As the German Spring Offensive raged on the ground, so to did the action in the air on April 21st, 1918. Above the Somme, as German forces drove relentlessly into the British line, a handful of German and British aircraft dueled for air superiority. A young Canadian pilot, Lieutenant Wilfrid “Wop” May, had fired a few bursts from his machine gun at one of the Germans. The German evaded his shots and May quickly noticed a distinctive red, Fokker Dr.I triplane begin to chase him. This was May’s only second day in combat and he immediately knew he was being pursued by arguably the most famous pilot in the world, Manfred von Richthofen – the “Red Baron.”

May fled as quickly as he could back into British territory, knowing full well he stood little chance against the German ace credited with 80 aerial victories. Richthofen normally would have broken off the pursuit – he had always told his fellow pilots not to overzealously follow a single target – but May had fired upon Richthofen’s cousin and the “Red Baron” appeared out for blood. May’s friend, Captain Arthur “Roy” Brown, saw his fellow Canadian airman was in trouble, and despite the long odds against winning, engaged the German. In the cluster of gunfire from planes, and anti-aircraft rounds from the ground, Richthofen was struck – a bullet tearing open his chest. But his aircraft seemingly managed a rocky landing behind the British line before finally crashing against trees. Nearby Australian troops rushed to see what they could find. Richthofen had smashed himself against the butt of his machine gun and flight controls. He had likely died before even fully landing his plane.

The man that Erich Ludendorff had said “was worth as much to us as three divisions” and had terrified Allied airmen was no more.

Manfred von Richthofen – the Red Baron. With 80 confirmed victories, Richthofen was the winningest pilot of the Great War. The next highest was French pilot Rene Fonck with 75. 20 confirmed victories were required to be viewed as an “ace”

One of the more notable quotes in film history comes from director John Ford’s classic film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, where a small town newspaper editor, pressed with new information that changes a decades-old story that launched various careers, states “when the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” For Manfred von Richthofen, whose career resides between the hagiographic coverage the German press lavished upon him and a heavily edited autobiography that still managed to hint at layers of personal torment, it’s difficult if not impossible to sort fact from legend. In roughly two-and-a-half years, Richthofen rose from obscurity to one of the most famous men in the world. By the time of his death at only 25 years of age, Richthofen was the highest scoring ace of the Great War, had collected 25 medals from four different countries, and was a best-selling author. He was also a shell of a man who started the war; far more morose and erratic and suffering from a serious head injury.

Richthofen had started the war in the cavalry – the kind of assignment befitting a member of the Prussian Junkers of which his family was a part. Richthofen’s noble lineage had granted him the title of Freiherr or “Free Lord”, often translated into English as “Baron” despite the connotations of being a Baron in the West as a hereditary title while Freiherr was more honorary. Regardless of the technicalities of his societal status, Richthofen’s cavalry experience was obsolete mere months into the war. Until the spring of 1915, Richthofen was basically a glorified messenger, nevertheless winning the Iron Cross for his willingness to make dangerous crossings his fellow messengers would often avoid. His transfer to the logistics branch, where he’d only oversee deliveries far from the front was too much for the young German. Richthofen requested a transfer to the Imperial German Army Air Service.

/the-red-baron-poses-with-young-officers-55830596-5c9310eec9e77c00010a5d0d.jpg)

Richthofen’s “Flying Circle” air corps – with the Red Baron [center] as “ringmaster”

The man who would become the most feared pilot in the world had an inauspicious start – he crashed his first solo flight. Richthofen’s superiors thought the young Free Lord was an arrogantly bad pilot. But Richthofen’s boldness and personality had caught the eye of one of Germany’s most famous aces of the early war – Oswald Boelcke. Boelcke would create the modern German air force, the Luftstreitkräfte, and is often credited as the “Father of Air Fighting Tactics.” But in early 1915, Boelcke and Richthofen were both relative unknowns struggling to find their places in a service trying to find it’s place within the larger world war. When the two reconnected in the late summer/early fall of 1916, Boelcke had become one of Germany’s first aces leading what the Allies called the “Fokker Scourge” that was decimating British and French air corps. Boelcke would become a German war hero and a bit of a role model for Richthofen (and really all German airmen). A shrewd tactician, Boelcke was also seen as a gentleman warrior, with exploits of him saving crashed Allied airmen and even saving a drowning French boy becoming great propaganda fodder for Berlin.

