The term “arms race” is almost – sort of – falling into disuse these days.

I’m sure it won’t last forever.

Those of us of a certain age well remember the ultimate arms race – the race to build nukes between the US, the USSR, China, and their various proxies and allies in the Cold War. The goal of that arms race – it almost seems counterintuitive – was to build weapons that’d deter their use by others. So far so good.

It wasn’t the first arms race. Far from it.

But 100 years ago today, one of the history’s biggest, most expensive arms races was coming to a violent, explosive, and yet fitful and indecisive conlusion in the chilly waters of the North Sea.

And along with the arms themselves, and the men who worked them, other things were being weighed and found wanting; grand strategies, and the the technocrats who conceived them.

Brittania Rules The Waves: In 1588, an armada from Spain attempted an invasion of England; the fledgling Royal Navy defeated and scattered it. It was the kind of victory that launches – and did, indeed, launch – myths and legends around which nations build themselves.

And indeed, that’s what happened; for the next 350 years, the Royal Navy thwarted every attempt to invade Britain, and eventually became the glue that held together the British Empire, the tarp that’d smother any brushfires that might break out, and the shield that kept it safe from any who’d dare try to bite off a chunk.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 set the pattern for the next century; the British Navy, with no rivals anywhere on the planet, was in effect the world’s beat cop; with it, the British Army – highly professional by the standards of the day, and extremely small for the world’s dominant superpower – could be carried to the scene of the Empire’s countless little brushfire wars in safety, to fight with the aid of colonists, mercenaries and proxies to put down the insurrection.

At the twilight of the Age of Sail, as the technology of the iron cannon and the sail-powered ship drew to a close, the Royal Navy dominated territory that made Alexander and Rome’s legions green with envy.

Disruption: Marketing weasels today are fond of talking about “disruptive innovation”. And 21st century westerners are often of the conceit that we, here and now, live in an era of unparalleled disruption.

But the world between 1815 and 1865 went through a spasm of technological, cultural and social revolutions that were in many ways the underpinning of our entire world today (and I strongly recommend Paul Johnson’s The Birth Of the Modern to go into them in wondrous depth); from trousers (yes, a revolutionary development) to the consumer piano to the steam and internal combustion engines to the notion of serious art to the idea of direct election of representatives to the asphalt road to the to the rise of Social government to Edinburgh Renaissance to the mechanical analog computer, the age was perhaps the most amazing in history.

Several of those disruptions brought changes that threatened to completely disrupt the world order – indeed, some of them led to the changes that brought about World War I in the first place.

- The rise of the European nation-state, replacing the dog’s breakfast of duchies and kingdoms with large, centrally organized nation-states. Joining France (regaining strength in the century after Napoleon) and the Austro-Hungarian Empire (a weak “empire” whose energy largely went to trying to keep its myriad ethnic factions playing nice) were Italy, in a position to dominate the Mediterranean, and most of all Germany – industrious, industrial, culturally homogenous, and governed by a militaristic semi-constitutional monarchy nominally under a Kaiser but governed mostly by an authoritarian, militaristic bureaucracy, the new Germany set about becoming an industrial and military power; in humblingFrance in 1871, they showed themselves a serious contender.

- The Ironclad Warship: Field-tested in the American Civil War, the armored warship instantly made the vast fleets of wooden ships – like the Royal Navy of the day – obsolete. (Not so much the steam engine; the British adopted steam with uncharacteristic speed). Suddenly, nations that had been second or third-rate powers were, for a brief moment, on an even keel with the mighty Royal Navy; for a moment in the 1860s, the Brits were genuinely worried about the fleets of France and Italy, which briefly led them in ironclad technology, a gap made up only at great expense and with immense pain.

- The Torpedo: Ultimately even more revolutionary – the effects of this invention are still with us today. Also field-tested in the Civil War, the original “torpedo” was an explosive charge on a long spar carried at the front of a small boat (as well as in front of the first submarine, the Confederate Navy’s “Hunley”). It broached the prospect that small boats could sink the mightiest battleships – a prospect made starker just after the war, when a Briton, Robert Whitehead, working in Italy and Croatian, replaced the boats that carried the spar torpedoes, putting an engine behind the explosive charge, allowing the boat to shoot the torpedo from hundreds of yards away.

