The guns that roared to life across the Bulgarian/Greek lines in Northern Macedonia on September 14th, 1918 had been expected for some time. What had been a relatively quiet front for the better part of three years since the Allied landings at Salonika had come to life since late May of 1918 as the “Allied Army of the Orient”, a cosmopolitan assortment of divisions cobbled together from Britain, France, Italy, Serbia and finally Greece, slowly began to advance. Opposing them had once been an equally mixed grand alliance of Central Powers divisions, which had slowly melted away into just two depleted Bulgarian armies.

800 Allied artillery pieces struck the Bulgarian trenches at Dobro Pole (“Good Field”) and Allied aircraft bombed the supply chain behind the line. The barrage would continue into the next day, doing little direct damage to the Bulgarian line but carving up the barbed wire defenses and clearing paths through no man’s land. In many ways, the Allied offensive looked the same as literally dozens of others over the past four years on battlefields across Europe and the Middle East. But as Allied soldiers finally hit the Bulgarian trenches, suffering tough casualties, the outcome was profoundly different. The Bulgarians broke. Like the Germans in Amiens just a month earlier, the average Bulgarian soldier no longer wanted anything to do with the Great War.

What had been hoped to be a minor Allied offensive to regain ground lost to the Bulgarians earlier in the war turned into a rout. And the first of the Central Powers would fall.

Bulgarian trenches – Bulgaria had managed to hold off a massive Allied army largely by themselves for nearly years

In many ways, the Salonika Front had been frozen in place since late 1916 as first the Central Powers, and then the Allies, had tried in vain to quickly end what had become yet another tertiary front sapping men and materials badly needed elsewhere. The Germans had coordinated with Greek King Constantine to allow German and Bulgarian troops to invade Northern Macedonia in an attempt to expel the Allied encampment at Salonika. The move prompted the overthrow of the Greek monarchy and an Allied counteroffensive that regained some of the lost Macedonian territory but otherwise locked the two sides into the same positions they’d share until the summer of 1918. Forces for both sides would come and go as needs on other fronts dictated, with the Russians leaving Greece with the fall of the Tsar and the Turks leaving as their Arabian and Mesopotamian Empires collapsed. But the battles were few and far between, with the Allies referring to the front as “Muckydonia” due to it’s mud and boredom and the Germans mockingly calling Salonika “their largest POW camp.”

As more and more German troops were required elsewhere, the burden of holding the Salonika Front increasingly fell on Bulgaria. The Bulgarians had been at war almost non-stop since 1912, first as one of the victors of the First Balkan War against the Ottomans and then as the loser of the Second Balkan War as the Bulgarians invaded their former allies in Serbia and Greece in a bid to undo what they felt were inadequate territorial gains. The nation had barely recovered from the loss when approached to join the Central Powers with the offer of parts of Macedonia. Tsar Ferdinand leapt at the chance to undo his defeat and promptly announced the mobilization of the army for the third time in four years. It was an exceptionally unpopular move.

Other than Prime Minister Vasil Radoslavov, who had pushed for the country to embrace the Austro-Hungarians and abandon the Russians after the perceived lack of support of Bulgaria’s Balkan War claims from St. Petersburg, there was little support for yet another war. A coalition of political leaders met with the Tsar just days before Bulgaria joined the war, imploring him to wait and help build popular support. The head of the powerful opposition party, the Agrarian Union, Aleksandŭr Stamboliyski, warned Ferdinand that a rush to join the Central Powers would lead to another Second Balkan War disaster. “Don’t worry about my head, I am old,” Tsar Ferdinand told Stamboliyski. “Think about your own, which is still young.” If the threat wasn’t obvious enough, Stamboliyski found himself arrested and sentenced to imprisonment for life upon leaving the meeting. Politics weren’t going to ruin Bulgaria’s chance at empire.

Bulgarian officers salute one another

As the years progressed on the Salonika Front, the Allied position continued to consolidate while the Central Powers slowly, but surely, weakened. The Greeks had formally joined the war effort in 1917, bringing an additional 24 divisions to the fight. Meanwhile, pressed by the Romanian Front and needs in France, Germany’s commitment to Salonika dissipated. Yet the 18,000 German troops at the front consumed resources on a massive scale. The Bulgarians complained they were parting with ammunition, fuel and food the equivalent of 100,000 men for the 18,000 Germans. And like most of the warring nations, Bulgaria was starving. Grain production was cut in half as nearly 40% of the entire male population of the country found themselves drafted. Bread was now being made with corn husks. One non-commissioned officer bluntly told the Bulgarian Chief of Staff: “We are naked, barefoot and hungry. We will wait a little longer for clothes and shoes, but we are seeking a quick end to the war. We are not able to hold out much longer.”