With such a reputation, Boelcke could form his own air corps and despite Richthofen not even having a confirmed victory to his name, Boelcke wanted his acquaintance for the new Jasta 2 squadron.

The Red Baron didn’t always fly red planes, but this is the image that most associate with Richthofen’s aircraft

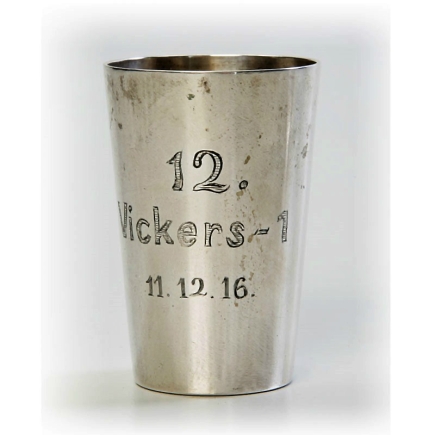

It didn’t take long for Richthofen to make a name for himself. Only weeks into his service in Jasta 2, the Prussian Free Lord scored his first confirmed kill of a British pilot. In keeping with the image of nobility that pilots wanted to project, Richthofen later remarked that he had “honored the fallen enemy by placing a stone on his beautiful grave.” Perhaps more crassly, Richthofen ordered a silver drinking cup with the date of his victory and the plane model of his defeated opponent engraved upon it. It would be a habit he’d continue until silver shortages forced him to stop. By that time, Richthofen would have 60 engraved cups.

In two short months, Richthofen had established a reputation as a daring fighter pilot. His November victory against British Major Lanoe Hawker VC, one of the first British aces and known to the Germans as “the British Boelcke,” began to make him famous. Richthofen would liken his air experience to that of a hunter and would display his victories in a similar manner, with his home adorned with fabric serial numbers from wings, instruments and machine guns looted from Allied wreckage (Hawker’s machine gun hung above his quarters). He even had a chandelier made from the engine of a French plane. By the beginning of 1917, Richthofen had been credited with 16 victories and the Pour le Mérite, the highest military honor in Germany at that time.

But Richthofen’s trophies and medals helped obscure the terrible realities that German pilots could face. Only weeks into his service, Richthofen helplessly watched Oswald Boelcke crash into another German plane and tumble from the sky. Boelcke might have been able to survive, but wasn’t wearing a harness or helmet as he smashed into the earth. As one member of Jasta 2 stated, “Destiny is generally cruelly stupid in her choices.”

One of Richthofen’s silver victory cups, with the name of the aircraft, date and the how many aircraft he’d shot down

Unlike Boelcke, Richthofen publicly downplayed the role of tactics in aerial combat. “There is no art in shooting down an aeroplane,” he wrote. “The thing is done by the personality or by the fighting determination of the airman.” The quote would fly in the face of Richthofen’s actual combat skills, suggesting the words might have been ghostwritten or otherwise forced upon him. Richthofen would build upon Boelcke’s tactics, often hiding against the glare of the sun and diving down on his opponents, all while having his flanks and rear covered by fellow Germans. He was never regarded as a talented pilot, but a bold one – within reason. Richthofen was cautious to warn young airmen not to engage with multiple targets or stay fixated on one plane, as doing so made it easier for enemy planes to lock in behind you. And as his reputation grew, it could be said that Richthofen started winning battles by intimidation. Painting his Fokker the distinctive red it would be eventually famous for would have been suicide for most other pilots, as it would be the equivalent of painting a gigantic target on the aircraft. But as Richthofen became known as the “Red Devil,” “Red Knight” and finally the “Red Baron” to his enemies, opposing pilots had little interested in engaging the winningest ace of the war. Richthofen’s fellow pilots began painting their planes red too, as much to protect their leader as to hopefully frighten off enemy aircraft.

Richthofen was quickly becoming the most famous pilot on either side in the war. Fellow Central Powers nations threw honorary medals at him; stacks of mail arrived daily at his quarters; Hindenburg and even the Kaiser would request to dine with him. But the man at the center of this attention was hardly all that interested in fame. Often described as distant and humorless, Richthofen was hardly as engaging as his “Red Baron” persona. When told by the German General Staff that they wanted him to write his memoirs, Richthofen only asked that the money from sales go to his family and treated the endeavor as an assignment, less than a grand promotional and financial opportunity.

