The flurry of telegram traffic between the various capitals of Europe in late June of 1919 was almost similar to the volume seen in the weeks before the Great War. With the fifth anniversary of that cataclysm rapidly approaching, and no formal peace treaty having yet been signed and accepted, there was burgeoning nervousness that war might return to ravage Europe. Despite months of Allied negotiations to craft terms of a final treaty with Germany, the German response had waivered between hostile rejection and begrudging acceptance. Still, no German signature had touched the treaty, in part as no German politician wished to affix their name. Chancellor Philipp Scheidemann (Friedrich Ebert had risen to the post of President of Germany with the newly announced Weimer Republic), spoke for all his colleagues when he said: “What hand should not wither that puts this fetter on itself and on us?”

The task fell upon Gustav Bauer, the next in line of authority as Schneidemann chose resignation as opposed to destroying his political legacy. Even Ebert declared the treaty’s demands “unrealizable and unbearable,” decrying not only the punitive terms but the process in which the treaty had been crafted without any input from Germany or the former Central Powers. This wasn’t a peace treaty but a division of war spoils and an unconditional surrender, or so Germany complained. Bauer cabled the Allies, stating that he would sign the treaty if a handful of articles containing language about German culpability for the war and war crimes trials for the exiled former Kaiser be removed. The Allied response was clear – sign the whole treaty within 24 hours or French troops would cross the Rhine and occupy Germany. In desperation, the new Weimer government asked Paul von HIndenburg if the German army could potentially resist a renewed Allied offensive. They likely knew the answer before even asking the question.

On June 28th, 1919, in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, 27 delegates representing 32 nations gathered to sign the final instrument of peace to end the First World War. It had been exactly five years to the date of Franz Ferdinand’s assassination. Germany had sent their Foreign Minister to oversee the signing. Gazing over the Foreign Minister as he signed was the gigantic self-portrait that Louis XIV had commissioned. The portrait’s title spoke of the Allies dominance on this day – “The King Governs By Himself.”

The treaty signing in the Hall of Mirrors – thousands of onlookers joined journalists and diplomats to oversee the brief ceremony

That any final terms of a peace treaty between Germany and the victorious Allies would be harsh could hardly have been a surprise. The process of even arriving at an Armistice had seen Germany agree to give up most of their military and infrastructure, not to mention an occupation of the Ruhr by the French that increasingly looked tantamount to annexation. Similar treaties/armistices with what remained of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires had been debilitating as well, as both empires were stripped of their territories, their infrastructure plundered and their armies legislated into irrelevance. Only post treaty/armistice violence would lessen some of the strongest terms, as the Hungarian revolution and the following Turkish War of Independence forced the Allies’ hand to renegotiate. And in the winter and spring of 1919, Germany had no appetite or ability to militarily resist.

Germany’s internal position had already been calamitous – caloric intakes for civilians were down to 1,000 a day; revolution had sporadically engulfed the country as left and right factions fought for control, and what remained of the former military and civil government was otherwise impotent to stop much. But signing the November Armistice hadn’t improved Germany’s position. The Allied blockade remained in place and the Allies refused to import foodstuffs until Germany relinquished the remains of her fleet, including her otherwise shelved merchant marine. The Germans had agreed, in principle, to surrender these ships, albeit with the understanding that the move would coincide with the end of the blockade, allowing Germany to once again engage in trade. Instead, the Allies promised to deliver food to Germany if the ships were received, and would keep the blockade in place. In the roughly five months between the Armistice and the eventual German surrender of their navy, an estimated 100,000 Germans died of starvation. Coupled with the loss of most of their railway infrastructure and crippling post-war inflation, Germany couldn’t even move or feed itself, let alone fight. And what was left of the German army was largely melting away as soldiers simply gave up their posts, ignoring orders to return back to civilian life.

