For over two months, the Isonzo river had been blissfully quiet along the border of Italy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Little fighting echoed through the peaks of Mount San Michele or valleys of the Banjšice Plateau. Following Italy’s exuberant entry into the Great War the previous spring, there had been little progress in the realization of “Italia irredenta” as both sides had exhausted themselves by August of 1915. Italy’s second major offensive of the war at Isonzo had halted just months earlier for literally running out of ammunition.

Supplies would not be the hurdle for Italy on October 18. 1915. 1,200 artillery pieces and 19 divisions worth of men would hurl themselves against the rugged cliffs and the Dual Monarchy’s trenches in the third of twelve eventual attempts to break the Austrian line. For the Italian soldiers who were lead forward with cries of “Avanti!“, Isonzo would become less a war than a battle of endurance – against the elements, and Italian generalship.

—

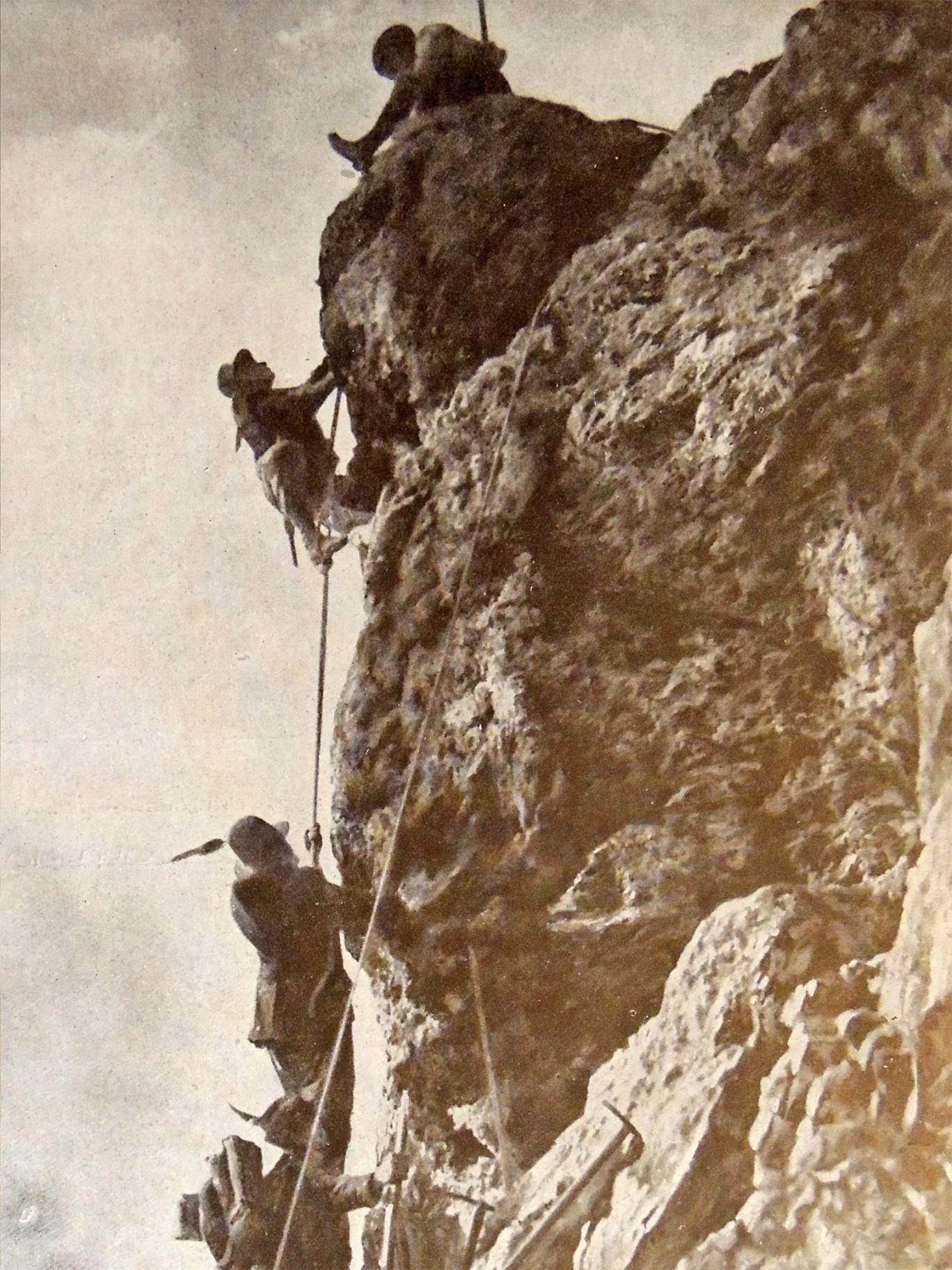

Italian light infantry of the 1st Alpini Regiment on Monte Nero, during the Isonzo campaigns

There may not have been a more difficult place on the planet to conduct a major offensive than the Isonzo river valley.

