On August 14th, 1945, the Second World War had but hours to go.

Since the atomic bombings and Soviet invasion of Manchuria just days earlier, Japan had begun secret communications through the neutral powers of Switzerland and Sweden to accept the Allies’ demands for unconditional surrender. Unbeknownst to all but a few within the government and military, Emperor Hirohito had already recorded a radio address to accept the Potsdam Declaration. The recording would be played on August 15th and subject Japan to an unknown fate in the hands of the Allied powers.

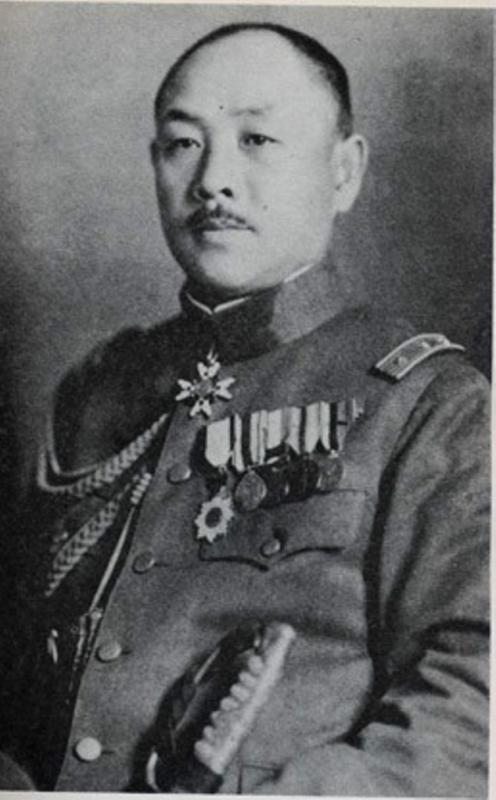

Major Kenji Hatanaka knew of the Emperor’s recording on the night of August 14th as he and a group of fellow officers entered the Imperial Palace. Hatanaka burst into the office of Lt. General Takeshi Mori, the commanding general of the 1st Imperial Guards Division whose troops were responsible for defending the Palace and royal family. Hatanaka made his intentions plainly known – he and his co-conspirators intended to stop the Emperor’s broadcast and continue the war. Mori was horrified; Hatanaka and his men were violating an explicit order from their superiors. Mori immediately demanded that Hatanaka return to his barracks.

But Kenji Hatanaka was not going to be following orders on this night – he was going to be giving them. Hatanaka and his officers quickly shot Mori and Mori’s visiting brother-in-law. Using Mori’s official stamp, Hatanaka forged Strategic Order No. 584 – an order to surround the Palace and prevent anyone from coming or going. The 1st Imperial Guards Division was now at Hatanaka’s disposal and the Emperor was, in essence, his prisoner.

The end of World War II rested upon Japan’s ability to withstand a coup.

—

Major Kenji Hatanaka – the mastermind of the August 14th coup. He was only 33 years old and managed to convince older, higher-ranking officials to take his orders

Just days earlier, Tokyo had seen two different conferences attempt to address the end of war – each with very different conclusions.

On the night of August 12th, well into the morning of August 13th, Japan’s Supreme Council for the Direction of War had continued to debate whether acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration meant the removal of the Emperor. The Declaration had been vague on specifics on the Emperor’s fate, noting that not only would war criminals be subject to punishment but that the “authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest” would be permanently eliminated. Coupled with the Allies’ military occupation of Nazi Germany as a model, many senior Japanese officials were hesitant to agree to anything that might result in the end of the Japanese Imperial system of government.

At midnight, the debate was no longer theoretical. The Allies broadcast from San Francisco a message to Japan – the Emperor’s authority would be subordinated to that of the Allied powers in the event of an occupation. The Japanese monarchy, in existence since 660 BC, would be rendered powerless if Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration.

Gen. Korechika Anami – the Minister for War and the “most powerful figure in Japan besides the Emperor himself.” Anami refused to support the coup but did nothing to discourage it either

The Supreme Council for the Direction of War had already wrestled with the weight of the decision. The debate was over – Japan would accept the Declaration and surrender.

The decision was far from unanimous. That same night, a small group of younger officers, including Hatanaka, held their own make-shift conference with the most influential member of the Supreme Council, War Minister Korechika Anami. Deemed the second most powerful man in Japan to the Emperor himself, Anami had been a passionate advocate for Japan’s war of expansion. Even in the wake of the atomic bombings (Anami proclaimed the Americans could only have one bomb, so Japan shouldn’t overracted to Hiroshima), Anami had dutifully recited the Japanese military line that the war could only end with a massive, decisive battle on Japanese soil. Hatanaka and his allies rightly assumed Anami would aid them in an effort to overthrow the government.

Instead, Anami demurred. With the Supreme Council’s decision fresh in his mind, Anami would neither support nor oppose Hatanaka’s course of action. It wasn’t the response Hatanaka expected, nor needed, but in his mind it had left the door open to a coup. Perhaps once Hatanaka and his supporters took action, Anami might join them to lead the effort.