With an increasingly unified Greece, the Allies went on the offensive in May of 1918, scoring a minor tactical victory at Skra. The scale of the victory was less than impressive, with only about 3,000 Bulgarian casualties and a very small amount of Greek territory reclaimed. But the Bulgarian line had finally managed to be pierced and most of the Bulgarian losses were prisoners. Just like what the Germans would experience a few months later, the Bulgarians were forced to halt counterattacks to retake Skra because their officers were unable to motivate or threaten their men to march to the front. The Bulgarians were in serious danger of losing control of their army. And unlike the Germans a few months later, Bulgaria was willing to accept that outcome and would try and negotiate their way out of the war.

Vasil Radoslavov was ousted as Prime Minister and the Bulgarians began trying to see if they could get favorable terms for their Macedonian claims from the Allies. At the same time, the Bulgarian General Staff implored Hindenburg to send reinforcements. Neither move yielded success. The British weren’t going to throw the Greeks under the bus by supporting Bulgarian claims and Hindenburg did precisely the opposite of what the Bulgarians asked – he removed more troops to prop up the now failing Spring Offensive. Tsar Ferdinand wasn’t dissuaded; the Bulgarian Army still occupied portions of Greece and had yet to suffer a major defeat.

Bulgarian field artillery opens fire

That was about to change on September 14th, 1918 as the Allied Army of the Orient pressed into the Bulgarian line. The Allies hoped to push the Bulgarians over the Vardar river, giving the attack the commonly used name of the Vardar Offensive. At first, the Bulgarians generally held, suffering casualty rates in the 40-50% range and causing similar brutal losses for the Allies. But within 48 hours, the gap in the line was 16 miles wide and 4 miles deep and Allied airplanes were bombing the last bridges over the Vardar. Bulgarian efforts to counterattack dissolved as reinforcements jammed on roads filled with retreating soldiers and reserves refused orders to attack. By September 18th, the Bulgarian line around Vardar had broken and subsequent Allied assaults opened up other sectors of the front, albeit sometimes at a tremendous cost in lives. Some Bulgarian units fled with barely a shot; others fought to the last man.

There was soon to be a third category of Bulgarian troops – those who were actively rebelling and attempting to start a revolution.

As some Bulgarian units retreated, they began looting cities and villages along the way. Others turned on their officers. In hopes of preventing a Russian-like revolution, Tsar Ferdinand invited the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union into power and released Stamboliyski from his life sentence. Stamboliyski was willing to work with the government to try and negotiate a quick end to the war; the rest of the Agrarian Union was not. In the town of Radomir, the group declared a Republic and started recruiting fleeing soldiers into their ranks. While the military numbers of the “Radomir Revolution” numbered but a few thousand, the revolution marched on Sofia with little opposition and captured the capitol.