It was precisely the outcome that the Allies – or more specifically – France, wanted to see. We’ve discussed before the gaping scar the Great War left on the French psyche. Nearly 2 out of every 3 French soldiers who served were either killed, wounded or captured. The defining slaughter of the war at Verdun had seen 78% of the entire French army pass through those horrendous trenches. 1.3 million French soldiers were dead; 25% of the entire male population of the country, aged 18-30. 400,000 civilians had died as well and with them, the industrial north of the country had been gutted by the German occupation, not just by conflict but by the Germans destroying infrastructure in their retreat and forcibly moving French civilians behind German lines to act as borderline slave labor. France didn’t simply want to ensure their protection against another German invasion, but to permanently break Germany’s military and economic dominance. Or in the words of negotiator and British economist John Maynard Keynes, “set the clock back [to 1870].”

While Britain certainly also pushed for a tough peace in certain areas, the French desire to permanently break the former Central Powers dominated the peace talks

Such French desires ran contrary to the wishes of her biggest allies in Britain and America. Neither David Lloyd George or Woodrow Wilson thought a punitive peace was in the long-term interest of Europe or the world, although George campaigned vigorously on such a punitive final peace in the immediate British election following the Armistice in 1918. George and his war-time coalition had been re-elected under the slogans of squeezing the Germans “’til the pips squeak” while privately declaring that any economic recovery would be impossible if Germany couldn’t revive her role as a major industrial and trading partner. And, despite the Anglo-French Entente, British interests in Europe remained constant – no singular continental power should dominate. Pre-1870, the British fear was that the dominant continental power was France, hence Britain’s alliances with various German states. Post 1870, with the rise of a united Germany, Britain now wished to use France as a counterweight. Returning to a pre-unification dynamic would inevitably make France a competitor again, potentially even an opponent. George had no interest in returning to a Napoleonic Era mindset nor surrendering Britain’s role as the power broker of Europe, keeping the continent from uniting against London.

The American position, or perhaps more specifically the position of Woodrow Wilson, went even further than Britain in terms of wanting to avoid a punitive peace treaty with Germany. Wilson had arrived in France in late 1918 to great acclaim, touting his Fourteen Points and proposed “League of Nations” as the pathway to a lasting peace treaty. If George wanted to avoid an overly harsh peace with Germany out of practicality, Wilson viewed any final peace through both his critique of the pre-war system of competing alliances and the prism of his Presbyterian idealism. The “Fourteen Points” had arrived at a critical junction of the war, as the Allies sought to justify the immense sacrifice of their peoples and counter Bolshevik propaganda that peace could only be achieved by violently overthrowing the system. But if taken literally, Wilson’s Fourteen Points represented a clear challenge to both British and French power. Self-determination of colonies, armaments reductions, and a League of Nations that could give tiny nation states the same authority and power as global empires could only hinder the post-war power and influence of the Entente. While Wilson blamed the war on Germany and was more than willing to carve up the finances and territories of the Central Powers, the American President’s post-war vision was that would be no return to a pre-World War status quo.

The question awaiting the delegates in Paris was which agenda would prevail.

The “Big Four” – David Lloyd George of Great Britain, Vittorio Orlando of Italy, Georges Clemenceau of France, and Woodrow Wilson of the United States

If the terms of the treaty were up to a popular vote, it would appear that Woodrow Wilson and the American position would win in a landslide. As Wilson arrived in December of 1918, throngs of Parisians lined the Arc de Triomphe to welcome him – no other visiting Allied leader could come close to Wilson’s reception among the French, even as most knew of Wilson’s relatively more lenient stance towards Berlin. Given the appeals from the Central Powers in the war’s closing weeks, and Wilson’s own prominence, it could have been assumed by onlookers that Wilson might be in charge of conducting the negotiations. In truth, Wilson was more popular among Europe’s populace than at home (and definitely more popular than among his foreign political contemporaries). Wilson’s Democrats had just lost the 1918 elections, losing 4 governorships, 25 congressional seats and 6 Senate races, the latter resulting in Republican control of the Senate for the first time since 1910. Now faced with an adversarial Senate at home (albeit one that wouldn’t take office until the new year), Wilson vacillated between working with or against the thin GOP majority. Wilson had been advised to bring aboard Elihu Root, the former McKinley/Roosevelt era Secretary of War as an olive branch to the Senate. Root had been a rumored 1916 presidential candidate and a leader of the “Preparedness” Movement that had criticized Wilson for his foreign policy positions. Wilson had worked with Root previously during the war, sending him to Russia to engage with the Provisional Government and apparently took his advice on the matter. It didn’t hurt that Root had been a Senator as recently as 1915, and still had significant relationships within the Chamber. But Wilson rescinded the offer, now calling Root a “reactionary” who would somehow tank the negotiations, even as Root supported Wilson’s primary goal of the League of Nations. The Senate – and Root – took notice, and when it came time to vote on the League of Nations in the Senate much later, Root opposed Wilson’s version of the organization.

