We’ve fallen a little behind on our World War I series. Over the next few weeks/months, we’re going to work to get caught-up to the calendar.

The call to early morning prayers (the fajr) had reverberated throughout Mecca on June 10th, 1916. The modestly-sized city of less than 80,000 was only just beginning their day as Hussein bin Ali, the Ottoman-appointed Sharif of Mecca, strode to the balcony of the Hashemite Palace.

Despite the conflicts to their East in the Sinai and Mesopotamia to their West, the holiest city in all of Islam, home to the Masjid al-Haram or “Sacred Mosque,” had been remarkably quiet. Most of the Ottoman troops stationed in Mecca had been relocated, leaving only a skeleton force of a thousand men. A large military presence in the holy city, the site of the Prophet Muhammad’s triumphant return following years of exile in nearby Medina, was otherwise considered unseemly.

From the balcony of the Hashemite Palace, a shot was fired into the air. As the echo coasted down the city streets, 5,000 men began firing upon the Ottoman fortresses that dotted the town. Peering out from behind one of the fortress walls, the Ottoman commander quickly telephoned Sharif Hussein bin Ali – who was attacking them? Both the attackers and defenders were flying the same flag of the Kingdom of Hejaz, the regional authority of the Ottoman Empire. Were these attackers Bedouin? Ottoman deserters? The British? No, Sharif Hussein bin Ali replied – they were his troops.

What would become known as the “Arab Revolt” had begun. And the era of Ottoman control of the desert was about to end.

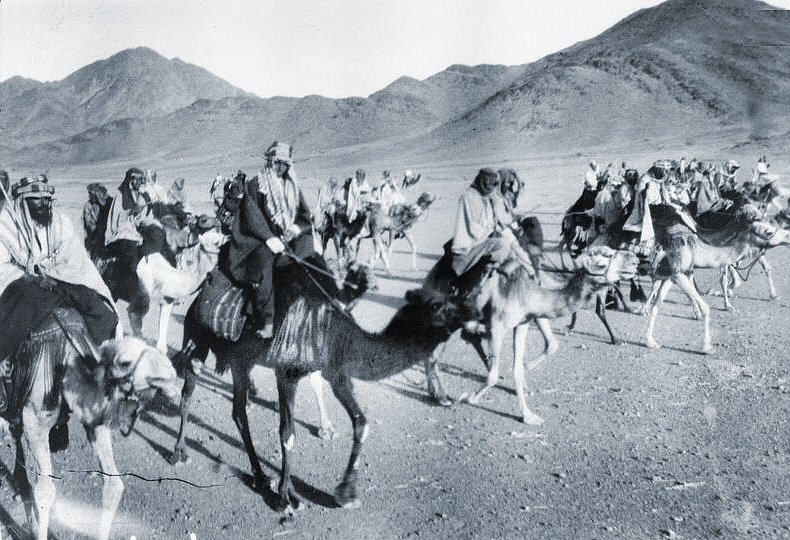

Arab Revolt – the romanticized view. In reality, it would become a brutal conflict and one heavily subsidized by the British

In the summer of 1916, the dichotomy of the politics of the Arabian Peninsula were profound. Nowhere else in the Ottoman Empire was a region governed by men so willing to rebel, yet leading over a populace so apparently disinterested in doing so.

The rise of nationalism in the late 19th/early 20th century had long since started the process of political division within the Empire. Albanians, Greeks, Serbs, Kurds, Armenians, Jews and Turks had all begun to compete for power within the fractured status of Ottoman rule. In some cases, the result was independence from the Empire, as in the cases of Greece and Serbia. In other cases, the strive for political autonomy was either granted (Albania), but mostly it was brutally repressed (Armenia). Yet while the Ottoman Empire was being torn apart by ethnic divisions, the largest minority population of the Empire barely expressed any interest in political power.