Anami believed he had deflected the question; Hatanaka believed Anami had given him his silent consent. Both were tragically wrong.

—

Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki – taking over the post at the age of 77 following Okinawa, Suzuki would resign following the announcement of the surrender

On the night of August 14th, as Hatanaka and his small band of rebels tore apart the Palace frantically searching for the Emperor’s recording, another wing of the coup plot attempted to assassinate the man they believed responsible for forcing the Emperor to surrender – Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki.

The rebel officers hoped to catch Suzuki by surprise at his office. They discovered nothing more than paperwork and an empty chair behind his desk. In their frustration, they machine-gunned the office and then burned Suzuki’s home. The effort to behead the government had failed, but had nevertheless terrified the authorities. Suzuki would spend the following weeks before the formal surrender in hiding.

The effort to recruit the support of the Japanese Army was failing as well. Little did Hatanaka know that a number of other senior officers had foreseen such a coup attempt just the night before. In a tense meeting, the key military members of the Supreme Council and War Ministry had signed a pledge to honor their Emperor’s orders to surrender – including Anami. The support of the highest ranking members of the Army undercut any effort by Hatanaka or others to enlist support of a coup. And as Anami took his own life that night out of shame for losing the war, stating in his suicide note “I—with my death—humbly apologize to the Emperor for the great crime,” any hope that the military would change it’s position vanished.

—

Hirohito records his acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration: “We have resolved to pay the way for a grand peace for all generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is unsufferable.”

By 3am on the morning of August 15th, the last threads on Major Kenji Hatanaka’s coup were unraveling.

Informed that the Eastern District Army was marching on the Palace, Hatanaka desperately pleaded with the District’s Chief of Staff to allow him to go on the radio. Perhaps if he could broadcast his message to the people, they’d rise up against those in favor of surrender. Or at worst, perhaps Hatanaka could justify to the public at large his disobeying of orders and reduce the dishonor his actions had put upon his family. Not surprisingly, the Chief of Staff refused.

As the sun rose that morning, the coup attempt was over. The Eastern District Army retook the Palace without a fight, amazingly letting Hatanaka and his co-conspirators go free. A despondent Hatanaka jumped on a motorcycle, bizarrely driving around Tokyo throwing leaflets explaining his reasons. By 11am, Hatanaka had taken his own life with his pistol; a note on a his body stating “I have nothing to regret now that the dark clouds have disappeared from the reign of the Emperor.”

—

Gen. Takeshi Mori – despite killing the head of what was in essence the Palace Guards, the coup ringleaders were let free. Whether the authorities knew that Mori had been murdered when they did so was unknown

Hirohito’s broadcast occurred without incident. The recording had been hidden in a laundry basket and transported out of the Palace right past the rebelling soldiers.

The message, known in Japanese as the Gyokuon-hōsō or “jewel voice broadcast” was not only the first time the Japanese public had heard their Emperor’s voice, but was likely the first time any Japanese civilian had heard any previous Emperor speak. Spoken in a classic Japanese dialect, and strangely obtuse in it’s message, few who heard the broadcast could immediately understand the significance. “How are we to save the millions of our subjects, or to atone ourselves before the hallowed spirits of our Imperial ancestors?,” Hirohito asked before stating – “we have resolved to pave the way for a grand peace for all the generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is unsufferable.”

As soon as Hirohito’s recorded message concluded, another voice followed, explaining what the Emperor had intended to say – Japan was surrendering to the Allies. The shock of the Japanese public is difficult to convey. Since the early 7th Century, Japan’s emperors had been viewed as tenshi or a “son of heaven.” While the power of the individual emperors varied, each had been a part of a 2,600 year lineage from rulers, according to Japanese legend, that descended from heaven. Thus in a brief few minutes, the people of Japan had heard for the first time from a being they were taught to view as a deity, and that message included the deity proclaiming the nation’s first defeat by a foreign power in 1,500 years.

—

The second angle of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s famous “V-J Day in Times Square” photo – only captured by photographer Victor Jorgensen. Multiple people have tried to claim an identity as one of the kissers, but most accounts have been challenged

The reaction of the Allied governments was one of cautious optimism. While the general public of the Allied powers rejoiced at the prospects that the bloodiest war in human history was finally ending, the Allies were unsure what an occupation of Japan would entail. Would elements of the military conduct a guerrilla war once Allied troops were ashore? Would the monarchy work with Allied authorities to establish a new government? After all, in the surrender address, Hirohito had brazenly described Japan’s war on America and Britain as one “out of our sincere desire to ensure Japan’s self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia, it being far from our thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement.” Could Japan be trusted to act in good faith in peace when they most certainly hadn’t in war?

There was still tremendous work – and political conflict – ahead. But on August 15th, 1945, World War II was over.

Wonderful as always. I love your WW II writing; it is my favorite topic on which you hold forth. Applause!

well done First Ringer!

Pingback: The Beginning | Shot in the Dark