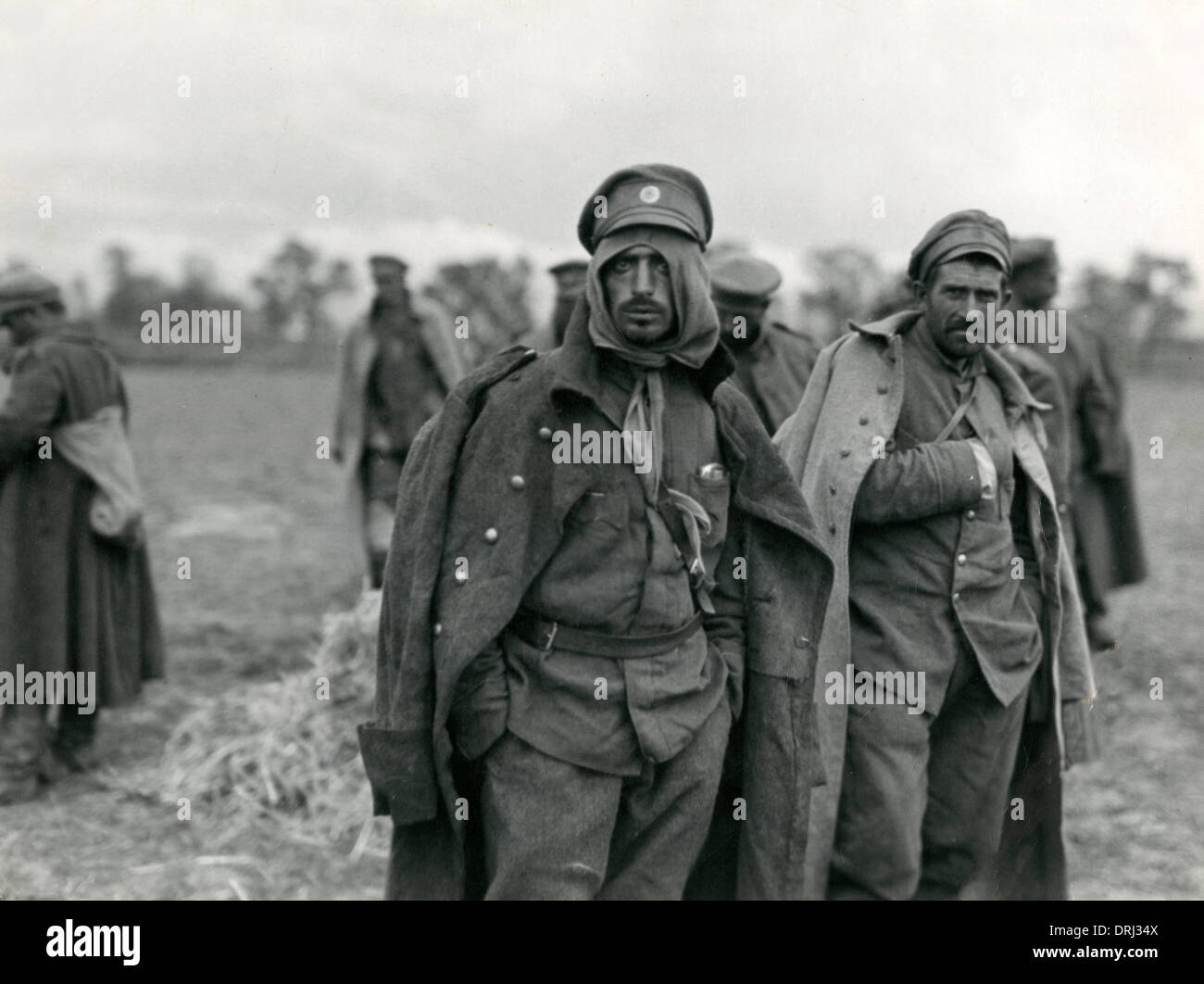

Bulgarian POWs – these men actually have a fair amount of clothes on them; many Bulgarian troops by this point could barely clothe themselves

The Bulgarians panicked and immediately asked the Allies for an armistice. In a preview of coming attractions, the Bulgarians believed they could leverage the U.S. Consul General to help negotiate generous terms since Bulgaria hadn’t declared war on the United States. The Allies weren’t interested and demanded what amounted to an unconditional surrender. The only concession the Allies granted was that Bulgaria wouldn’t be occupied by Serbian or Greek troops and only British and French troops would be given free passage through the country to attack Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. With rebels marching on Sofia, and their Central Powers allies stating they could only muster six divisions to reinforce the front, Bulgaria sued for peace.

The repercussions could be felt across the entire war. Not only had the Balkan Front collapsed, but now Austria-Hungary’s southern flank and the Ottoman’s western flank next to Constantinople were exposed. Neither dying empire had the resources to check any significant Allied advance, throwing the fate of both Central Powers nations into disarray. Defeat also meant the surrender of the German 11th Army, netting the offensive a total of 50,000 prisoners. While Bulgaria signed the armistice, in Germany Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff requested an audience with the Kaiser. They told him they couldn’t guarantee the security of the Western Front for “more than two hours” and that the Bulgarian defeat meant that the war was lost. Both generals offered their resignations; Wilhelm accepted Ludendorff’s resignation but refused Hindenburg’s. For Ludendorff, this was the last straw and he refused to have anything more to do with Hindenburg. In the following months, Ludendorff went underground, attempting to escape Germany as he was sure he would be arrested or executed by the various groups that came to blame him for the defeat.

As Tsar Ferdinand fled Bulgaria for Germany, leaving his son Boris III in charge to successfully crush the revolt, Kaiser Wilhelm II summarized the effect of the defeat in his telegram to the ousted Tsar: “Disgraceful! 62,000 Serbs decided the war!”

suffering casualty rates in the 40-50% range – with such an enormous attrition rate, how the heck did the war last as long as it did!

“Disgraceful! 62,000 Serbs decided the war!” – Never the elite’s fault. Turn to 2021, lather, rinse, repeat.

Great series First Ringer.

As I understand it all armies with the exception of the US suffered various levels of mutiny and desertion. Did American forces ever refuse to fight?

There were about 5,500 cases of Americans who deserted during the Great War, but until the rest the warring armies, none of them were executed. But that’s as much a function of timing as anything as the war ended and Wilson commuted the sentences of those who would be shot.

Pingback: In The Mailbox: 07.09.21 : The Other McCain

Pingback: Judgement Day | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: On the Line | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: Pèace de Résistance | Shot in the Dark