For the Arab populations of the Ottoman Empire, their cultural or ethnic identity was housed within their tribal allegiances. The very concept of being “Arab” was for those defined as such, at best, a misnomer. They were Bedouins. Or Hashemites. Or perhaps defined by their religious adherances as Sunnis or Shittes, if they were Muslim at all – 19% of the Empire was Christian in 1914, with large Christian Arab populations in places like Lebanon. And the few Arabs who expressed interest in gaining additional political power were wildly different in their goals. While the first “Arab Congress” in 1913 demonstrated that at least some Arabs held westernized political ideals, the group was only representative of cosmopolitan Syrians and Egyptians. The tribal leaders of the desert weren’t present at such meetings, nor were their political interests even considered. Coupled with the fact that the conference took place in France, and not within the Ottoman Empire, there were few “Arabs” in the Arab Congress.

The Ottoman Parliament in 1915 – despite being the largest minority group in the Empire, there was no real political unity among those who might call themselves “Arabs”

Such political disinterest ended with the “Young Turk” revolution of 1908. The return of constitutional authority and the Ottoman parliament suddenly thrust the Empire’s Arabs into political prominence. Of the new parliament, 60 Arabs were elected – the second largest contingent in the Empire, after the 142 elected Turks.

These newly-empowered Arab leaders quickly discovered they didn’t have an ally in Constantinople. For decades, the regional authority of Arab Muslim leaders had been slowly stripped away. Between the increasing centralization of the Empire, and growing Christian and Jewish populations, Arab Muslims had less power than they had wielded in centuries. The process only accelerated under the leadership of the Young Turks. The Ottoman Empire would simultaneously be more Westernized and democratic, and yet more centralized under the ruling thumb of the Empire’s ethnic Turks. In response, the Arab representatives supported a counter-coup in 1909 to try and restore Abdul Hamid II back on the throne. Hamid II might have been a despot – he had overthrown constitutional rule in 1878 – but he was a Muslim despot, and one who could only rule through powerful regional subordinates.

Among such subordinates were men like Sharif Hussein bin Ali. Appointed by Hamid II as Sharif of Mecca right as his rule ended, Hussein bore little in common with the Arab political intellectuals of Beirut or Damascus. A direct descendant of Muhammad through his grandson Hasan ibn Ali, and one of the leaders of the Hashemite tribe, Hussein was not exactly the epitome of an Arab chieftain. Fairly well educated, Hussein was home schooled as opposed to learning his leadership skills out in the desert with the Bedouin, as was customary with those on track to become a sharif. But he was also very religiously conservative, unlike the secular Arab revolutionaries of the coastal cites of the Middle East.

