The thuds heard across the Italian line at 2am on October 24th, 1917 were not the usual sounds of artillery. No explosions followed, only the clanking sound of canisters falling from the sky. The hiss that followed was unmistakable – the release of poison gas.

The weary Italian troops in their trenches had been prepared for this eventuality and were armed with gas masks. But the front line trenches were in a valley, with no wind and fog, meaning the gas would linger on the ground. Italian troops began to panic, knowing their masks would only last a couple of hours, at most, before the chlorine-arsenic would literally melt the plastic and allow the gas into their lungs. As Italian troops attempted to retreat, the Austro-Hungarian line erupted in artillery fire, striking down entire units. German mountain troops, armed with the new more portable 08/15 Maxim machine gun and flamethrowers stormed the Italian trenches, improving upon the same tactics the Germans had first experimented with at Verdun. The Italians were overwhelmed.

Near the Slovenian town of Caporetto, the Italian army would be dealt one of the most decisive blows in the entire Great War. The military and political effect would alter the strategy of the entire Entente and leave scars on the Italian psyche that persist to the modern age.

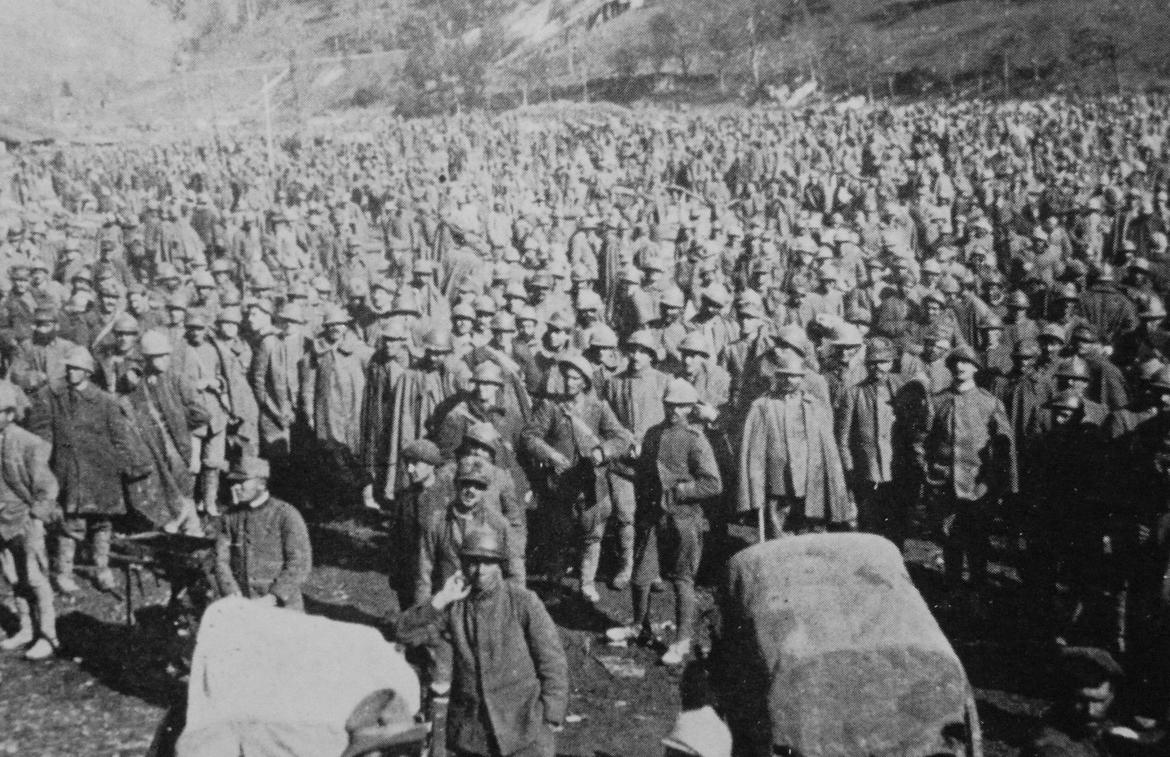

Italian prisoners at Caporetto – it was one of the largest surrenders in Italian military history

With modest exceptions, the Italian front had largely stayed the same since Italy’s entry into the war in the spring of 1915.