- Cheap Steel: Steel had been considered an almost-exotic material through most of human history. Occurring in tiny amounts in nature, manufactured only with extreme difficulty, it was a scientific oddity and technological dream. And so through the American Civil War, most of the world’s metallurgy – especially cannon and armor – was in iron and bronze. That changed in the mid-1800s, as changes in technology made steel passably affordable and usable in the market – first for building smaller objects, like cannon, and eventually as a structural material. While the age of the wooden ship lasted from the dawn of navigation to the 1850s, the age of the iron ship was perhaps two generations. And as the world’s cannon switched from relatively soft, brittle iron to hard, durable steel, the power and range of the cannon rose exponentially – driving the ranges of cannon from hundreds of yards to, by the turn of the 20th century, the limits of visual range, heaving payloads that rose from 24-48 pounds in the 1820s to nearly a ton a century later. And to use this range and power, the final innovation became vital:

- Computing: In our 70-year-old digital age, it’s hard to remember that for over a century and a half, computers were analog; gear spins, cam rotations, and rack and pinion movements in elaborate mechanical assemblies did what 1s and 0s do in your smart phone do today.

For roughly forty years, the world’s maritime powers tinkered with each of these technologies, trying various takes on the formula for the perfect warship.

And just a little over 100 years ago, all of these innovations came together in the form of the ship that was the currency of record for naval warfare for two generations.