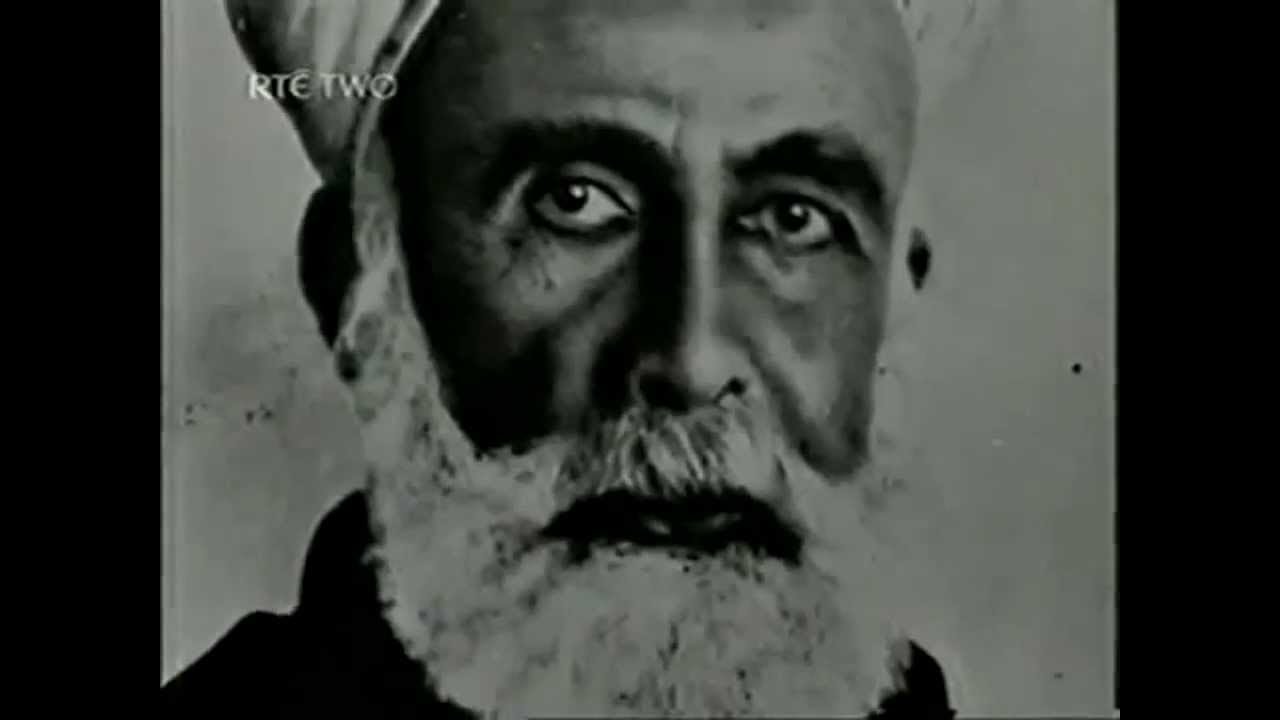

Sharif Hussein bin Ali – the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein was fearful of being deposed by the Turks once the Great War ended

Sharif Hussein’s stature – both in terms of his political power and religious lineage – caught the attention of the British Arab Bureau. Hussein was no “pan-Arabist,” much to the chagrin of some in London who were searching for a Arab nationalist champion. The Sharif of Mecca did harbor grand illusions of power, perhaps as the King of Hejaz or even the “King of the Arabs,” but Hussein’s interest in such schemes began and ended within the fortunes of his Hashemite tribe.

Hussein had managed to avoid entangling himself within the Ottoman war effort, but the pressure from Constantinople was increasing. Hussein’s passivity in recruiting Arabs to join the army had led to rumors that the Ottomans favored Hussein’s rival, Sharif Ali Haider, for the control of Mecca after the war was over. Urged by two of his sons, Abdullah and Faisal, Hussein warmed to the idea of British support.

With the British promising Hussein an Arab empire covering the entire span between Egypt and Persia, with the exception of British possessions and interests in Kuwait, Aden, and the Syrian coast, and Hussein boastfully claiming he could get 100,000 Ottoman soldiers to defect, an alliance of convenience was born.

Faisal – he was far more cunning and ruthless in his political dealings than the image created by the movie “Lawrence of Arabia”

The flaws in the British-Sharif Hussein partnership became painfully clear from the beginning.

First and foremost, Hussein lacked the power and influence the British had projected upon him. While Hussein had rallied 5,000 men to his cause in laying siege to Mecca, the under-manned and under-supplied Turks of the city’s garrison could not be forced to surrender. Only after the British had provided trained Egyptian artillery had Hussein’s “Arab Revolt” managed to occupy the town.

Despite massive assistance from British propaganda, Hussein had as much trouble recruiting Arabs as he did winning battles. Few Arabs, outside of Bedouin stragglers, were willing joined Hussein’s revolt. At best, Hussein’s “Sharifian Army” likely had only 5,000 regular soldiers. Stationed at the British-controlled port of Jeddah, it was becoming apparent that Britain had cast their lot with a weak, isolated ruler who didn’t even share London’s ideals of an semi-independent, British-aligned, Arabia.