While the terms of any peace treaty weren’t going to be decided in a popular vote, the immediate question was whose votes were going to matter in negotiations? 27 countries had sent delegates to Paris, with over 70 attendees to start. In all, over 30 countries would eventually take part in the Paris Peace Conference – but not one of them were from the defeated powers. The initial talks at the Salle de l’Horloge in the French Foreign Ministry could barely contain the full delegations, nor could the process endure if every measure had to passed by a majority of the participants. Did economic terms between France and Germany need to be approved by nations like Panama and Liberia?

The “solution” was narrowing down the Conference to a so-called “Council of Ten”, consisting of two delegates each from the United States, Britain, France, Italy and Japan – the “Big Five” of the Allied powers (Russia had been excluded from talks having signed a separate peace with Germany, in addition to their communist pariah status). Eventually, the Council of Ten became the Council of Five, as each of the major nations assigned their own foreign ministers to continue negotiations. Even this arrangement slowly disintegrated into a “Big Four”, largely excluding Japan, while Italy remained technically on the inside of negotiations, but found their objectives increasingly ignored by the “Big Three” Allied powers.

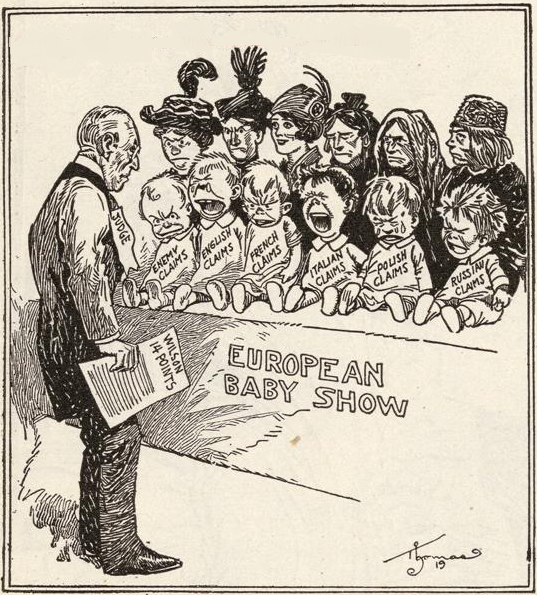

Even pro-Wilson publications depicted the European powers as children in the negotiation process. Such images, although intended to make Wilson the adult in the room, likely contributed to American resistance to the final treaty and the League of Nations

Such a structure may have fit in with the realpolitik of European affairs before the war, but by design left a number of Allied partners out of the process as the map of the world was being reshaped largely without their input. At it’s core, the Conference was laying bare the shifting promises the Allies had made over the years in order to entice nations to join the war effort, and the fundamental difference in values that held propelled them from the start of the war versus the end. The Entente of 1914-16 had been interested in largely dividing up the spoils of war, from Germany’s various colonies to the Ottoman Empire. The Allies of 1917-18 had ostensibly fought for self-determination and an equitable peace, however one truly wished to define such a lofty principle. Sometimes those values could overlap, as supporting the Arab Revolt satisfied some of the territorial goals of Sharif Hussein bin Ali while also granting Arabs a measure of self-rule. More often they conflicted, as the promises made to Yugoslavia ran contrary to promises made to Italy; or territory promised to China would go to Japan. In either event, the process was already frustrating the attendees, especially as numerous sub-committees would form in response to complaints, meeting repeatedly only to see their recommendations ignored while literally a handful of men decided the future of the world.

All Germany could do was watch from afar. The view from Berlin was knowing that a terrible price-tag likely awaited any final treaty, but with the assumption that there might be some level of negotiation. Instead, Germany was given an early draft of the final treaty in May of 1919 and were horrified by the contents.