Cutting through the Julian Alps, with some mountains reaching 6,500 feet, the Isonzo (or Soča, as it’s called in Slovenia) was then as now a land of extremes. Sheer mountain faces with plunging temperatures were coupled by river valleys that easily flooded whenever there was even the slightest warming. The pictures from the front tell the story by themselves, as men vainly attempted to move forward, yet alone fight. With few navigable paths, attacking armies were forced along predictable routes, making it all the easier for any defender huddled in their trench.

Italy’s motivation for attacking at Isonzo hardly compensated for the miserable conditions under which they forced their troops to fight. The Isonzo river valley lies en route to the Ljubljana Gap – a famed meeting point between the Alps and Dinaric Alps – which if held, might have allowed Italy to strike directly towards Vienna and the heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But that was not the importance of Isonzo among the war planners in Rome. Rather, it was a pivot point towards Trieste – a wealthy coastal city and a prized goal of Italian imperial expansionists. Capturing the Ljubljana Gap might knock Austria-Hungary out of the war. Capturing Trieste absolutely would not.

—

Men were crowded into the small, narrow areas where they could camp on the mountainside. The inhospitable environment of Isonzo would later become the background of Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms”

The difference in objectives hardly mattered to Italy’s supreme commander, Gen. Luigi Cadorna.

If there was a Great War general who epitomized the various failings of the 19th Century European military model, one would be hard pressed to top Luigi Cadorna. Like most of the senior officers of his day, Cadorna was older (at 64, he was less than a year away from mandatory peace-time retirement standards) and inexperienced at actual combat (he had never seen a shot fired in anger). And like most of officers of his era, Cadorna was obsessed with Napoleonic tactics. Cadorna literally wrote the book of Italian offensive doctrine in the years before the war, and coupled with his high-rank and reputation as a stern, no-nonsense commander, Cadorna seemed the logical choice to lead.

Italian Gen. Luigi Cadorna. His generalship would break the Italian army in 1917, nearly costing Italy the war. His punishment? He wound up at Versailles, counseling the larger Entente war effort

At Isonzo, Cadorna would transform his reputation from a knowledgable tactician to “one of the most callous and incompetent of [the] First World War commanders.” During his time in command, Cadorna dismissed no less than 216 generals, 255 colonels and 355 battalion commanders. His disciplinary measures on the enlisted men were no less harsh with one out of every 17 men being brought up on charges during his tenure. And while other Entente nations struggled with discipline as a result of ordering waves of men into fruitless assaults, Cadorna believed he had a simple solution – reviving the Roman practice of decimation; the killing of every tenth man in units which were accused of cowardice. 750 Italian soldiers were executed during the war – more than any other nation.

Despite the sagging morale of the Italian army, and Cadorna’s dismissive attitude towards even his superiors (he would tear up notes from Victor Emmanuel III or the Prime Minister, even in front of their representatives), no one was prepared to relieve Cadorna of command.

—

Svetozar Boroevic – the “Knight of Isonzo.” A Croat, Boroevic would become a Field Marshal and one of the most prominent generals the Dual Monarchy produced

Across the mountainous no-man’s-land at Isonzo in the Austro-Hungarian camp was Cadorna’s opposite in almost every facet.

Svetozar Boroević would emerge from the Great War as perhaps the most prominent and well-respected general in the dying Austro-Hungarian Empire. Where Cadorna came from a well-off, and well-regarded military family, Boroević’s father was a simple border guard. Where Cadorna viewed himself as a teacher of the offensive, Boroević was a master of the defensive. And where Cadorna was despised by his fellow Italians, Boroević was embraced across the various ethnic lines that were quickly dividing his nation. A Croatian, Boroević preferred to be identified by his nationality, causing several ethnic groups in the Empire to embrace him as their own. To his men, he was Naš Sveto! (“Our Sveto!”). To the Empire, Boroević was about to become the “Knight of Isonzo.”

—

Italian soldiers attempt to advance. Nature, not the Austrians, was often the greatest adversary

The Third Battle of Isonzo proceeded like almost every battle in the region – a heavy Italian artillery barrage followed by a massive frontal assault. Cadorna, having learned nothing from the first two battles, had already decided that the lack of Italian advancement (Italy had gained 1 mile of Austrian territory by October of 1915) could be easily fixed by more shelling and more punishment of his own men. In response, Boroević only had his men dig deeper trenches. As a result, Cadorna’s bravado only resulted in another 67,000 Italian casualties for no territorial gain.

Cadorna barely waited two weeks before restarting the offensive – a fourth Battle of Isonzo. This time, at least, he could claim some success as the fortress of Gorizia – the focal point of the Austro-Hungarian defense – was now in sight. It was a view purchased at the expense of 173,000 Italians (and 129,000 Austrians) since June of 1915.

With winter setting in, and supplies thin for both sides, an informal truce was reached in December of 1915. Isonzo had bled both sides white, but only the Austro-Hungarians could plausible reach for help. Despite the fact that Italy wasn’t officially at war with Germany, and wouldn’t be until the spring of 1916, Vienna began courting German help on the Italian front. It would be nearly two years later when German troops would arrive en masse at Isonzo, but their presence would produce the 12th and final battle of that horrid front in 1917.

Pingback: The Strafexpedition | Shot in the Dark