The Hashemite Army – the Arab Revolt would be split into three groups. The Arab Northern Army, or the Hashemite Army, would be the guerrilla group history would remember

If Sharif Hussein bin Ali didn’t fit the pan-Arabist mold Britain had hoped to discover in the desert, his sons did. Abdullah bin-Hussein, Ali bin-Hussein, and Faisal bin-Hussein were far closer to being Arab nationalists than their father would ever be. All three had been raised or educated in Constantinople, and Abdullah and Faisal had both been members of the Ottoman parliament. Each played upon a different strength: Ali bin-Hussein, the oldest, was the heir to the Sharif of Mecca and even Caliph, providing him with significant religious influence. Abdullah, the second-oldest, was the diplomat – having sought out Lord Kitchener himself in 1914 to broach the idea of an alliance. And Faisal, the youngest, may have been the most ambitious of the three, showing a willingness to ally himself with forces as long as they provided him with an advantage – rival tribes, the British, and (later) even the Ottomans.

Such division of power among Hussein’s sons did not serve the Arab Revolt well in the beginning. While Ali bin-Hussein worked to consolidate his father’s influence in Mecca, Abdullah sought out closer ties to Britain, as Faisal launched his own, Bedouin-led offensive. Hussein’s limited resources were scattered across western Arabia, as each son seemingly attempted to direct their own war.

Despite their differences in desired approach, the outline of a revolution was starting to come into place. Hussein’s Sharifian Army of loyalists might have been painful small, but it was now growing with Faisal’s recruitment of fellow Hashemites and Bedouins into a mobile guerrilla force. Trained by former Ottoman colonel Aziz Ali al-Misri, Faisal’s mercenaries were poised to strike into the interior of Ottoman-held Arabia. The only major remaining question was who was in charge of his new army – Hussein, his sons, or their British allies?

Abdullah – he would find himself minimized during the Arab Revolt but would go on to become Abdullah I, the ruler of Jordan

By the fall of 1916, the trend had become clear – wherever the Arab Revolt marched, it won; as long as it had British military support.

Several port cities, and 6,000 Ottoman prisoners, had fallen to the Revolt. In each case, British naval dominance had been the decisive factor, hammering the fixed Ottoman positions until Hussein’s Arab forces could occupy them. When the Arabs had attempted to strike the Ottomans by themselves, they were routed. An offensive against Medina, led by Faisal, was easily repulsed by the Turks, with major Arab casualties.

These outcomes had led to a literal division of forces. Hussein’s loyalists, the Sharifian Army, became a conventional army in the Western style. Faisal’s mercenaries were the Hashemite Army, a guerrilla force that Faisal hoped could still acquire territory like a conventional army. Both forces were nominally under Hussein’s control, with a mixture of British, French and former Ottoman advisers. But as casualties and defections took their toll, the Sharifian Army was increasingly a non-Arab fighting force, with little loyalty to Sharif Hussein. Made up now largely of Ottoman POWs, the army was for all intents and purposes a British unit.

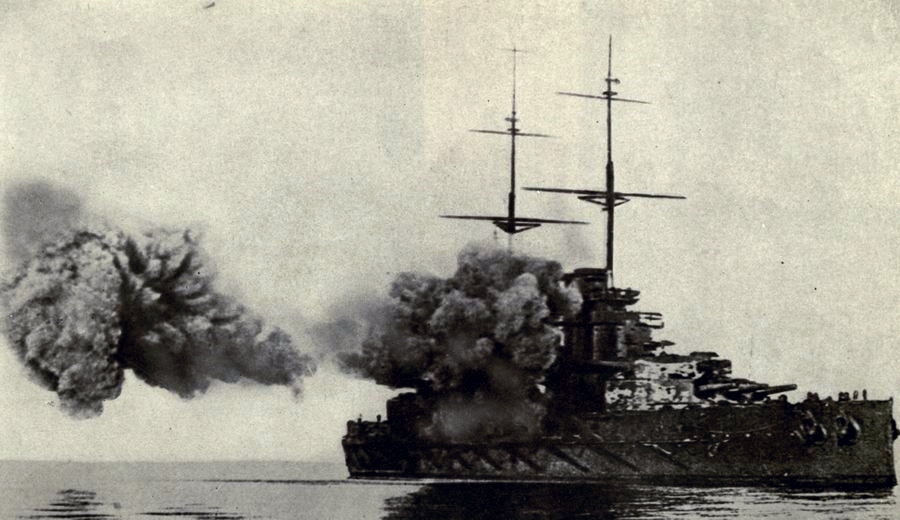

British bombardment – without British naval assistance, the Arab Revolt might have been over before it started

Both Abdullah and Faisal were eager for the Hashemite Army to avoid the same fate as the Sharifians. The brothers ignored the advice of their allied advisers. The Sharifian Army could endlessly drill in Jeddah all it wanted; the Hashemite Army would advance into the Hejaz and harass the estimated 15,000 Ottomans holding down southern Arabia. The Arab Revolt didn’t need British advisers or Ottoman castoffs – it would win with Arab soldiers.