Germany would lose 25,000 square miles of her pre-war territory, including concessions to France, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Poland and even Denmark (who hadn’t participated in the war). Eastern Prussia would find itself divided from Germany proper, with the Danzig corridor separating them to allow Poland access to a port city. Regions like the Saar would be under French occupation, with the industrial output given to the French government for the next 15 years until a plebiscite would determine whether or not the region would permanently leave Germany. Seven million ethnic Germans would be placed into other nations. The army would be reduced to 100,000 men and could not own or produce armored cars, tanks or aircraft. The final bill for reparations had yet to be determined, but until the Allies came up with an estimate, Germany would owe $5 billion USD (at 1919 prices). By 1921, the Allies estimated the final total to be $132 billion gold marks ($269 billion USD now), of which Germany would find itself paying $500 million USD annually, plus 26% of all German exports. It was a debt Germany couldn’t possibly hope to repay without gutting their economy.

German children suffering from starvation. An estimated 763,000 Germans died of lack of nutrition/food during the entire war

Within less than two years of being handed the final butcher’s bill for the First World War, reparations and the terms of the post-war settlement pushed Germany into hyperinflation. 42 billion marks were the equivalent of one U.S. cent in late 1923. In short, Germany had nothing of it’s own left to produce. It’s infrastructure had been given to France and it’s industrial sector’s output filled French coffers. In response, workers in the Ruhr went on strike, refusing to produce goods that they couldn’t profit from (the German government was now directly paying the workers, not the factories nor the French). The Weimar Republic now looked completely hapless to the German public – they had saddled Germany with post-war responsibility for the conflict, a nearly unpayable debt, and crushing inflation. It was little wondered then in late 1923 that a public rally for the Bavarian government in a Munich beer hall, Erich Ludendorff reappeared from self-exile along with members of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party and declared their seizure of power. Marching the next morning in downtown Munich in an attempt to build popular support for their quasi-coup, Ludendorff, the Nazis, and their leader, Adolf Hitler, were confronted by police. Within a minute, shots were fired and 16 Nazis lay dead. Ludendorff and Hitler were arrested, only to have Ludendorff acquitted of charges of treason and Hitler given a minor sentence.

The Weimar Republic would be given some reprieve as the Allies could see that the scale of the reparations being asked of Berlin were simply unachievable. The Allied Reparation Committee met again, chaired by American banker Charles G. Dawes. It was determined that Germany’s war debt would be significantly reduced and that the Ruhr would be returned to Germany to help them finance their debts and kickstart their economy. The U.S. would essentially lend Germany it’s interest payments for reparations while helping to recapitalize Germany’s central bank. The resulting “Dawes Plan” would help curb hyperinflation and launch a German economic recovery until the Great Depression. For his efforts, Dawes would win the Nobel Peace Prize and end up Vice President under Calvin Coolidge.

No one left Versailles satisfied with the outcome – and few left with any rationalization that they had laid the bedrock for a lasting peace. John Maynard Keynes mockingly called Versailles a “Carthaginian peace” – referencing the harsh terms Rome had placed on Carthage which eventually prompted the Third Punic War which required burning Carthage to the ground in order to end the fighting. Marshal Ferdinand Foch came at the situation from the opposite angle – he felt the treaty was too kind to Germany – but ended up with the same analysis: “This is not a peace. It is an armistice for twenty years!”

Germans protest Versailles

But was Versailles unduly harsh and did it directly lead to the Second World War? The interwar answer to both questions was largely “yes”, as it became clear to future Allied governments that the economic and territorial concessions of Versailles hindered Germany’s economic recovery and fostered irredentist claims from even moderate German politicians, to say nothing of the Nazis who followed them.