Richthofen’s autobiography was a rushed book designed to boost the war effort. He would attempt to disown it later

Despite the fame, in many ways the war had become far less glamorous for Richthofen. Whereas he liked himself to a hunter in his early fights, by the spring of 1917 the “Red Baron” was gunning down multiple British planes a day; recording 22 kills in April alone. Now Richthofen confessed to feeling more like a butcher. In a passage of his book edited out of earlier versions, Richthofen stated “I am in wretched spirits after every aerial combat. I believe that [the war] is not as the people at home imagine it, with a hurrah and a roar; it is very serious, very grim.” This version of the “Red Baron” would never be seen until after the war as Richthofen’s book, “The Red Fighter Pilot”, would be every bit the popular, patriotic, war-cheering novel Berlin wanted. Richthofen himself would privately disown the work, saying it didn’t reflect how he now felt about the war or his role in it.

Richthofen’s seeming change of heart may have been less due to the horrors of war than directly from an injury. In July of 1917, the “Red Baron” barely escaped his own death as a bullet hit his head, leaving a 4-inch scar on his scalp that never fully closed. Richthofen blacked out from the force of the hit and lost his vision, only managing to land due to partially recovering his sight right before crashing. While he took back to the skies only weeks later, his fellow airmen and even family members noticed the difference. Richthofen now suffered from headaches and air sickness whenever he flew. And back on the ground, the once reserved “Red Baron” was now seemingly manic depressive – going from speaking with no one to now banging his head on tables to show everyone the giant, unhealed wound. His mother noted the change even before witnessing the bizarre behavior. There was “something painful lay round the eyes and temples.” The son of even just months prior was gone, replaced by a more reckless, despondent man. Even now, biographers assert that Richthofen’s death started in July 1917 as the bold but calculating pilot that had risen to fame was gone. Despite a long recovery period and numerous orders to stay out of the sky, the “Red Baron” was seemingly determined to tempt fate until his luck would run out.

The wreckage of the Red Baron’s last flight

The battle with Richthofen in the sky had ended, but the battle of credit for his defeat would be fought for years.

Captain Brown would be officially credited for the kill, but the examination of Richthofen’s body proved that Brown couldn’t have fired the killing shot, as the angle of entry of the bullet didn’t match his trajectory from where he fired. More likely, the fatal wound came from anti-aircraft fire which prompted any number of Australian and British soldiers to try and prove their shot fell the famous “Red Baron.” As much as any enemy fire, it could be argued that the German High Command killed Richthofen, as the pilot was clearly suffered from his head injury and combat stress. Similar combat stress-related pilot deaths could be seen across the Great War as talented, veteran pilots would make simple, rookie fighter errors that often led to their demise. Given that Richthofen was killed during the German Spring Offensive, where air crews were pushed to spend as much time in the air as possible, it’s likely the “Red Baron” was exhausted, both mentally and physically, when he went into his last dogfight.

The Germans had been constantly worried about the propaganda harm if Richthofen died in combat. With his body behind the British lines, they couldn’t even bury him. But despite having killed so many of their comrades in action, the British gave Richthofen a proper burial with full military honors, including even a gun salute. Allied aircrews from across the Western Front paid their respect, with one delivered wreath made out to “To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.” As one British combat reporter wrote, “Anybody would have been proud to have killed Richthofen in action…but every member of the Royal Flying Corps would also have been proud to shake his hand had he fallen into captivity alive.”

The very best memoir of a WWI aviator that I have read is “Warbirds: Diary of an Unknown Aviator.” It is more Hemingway than Hemingway, and was published before Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. There are some interesting mysteries around who the protagonist really was, but most of them have since been resolved.

I say it is the best because it has, like Hemingway’s WWI novels, a highly literary quality. It is not just a recitation of facts and dates ( a lot of WWI memoirs do this). It puts you in the daily life of an American officer of a hundred years ago. He explains, for example, the difference between an English “actress” and an English prostitute (mostly a matter of form).

The book is in the public domain.

Pingback: In The Mailbox: 06.11.21 : The Other McCain

Treating a dead opponent’s body with respect is a way of keeping your sanity in the hell of war. It helps maintain order and cohesion.