Thousands of curious spectators had gathered along the Rue du Rhône in Geneva at 11am, watching in earnest as the Swiss Federal Council and the State Council of the Canton of Geneva marched in slow procession, escorted by a small military contingent. At their forefront, Swiss President Giuseppe Motta basked in the adoration of the crowd as the parade of Swiss dignitaries entered the giant Salle de la Réformation event center.

Inside, a collection of 241 delegates from 41 member nations (minus Honduras, whose delegation was still traveling), waited for Motta to take his seat as a honorary chairman at the dais. The Acting President of the Assembly, Belgian politician Paul Hymans, rang a bell at 11:16am and declared the meeting open – the first official meeting of the League of Nations had begun on November 15th, 1920.

It had been a long and circuitous path to get to this day and the League’s first moments in formal existence (technically, the body had been organized in January of 1920 and had met in it’s proto form), exposed the flaws in it’s creation. As League drafted a message of thanks to American President Woodrow Wilson, stating that they had gathered on this day at the American’s request, the United States was absent from the proceedings, as well as the Soviet Union, Germany and roughly another 44 sovereign nations that had either been excluded or had chosen to bypass the organization. And the debates of the first day proved how fragile the newfound League could be, as France threatened to withdraw within hours when the subject of Germany’s admission was discussed.

In the air of the combative and disorganized proceedings, the ultimately prophetic words of Woodrow Wilson to the assembly could be heard: “I can predict with absolute certainty that within another generation there will be another world war if the nations of the world do not concert the method by which to prevent it.”

/leagueofnations-7e9e88fdfb5240a9b3cf08eeda8d3fd1.png)

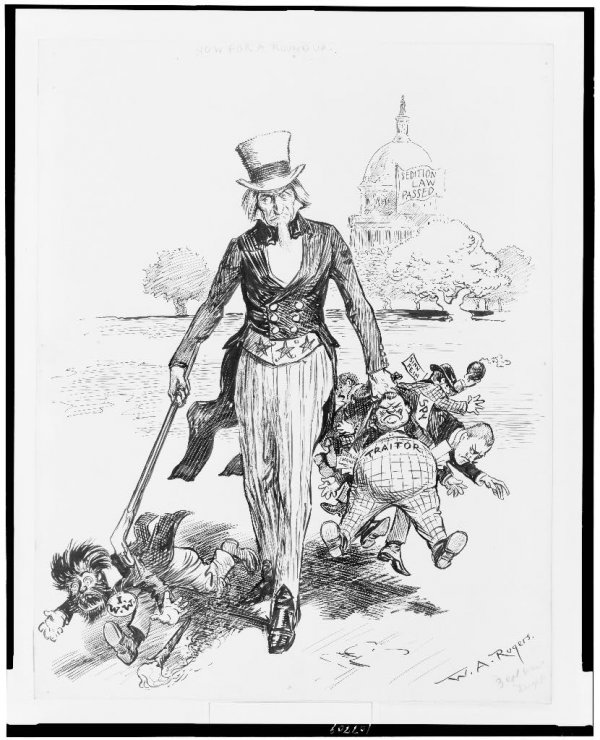

The first meeting of the League of Nations – deep divides on policy could be seen from the literal first minutes of the organization

Depending upon one’s historical perspective, the events of November 15th, 1920 in Geneva either represented the end of a nearly 150 year path of diplomatic and small ‘r’ republican political progress or a revolutionary jump from nation states, to competing alliances, to finally a burgeoning sense of global, collective action. The difference in historical narrative would eventually define those who chose to participate versus those who didn’t, and color the very notion of the purpose and powers of the League of Nations. Continue reading