Yet in many ways, Versailles was not as punitive as similar treaties from the era nor as economically crippling as the narrative suggests. The Central Powers’ Treaty of Brest-Litovsk against Russia was lenient only in the economic sense that the Central Powers knew Russia didn’t have much in terms of hard capital to hand over in any settlement. Russia was forced to pay “only” 300 million gold marks, but lost 30% of it’s pre-war territory. Within that territory was 34% of its population, 54% of its industrial land, 89% of its coalfields, and 26% of its railways. Germany and her allies didn’t need capital; they had essentially seized Russia’s entire means of production for themselves while breaking apart the various provinces of the Tsarist Empire. A similar Allied treaty could have empowered the numerous states of Germany to undo unification, giving the 22 “federal princes” their kingdoms back. But even France knew that the various German states were too weak and their princes too unpopular to fully break apart Germany without significant and lasting foreign occupation. And while losing lands with German populations would become a core tenant of early Nazi propaganda, many of those seven million ethnic Germans separated from the homeland had left long before the next world war – unfortunately partially due to repression and watered-down ethnic cleansing by their new governments.

The argument that Versailles was economically punitive is relatively stronger given that the Allies changed the terms of German reparations and the United States was willing to grant loans to help finance payments. A significant recession followed the Great War, largely as it became clear that a war economy was unsustainable and that no giant new sources of capital would be available to repair the economic damage the war had wrought. It didn’t help that a number of new nations born out of the war tried to boost their coffers by issuing high tariffs, further reducing post-war trade. But these factors and reparations didn’t prevent the Weimar Republic from joining in the rest of the world in seeing rapid economic growth in the mid to late 1920s. By 1929, Germany’s GDP was higher that it had been in 1913 and their exports had more than doubled by comparison to pre-war figures. It was little wonder then that this era was called the “Golden Age” of the Weimar Republic.

The Munich Beer Hall conspirators

In many cases, the most controversial aspects of Versailles were abandoned long before the rise to power of the Nazi Party. There were no real war crime tribunals (a few cases produced minor sentences) and even Kaiser Wilhelm II escaped any sort of trial as Holland refused to extradite him, fearful that Wilhelm II might be executed (David Lloyd George had publicly called for the Kaiser to be hung). Germany was admitted into the League of Nations (more on that debacle later) over the strenuous objections of the French who hoped to keep Berlin ostracized from the world community, and largely saw rapprochement with Europe during the Weimar years. The Allies, and the world at large, had no stomach to enforce those terms of Versailles that might have done more to keep the peace. German rearmament was well known as early as 1929 as German journalist and pacifist Carl von Ossietzky publicly exposed Weimar’s military relationship with the Soviet Union where the Soviets were secretly arming and training German units, all against the clauses of Versailles. The Allies did nothing in response.

Versailles did not ease the transition from the pre to post war world but neither did it guarantee that Europe would have to engage in another global conflict. If the question at the start of the Peace Paris Conference was which nation’s agenda would “win” the peace talks, the simple answer is none of them did. Britain and France wanted a return to some version of the pre-war period; instead the post-war world started the process of eating away at their economic, military and colonial power. The United States wanted a radical reinterpretation of global order based around collective security; instead a power structure led by the major powers who had started the war remained. The world’s minor independent nations wanted a seat at the table of global decisions; instead, they were given largely powerless seats within the great power dominated League of Nations. And lastly, late 19th century new powers like Italy and Japan wanted to achieve great power status by the same tactics the larger powers had used – colonialism and conquest. Instead, they felt the “rules” of acceptable international relations had been changed to block their ascent and codified into law by the series of arms treaties in the post-war period.

With no power or coalition getting precisely what they wanted out of Versailles, the motivation to defend what had been created by it dissipated quickly. For in the end, Versailles had not provided what all parties had truly hoped for – a rationalization for the sacrifices of the Great War.

The Douaumont Ossuary – a French memorial containing the skeletal remains of soldiers who died on the battlefield during the Battle of Verdun in World War I

When I was in the Hall of Mirrors I thought of just that signing event, and tried to imagine all those people crowded in there…

So post World War One, leaders decided the cause of the war was unresolvable conflict between those prison houses of nations called empires.

So they dismantled the empires and promoted nationalism. They even created a league of nations to resolve conflicts and pursue common goals! Nationalism was the future!

And nationalism became the cause of the even more disastrous and murderous World War Two.

If there is a World War Three, the cause of it will be some hare brained political scheme that originated in Europe.

Plus ça change, plus ça reste pareil