Abdullah and Faisal’s desire for operational independence would be put to the test early in the revolt.

After enduring six months of guerrilla attacks along the Hejaz railway, the communication line linking southern Arabia with the rest of the Empire, the Ottomans finally decided to put an end to Sharif Hussein’s uprising. Marching three brigades out of Medina on December 1st, 1916, the Ottomans set their sights on the nearby port of Yanbu. If captured, the Arab Revolt would lose access to British reinforcements via the Red Sea and possibly be forced to retreat halfway back to Jeddah. Militarily, the Revolt could probably stand to lose Yanbu, but politically, the move towards consolidation under the Entente would be almost unstoppable.

The Ottomans easily swept the Hashemite Army aside and within days, had Yanbu surrounded. The Revolt was so desperate, they constructed an airfield in the city in hopes of getting British aircraft to fly in supplies – a novel concept in 1916. Instead, one of the Hashemite Army’s British advisers managed to convince his superiors to send in warships to weaken the Turk’s grip on the port. Pounded by British naval guns, and harassed by seaplanes launched from the HMS Raven II, the Ottoman offensive petered out within less than two weeks. By January 18th, 1917, as the Hashemite Army counterattacked, the Ottomans were forced to retreat back to Medina.

Supplied with armored vehicles, machine guns and massive amount of money to bribe the Bedouin tribes, the new Hashemite Army would create havoc in Arabia

The Hashemite Army had survived the Ottoman’s trial by fire – but only with British help. There was little question now that the Arab Revolt was incapable of progressing beyond holding a few cities in the Hejaz without British assistance. Neither Abdullah or Faisal had trusted Britain’s intentions in Arabia, but where Abdullah was resolute in refusing British aid, Faisal saw the opportunity for a military bargain.

Faisal approached the British adviser who had managed to secure the naval bombardment critical at Yanbu – a low level Arab Bureau operative who had just months earlier been a cartographer in Cario. Faisal would support the larger British war strategy for the Middle East, if he was given operational control over the Arab Northern Army. The young British adviser told his superiors that Faisal might be the sort of pan-Arabist figure they were looking to groom, and Faisal was soon the recipient of British aid to his ragtag Hashemite forces. If the Arabs were going to be forced to be junior partners in their own revolt, by Faisal’s mind, at least he was going to be the one leading them.

Faisal’s Army would play a minor role in the war to come, but his alliance with his young British adviser, T.E. Lawrence, would soon dominate the headlines.

T.E. Lawrence – the Arab Revolt was full of foreign advisers, but none matched the marketing skills of Lawrence

Pingback: In the Mailbox: Early Morning Weakened Edition : The Other McCain

MBerg: IMO, some of your best work is your historical writing.

The fighting in Arab and Muslim lands is so intense and vicious because it is an internal fight. It is a fight over the meaning of the Muslim faith. It is a fight over the acceptance or rejection of modernity vs. traditional morays and social organization. Western Society plays a role, because it has supplied the money, the weapons, and the modernity, but they are outsiders. The war is a civil war, a war of ideas fought between close relatives over the direction of their society. History says that modernity and a less aggressive form of Islam will win, but that outcome will likely take generations to come about.

Emery,

While I thank you – and I truly enjoy the historical stuff – this piece is the work of First Ringer, who covers the “obscure historical nooks and crannies” and “Southwest Metro Conservative Strategy” desks at SITD.

Pingback: The “Brilliant Victory” | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: Nothing Is Written | Shot in the Dark