Despite achieving a relative breakthrough at the Sixth Battle of Isonzo in the late summer of 1916, Italian forces had again found themselves deadlocked against the mountainous front lines of the Austro-Hungarians. In offensive after offensive, the Italian army either gained no ground or made minor gains for equal or greater casualties than their Austro-Hungarian opponent. By the summer of 1917, the reality of the Italian front had become painfully clear to both the Allies and Central Powers – changing the status quo would likely require outside intervention. The only question was which side would accept their ally’s help first?

Italy appeared unlikely to ask – or receive – assistance. Since the victory of Sixth Isonzo, Italy’s Chief of Staff, Luigi Cadorna, had made himself all but immune from political consequences. While Cadorna was despised by his men – he had reintroduced the concept of decimation, the random execution of 1 in 10 men for units accused of cowardice – he had also seemingly fired anyone would could have represented a threat to his rank. By the end of his service, Cadorna would sack 217 generals, 255 colonels and 355 battalion commanders. No one in Italy, in government or in the military, seemed willing to challenge his increasingly callous and ineffective orders.

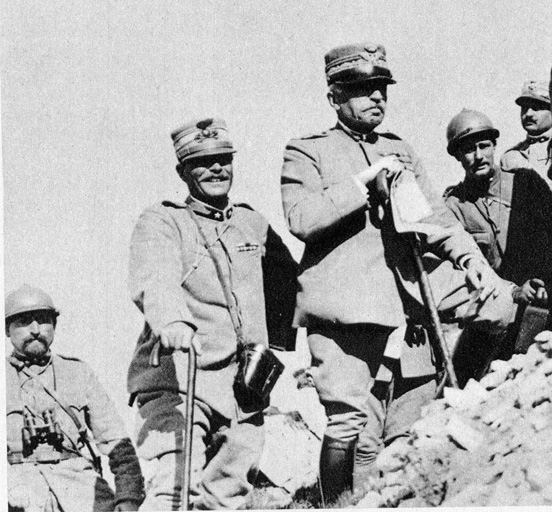

A young Erwin Rommel (right) – Rommel’s battalion of 150 men captured 150 guns and 9,000 Italian soldiers for 36 total casualties. He was awarded the Pour le Mérite for his actions

But it was a political change in London, not Rome, that brought about the possibility of the Allies providing more help to the Italian front. Eager to circumvent the Western Front, David Lloyd George looked to double-down on Britain’s obsession with secondary fronts. Beyond George’s eventual “Jerusalem by Christmas” order to his generals, the new British PM believed that by providing aid to the Italians, the Allies could “knock the props out” from under the Central Powers. With the Ottomans and Austro-Hungarians out of the fight, Germany would not chose to continue alone, or so George and others believed.

Despite significant pushback from his generals, the idea of moving British and French troops to Italy was beginning to gain traction. As if on cue, the Italians began to gain ground at Isonzo. At the Tenth and Eleventh Battles, Italian forces battered the Austro-Hungarians, gaining territory and racking up enemy casualties. With France dealing with mutiny and Britain bleeding out in Flanders, not only did the Allies determine they hadn’t the manpower to spare, but that the Italians no longer needed the help.

The Austro-Hungarians had fewer qualms about accepting Germany’s aid – and likely less of an ability to say no. Since the twin disasters of Asiago and the Brusilov Offensive in the summer of 1916, the Austro-Hungarian war effort had increasingly been dictated from Berlin. The polygot empire appeared ready to end the war – indeed, it’s newer ruler Charles I was attempting to do so – and without German reinforcements, would almost certainly collapse.

The peaks around Isonzo – the terrain was one of the worst areas in the world to conduct an offensive operation

The German contribution to the Italian front appeared more as the result of political pressure than a significant military investment. Only six divisions, part of a remade 14th Army with Austro-Hungarian units, would arrive. And while these troops would be elite mountain soldiers, commanded in one battalion by a young Erwin Rommel, Italian intelligence assumed little would change. The Italian army still vastly outnumbered the Austro-Hungarians, and with so few men to spare, Vienna could ill afford a costly offensive. Nevertheless, Cadorna displayed uncharacteristic foresight, telling his divisional commanders to assume a defensive position. Unfortunately, Cadorna, who literally wrote the book on Italian offensive tactics, knew little about how to go on the defensive, providing no details to his subordinates as to what defensive positions to take. No one wanted to incur his wrath by asking for details.

By the fall of 1917, Italy looked to be in the strongest position of the war thus far. They had no idea what was about to unfold.