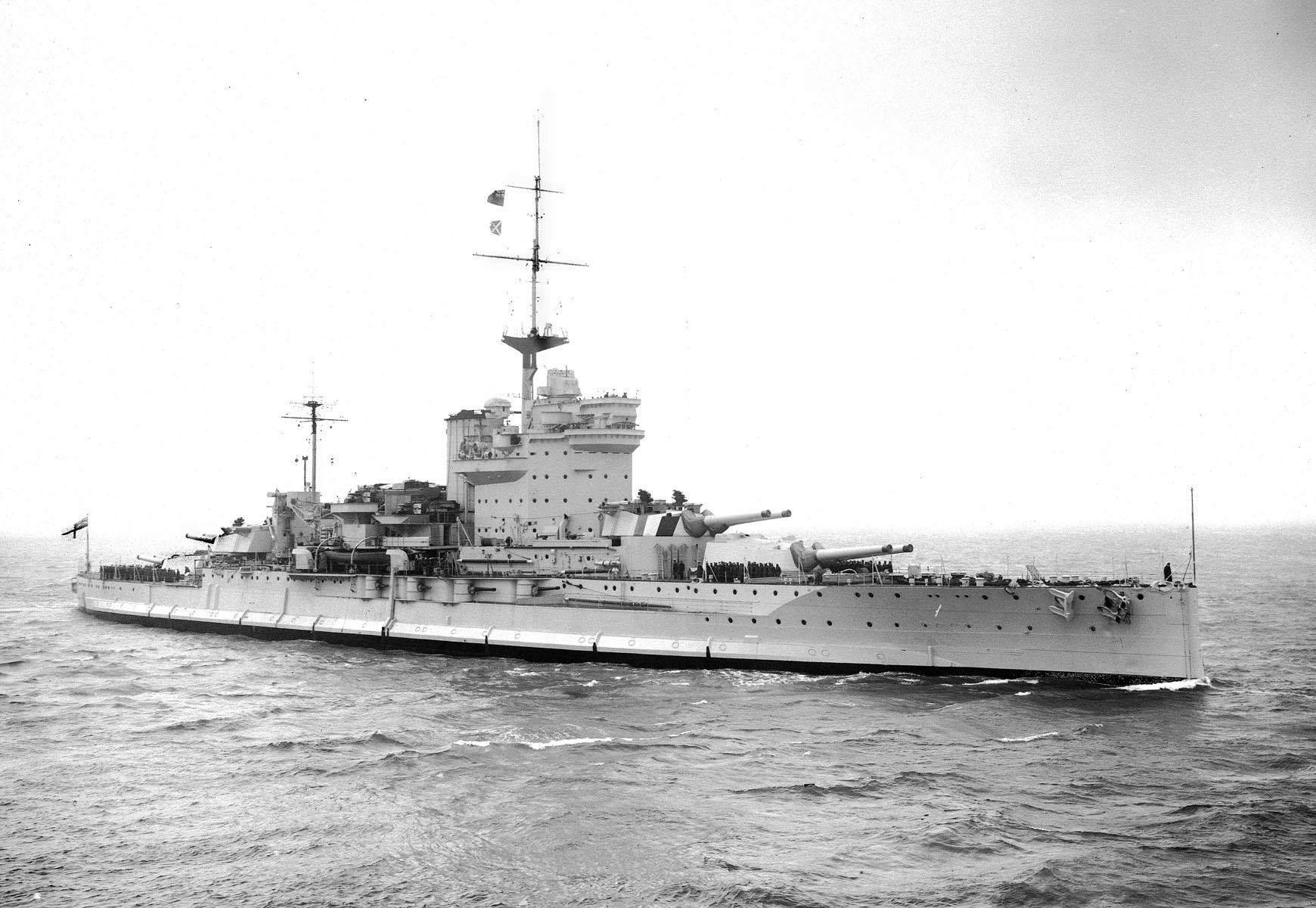

It Dreads Nought; In 1906, the British launched HMS Dreadnought – the first ship launched that tied all of these technological advances into one package, which would define what a “battleship” actually was, for the next 3-4 generations. Designed by Admiral “Jacky” Fisher – one of history’s great naval architects and thinkers, whose greatest contribution to life today may have been the invention of the term “OMG” – Dreadnought was a large, fast (by the standards of the day – 20 knots/24 mph) all-steel warship armed with a uniform battery of 12-inch guns (supplemented by a small group of 3-inch guns, intended to swat away torpedo boats), armored to withstand hits from the same-sized weapons (with special arrangements to try to negate torpedo hits); the big guns were aimed by a central mechanical fire-control “computer” that calculated a firing solution based on the Dreadnought’s speed and course, and it’s targets range, course, bearing and speed, as well as the wind, the temperature and the type of ammunition being fired, electromechanically linked to the gun and turrets, allowing the entire battery to be aimed as a single group (controlled by a fire-control crew atop the ship’s mast, with the best visibility on the entire ship), and fired by single electrical button.

Which leads us to one of the myths this series focuses on; while the world credits the British battleship HMS Dreadnought as the first ship to perfect the formula, the Japanese and Americans had similar ships on the ways; the Brits finished Dreadnought weeks before the US launched the South Carolina, ensuring that two generations of all-big-gun, turbine-powered battleships with heavy armor and centralized fire control would be called “Dreadnoughts” rather than “Southcarolinas”.

And so the technology was there. What remained was that national will to do something with it.

The Great Race: With the world’s naval calculus completely reset for the second time in fifty years, the playing field was at least briefly leveled. The world’s second-tier naval powers – France, the US, the Austro-Hungarians, Russia, Italy, and especially Japan – jumped into Dreadnought construction with both feet. Even third-tier powers – Brazil, Argentina and Chile – began acquiring “Dreadnoughts” (bought, generally, from British shipyards).

But most of all, there was Germany.

The German state, run by militarist oligarchy that co-opted a long series of historical myths to drive German expansionism, had designs on being the most powerful nation in Europe, and to building a world empire. It had gotten a fair little start – with important colonies in the Pacific, along the Chinese coast, and especially Africa.

And to make the empire viable, Germany needed a navy to protect the lines of communication between Germany and the colonies.

And while many powers – France, Austria, Italy, Russia, Japan – might conceivably take a run at a German colony, and might logically start by cutting the colony off from the Fatherland by naval action, there was only one power that could interfere with a nascent German empire, decisively and completely, anywhere in the world; Britain.

And with the playing field leveled by technology, Germany made its move. The German state embarked on a building spree unlike any other in Europe.

The British, who’d been building dreadnoughts at a brisk pace to stay ahead of similar building in Austria, Italy, France, Japan and the US, reacted by making a national priority of countering, and exceeding, German production.

And so in the 1900s and 1910s, both nations engaged in a building frenzy that strained both nations’ treasuries to the brink. Indeed, as World War I loomed, the Germans – facing the combined might of the British Navy and French Army (the British Army was deemed fairly negligible, an error that’d cost the Germans dearly in August, 1914) in the west and the immense Russian Army in the east – tried to negotiate a treaty with the Brits, guaranteeing British neutrality in a coming war, enabling Germany to dial back the hideously expensive naval building program to concentrate on the Army. The British rejected the offer – although the building program was taxing even their immense wealth.

And so by the beginning of the war, Britain had 29 dreadnought battleships (and 20 “pre-dreadnoughts”, obsolete ships from the “tinkering” era) to the Germans’ 17 (plus 12 pre-dreadnoughts). France added 10 to the Allied side; Austria-Hungary, four to the Germans’, all in the Mediterranean.

And 100 years ago today, these fleets of ships would meet their first, and only, test.

More tomorrow.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.