be accepted as common currency.

“The Low Countries were weak and pathetic“. Well, yes and no.

Belgium and the Netherlands both realized, as did Norway and Denmark before them, that they had no chance fighting against any of the major powers, Britain or France or especially Germany. And like Norway and Denmark before them, they had spent most of the years since World War I embracing strict neutrality; not taking either side in any war. Of course, watching the world order fraying after about 1936 had caused alarm in both nations (and watching the Japanese grow ever more militaristic also spurred the Dutch, who at the time owned Indonesia as a colony) into belated action. Both nations started rebuilding their long-neglected defenses; both were too late, of course, but it wasn’t without effect.

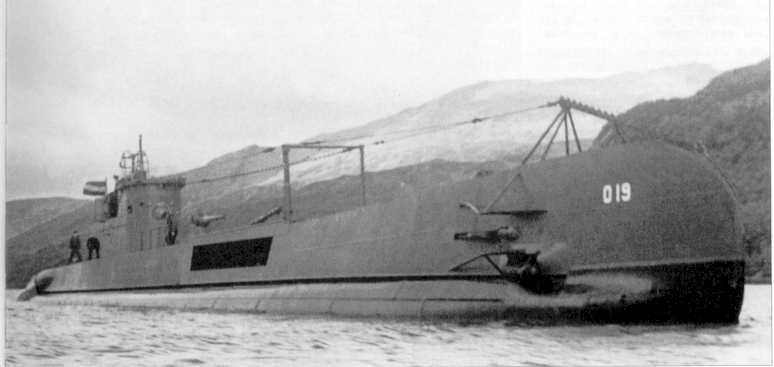

The Dutch submarine O19. When it was built, it was perhaps the best submarine in the world. It served with distinction through the war, being lost when it ran on an uncharted reef in 1945; its crew was rescued by an Ameircan submarine.

Along with the successful raids on Eben Email and the bridges to bypass the Water Line, the Germans tried again to cut the head off the Dutch Government and capture Queen Wilhelmina, landing paratroops at three airfields around the Dutch summer capitol at Den Haag. The paratroops suffered terrible casualties at each of the airfields; worse, the paratroops were unable to secure the area around the airports, so Dutch anti-aircraft fire destroyed many planed bringing reinforcements.

German Junkers 52 transport, destroyed on the ground at a Den Haag airfield by Dutch infantry.

Finally, Dutch counterattacks led each of the raids to retreat, with heavy casualties; over a thousand paratroopers were captured, and between Dutch antiaircraft fire and planes being caught on the ground by the Dutch infantry, the Luftwaffe lost half of its entire air transport fleet – losses that it keenly felt later in the war. The German paratroopers themselves were bled white by the resistance, and between the terrible losses in Holland and even worse losses the following year on Crete, the disaster led to the German airborne arm being grounded the rest of the war. Queen Wilhelmina, like Norwegian King Haakon before her, fled to the UK to lead a government in exile, lending the Dutch puppet government no legitimacy.

As the German panzers approached Rotterdam, the German paratroops that had taken the bridges tried to force their way across; a company of Dutch Marines in their striking black uniforms stood in the way. For the better part of four days. the Marines kept the two German forces apart, denying them one of their key routes into Fortress Holland. This resistance was a key part of the Germans’ decision, on May 14, to terror-bomb Rotterdam – the first of many terror-bombings in the West – and the threat of many more such attacks. The threat – and the carnage in Rotterdam, with 800 civilians dead – led to the Dutch government’s surrender.

And it was only then that the Marines gave up. The German commander was shocked; he expected a battalion of 800 Marijniers; as he saw the survivors of the company – 100 men and change – emerge from the rubble, he ordered his own troops to salute them.

According to Walter Lord in Miracle at Dunkirk, the Germans ranked their opponents in descending order of ferocity, tenacity and courage at the end of the 1940 campaign, according to the observations of German units in the field.

In order, they were the Dutch, Belgians, British, and finally the French.

The French Were Cowards: We’ll talk more about this in a few weeks, when we get to the actual invasion of France. But suffice to say it’s a lot more complicated than that.

While the histories of the era relate the supremacy of the German “Panzers” – tanks – in fact the French had more, and largely better, tanks than the Germans. It’s a truism among military geeks that the French employed their tanks badly, spreading them all over the front while the Germans concentrated theirs in a tight mass of steel that was sent slicing through the lines into the enemy’s rear.

But the French met the Germans in the biggest tank battle in history (until the huge battles in North Africa and Russia later in the war), the Battle of Hannut, in which French tank and infantry, fighting with the kind of skill that the legends of French cowardice have found too inconvenient to remember, held the Germans to a tactical draw and an operational defeat. halting a German armored advance.

French tanks, destroyed in action at Hannut.

The French victory turned out to be more or less irrelevant – the real attack came a few days later, through the Ardennes Forest, the same place where Germans had attacked to rout the French and Belgians in 1871 and 1914, and where they’d surprise the Americans in the winter of 1944. This attack caught the French, Belgians and British by surprise, crossing the Meuse river (in one of the cases where French troops – thirty-something reservists, mostly – actually did break and run under heavy attack from German Stukas. The attack drove straight to the English channel in a matter of four days, cutting off the troops that had prevailed at Hannut and many other places along the northern front.

And it was there, really, that the Battle of France was decided. France’s best troops – their elite, their best-equipped, their tanks, their best of everything – had raced north to rescue the Belgians. Although three weeks and change would pass before the actual invasion of France, the initial plan – to draw the French and British into Belgium and cut them off – succeeded brilliantly. The entire British Expeditionary Force, and a third of the entire French Army, was trapped in Belgium and northern France. They would engage in an epic retreat to Dunkirk, and be snatched from the jaws of disaster by an epic national response…

…but we’ll get to that in a few weeks.

Strange, but in the 19th century the French victories were largely due to superior leadership and staff work. In the 20th century, the lack of French victories was largely due to the fact that what floated to the top of the French military was the stuff that floats to the top in a cesspool. The problem was largely political, unfortunately.

One example that sticks out (and no doubt you’ll expand on) was how tanks were used. The French treated them as little more than close support mobile artillery to support infantry rather than an integrated attack force like the Germans did.

The French treated them as little more than close support mobile artillery to support infantry rather than an integrated attack force like the Germans did.

To be fair, in 1940 the Brits and Americans were about the same.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Shot in the Dark » Blog Archive » Fall Gelb -- Topsy.com

Nerdbert, I’m still trying to get grip on 19th-20th century French history. Petain, hero of the 1st World War, a dirty word after the Second World War. The French have always seemed to leap the wrong way, towards belligerence when peace would have served them better, towards pacifism and complacency when it empowered their enemies, towards fascism when the war against fascism was all but won, towards Marxist-Leninism when even the Soviets didn’t believe in in it anymore . . .

I enjoy your historical writings, Mitch. Keep it up.

To be fair, in 1940 the Brits and Americans were about the same.

True enough, although the Americans had some insurgents who were fighting the system fairly effectively and by 1940 the organization of the armored units had begun to change. After all, Christie’s impact on tactics, armor, and design however slowly learned by the American Army can’t be understated. It’s not without irony that the Russians learned the lessons of Christie and his tank the best, but that was probably because they weren’t unlearning the lessons of WWI.

your WW II writings are some of my favorites.

Pingback: Shot in the Dark » Blog Archive » As You Remember

Pingback: The Greenroom » As You Remember Our American Heroes

Pingback: I Heard It On The NARN | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: Blast From The Past | Shot in the Dark