Gen. Luigi Cadorna (center right) – called “the most callous commander of the First World War” by historians, Cadorna was politically untouchable due to his few victories and the low standing of his civilian authorities

The combination of poison gas, stormtroopers and targeted artillery bursts tore open the center of the Italian line, with the Germans advancing 16 miles on the first day.

Despite being outnumbered at Isonzo 350,000 soldiers to 874,000, Germany’s infiltration tactics quickly evened the odds. Much like he would do with armored units a generation later, Rommel and his mountain shock troops would bypass enemy trenches and fortifications, preferring to strike behind the line, sowing seeds of chaos that would cause the collapse of units at the front. The Italians would only make the situation worse by adopting the same hardline stance they had at Asiago, wrongly believing that their “to the last man” strategy had won that battle, rather than Austria-Hungary’s need to send men to the east to deal with the Brusilov Offensive. Cadorna had won his reputation with his defensive stand at Asiago – he believed he could recreate the situation if only he remained rigid enough in his tactics.

Cadorna simply moved units from other places on the Isonzo front to try and block the German advance. The result left more gaps in the front line that the rest of the Austro-Hungarian army dashed to exploit. Within days it had become clear to everyone, except Cadorna, that the entire Italian line was in danger of being overrun. A week after the offensive began, Cadorna finally relented and ordered a general retreat. It was too late. 1.5 million Italian soldiers began the process of retreating and the ensuing chaos would cost them an entire army.

Italian supplies left behind – it wasn’t merely men that Italy abandoned at Caporetto

The Italian 2nd, 3rd and 4th armies were all in danger of being overrun by the Central Powers and all three were trying to use the same limited number of roads and bridges to retreat. Cadorna’s callous nature was perhaps finally put to good use – either he could try to save all three armies and potentially lose all three, or sacrifice one and keep the remainder of the Italian army ready to fight another day. Cadorna chose the 2nd Army, which had already suffered the brunt of the action, to be the group that would fall on the sword. 285,000 men, the majority of them from the 2nd Army, would surrender at Caporetto. Within days, the number of divisions in the Italian army was literally cut in two. But the 2nd and 3rd armies survived with most of their men and equipment – Italy had suffered a humiliating defeat, but could have emerged without any army at all.

If not for the lack of food and supplies, the German-led offensive might have continued. Rommel would later note that asking men to march all night and fight all day on empty stomachs was a fool’s errand. Nevertheless, the offensive had gained nearly 100 miles, and would inflict 305,000 casualties while capturing over 3,000 pieces of heavy artillery. The Italian army had, for all intents and purposes, been gutted.

The territorial scale of Caporetto – for a conflict that measured victory in meters, not miles, Caporetto represented territorial losses the equivalent or greater than some World War II battles

The shock of Caporetto filtered throughout Italy and entire Allied cause. But the search for answers would take a secondary role to the search for scapegoats.

Cadorna and others blamed the average Italian soldier. Reports of desertion during and after Caporetto became common, but as many Italian troops attested, they had been informed the war must have been over following such a decisive defeat and headed home. With the Italian command scattered – Cadorna kept moving his command headquarters and didn’t stay in communication with his generals – there were few officers in place to keep unit organized. Cadorna’s excuses were not enough to save his position and the one of the worst generals in the entire Great War was finally relieved of command.

Others saw meta-level rationalizations for the defeat. Nationalist (and later Fascist) poet Gabriele D’Annunzio remarked: “Italians want a greater Italy, by conquest not by purchase, not shamefully but through blood and glory,” blaming socialist influence on the defeats. The Socialists themselves declared the defeat represented a “soldier’s strike” against the war. All agreed Caporetto represented “the greatest defeat in Italian military history.” The term would later become shorthand for any folly, even into the 21st Century.

Italian anti-war propaganda – Caporetto remains a dirty word to this day

For the Allies, Caporetto represented the worst case scenario from the absence of inter-allied cooperation. While the Inter-Allied Conferences at Chantilly had outlined some strategy of coordination, the end result had largely been Britain and France holding leverage over the Italians and Russians to launch offensives to distract the Central Powers. For David Lloyd George, averting another Caporetto required a Supreme War Council of all the Allied powers – and eventually a Supreme War Commander.

Is it racist if my love of soul music is ironic? Like a hypstr’s love of 60s polka music?

Sorry, wrong thread!

But well done nevertheless, First Ringer!

Pingback: In The Mailbox: 08.17.18 : The Other McCain

Pingback: The Kaiser’s Battle: Part One | Shot in the Dark