With a world at war, and new nations joining the fight, the events of May 25th, 1915 would have seemed blessedly contradictory – two nations signing a peace treaty.

There was little drama or media fanfare as representatives from Japan arrived in Peking to meet with the Republic of China’s first (semi-democratically) elected President, Yuan Shika. The course of nearly five-months of bitter negotiations, and the threat of expanded war in Asia, had led to this meeting. At issue were Japan’s “Twenty-One Demands” – a list of diplomatic concessions Japan wanted from China, including territories, industry, and most concerning for Japan’s fellow Western allies, de facto control of Chinese government ministers.

If accepted, China would become little more than a Japanese protectorate. If refused, the Great War would expand even further.

—

Japanese artillery at Tsingtao. A German-held Chinese port, Tsingtao was captured in 1914 by a joint British-Japanese invasion, setting the stage for further Japanese expansion in China

When we started this retrospective on World War I, we mentioned that it made sense after covering World War II since the conflicts “really were two different phases of the same war.” And most assuredly, the seeds of Japan’s imperialist designs on China – and war against the United States and Britain – were firmly planted on May 25th, 1915.

Japan had already played its role in the Great War; using its pre-standing alliance with Britain as the pretext to seizing German territories. Among the first battles of the Great War occurred in the East, as the German-Chinese city of Tsingtao fell to Japan after a two-month long siege. But in addition to occupying German Pacific territories that would become indelible locations during World War II, like the Mariana, Caroline, and Marshall Islands, Japan saw a greater opportunity – a chance to push out foreign intervention in China and replace it with Japanese influence.

—

Okuma Shigenobu – Japan’s 5th ever Prime Minister and the major force in drafting the “Twenty-One Demands” sent to China

The China of 1915 was beset by many of the same dilemmas as the Persians or Ottomans – economic and military weakness, rebellious provinces and/or ethnic minorities, and massive diplomatic (and sometimes military) pressure by foreign powers.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty just years earlier had created a political vacuum in which various provinces rebelled and split away from China. Tired of foreign powers holding Chinese territory and often dictating Chinese policy, revolutionaries overthrew the Qing regime and replaced it with a national assembly. Politically isolated – the movement was made up mostly of Chinese warlords and others of whose centers of influence were in the northern provinces – the assembly elected former General Yuan Shikai as the nation’s provisional President in 1913.

And like the Young Turks or the Persian Constitutional revolutionaries, Yuan found himself a leader with few followers. Despite Yuan’s reputation as a fearless military leader (he was one of the few military figures who emerged with his reputation intact after the First Sino-Japanese War of the late 1800s which claimed Korea for Japan), he gained little loyalty among the southern provinces or the newly created assembly. In turn, he went to war with both, crushing political opposition and rival warlords with force and likely playing a role in the assassination of a senior opposition party leader.

By 1915, Yuan had effectively become a dictator – abolishing the assembly en route to attempting to restart the monarchy, with himself as emperor.

—

Yuan Shikai – the first President of the Republic of China. Yuan’s acceptance of the 21 demands weakened his government and helped push him towards restarting the monarchy. He would pronounce himself Emperor before the end of 1915

With Japanese power in China at its apex and China’s political and military power at its nadir, the moment had arrived for Tokyo to press its advantage.

On January 18th, 1915, Japanese Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu and Foreign Minister Katō Takaaki presented Yuan Shikai with a simple document. It was a list of 21 demands by Tokyo – ranging from Chinese acceptance of the Japanese occupation of formerly German-held territories, to the seizure of Chinese industries in debt to Japan. Few of Tokyo’s demands were inherently a transfer of additional power. Japan already held Germany’s territories; Japan could already take legal measures against Chinese industries that owed them unpaid loans. In many cases, at worst the “Twenty-One Demands” simply codified the current state of Japan’s influence in China.

The Demands had been listed into groups, and it was in Groups 4 and 5 that Japan made it clear they were looking to do more than codify the status quo. If China accepted the Demands, they would be barred from making any further territorial concessions to a foreign power – unless that power was Japan. Japanese advisers would take over key ministries, especially in the areas of finance and policing. The Chinese military would be armed and trained and led by Japanese advisers. China would be Japan’s puppet state.

The Demands made it clear – If Yuan and the Chinese refused to sign, they would be enacted by force. China could choose only how to be conquered – by the pen or by the sword.

—

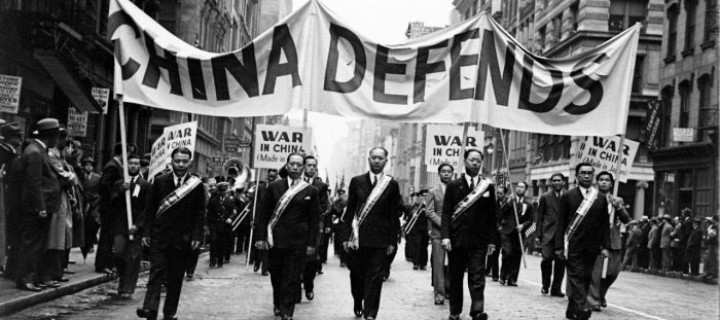

The photo is from a WWII era parade, but China’s “National Humiliation Day”, born of the signing of the Twenty-One Demands, continues to be marked into the 21st Century

The international reaction to the Twenty-One Demands was one of shock. Such blatant aggression was what the Entente were fighting against…or at least claimed to be.

Most of Europe had come to an informal understanding on China, adopting the United States’ position that an “open door policy” should define trade and other international treaties with the Chinese. No one nation should dominate Peking. But the rest of the Entente also couldn’t risk alienating Japan and possibly create a hostile military force to the West in the Far East. Thus, with one eye on their own Eastern colonial possessions, Britain and France did little publicly to rebuke Japan.

The United States took a different tact. One of the first foreign governments to recognize the Republic of China in 1911, the U.S. had increasingly viewed Japan’s actions on the Chinese mainland as belligerent. Even the pacifistic Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who would soon resign over Woodrow Wilson’s rebukes of Germany over the deaths of American civilians at sea, was willing to strike a more resolute tone over the Twenty-One Demands. Bryan insisted to Tokyo that America would not allow for “infringements” to Chinese sovereignty. The U.S., so resistant to sending troops to Europe, had sent troops to China before, in putting down the Boxer Rebellion just 15 years earlier. The implication was clear – U.S. military intervention in China was at least on the table.

Faced with a scenario in which the United States might enter the Great War against a nominal Entente ally, (however long those odds might have been) Britain began to put pressure on Japan to modify their demands. It didn’t help that Yuan had leaked Tokyo’s demands in the first place, and details from the following months of negotiations. While the initial demands had been drafted and approved by the Diet and Genrō (a sort of Japanese House of Lords), the concessions and threats made during the negotiations had occurred entirely without their input. Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu was becoming increasingly diplomatically isolated – at home and abroad.

Unwilling to risk a conflict with either the United States or Britain (or both), Shigenobu sent Yuan a revised list of demands – a “Thirteen Demands”; dropping the infamous 4th and 5th groupings that would have given Japan de facto control over China. Yuan and his advisers quickly accepted the document on May 9th, 1915. The crisis was over.

—

Young Boy, Don’t Put On Airs – it’s technically German propaganda from WW1, but it captures Japan’s attitude against the United States following the conclusion of the Twenty One Demands

The threat of another front in the Great War had ended, but the ramifications of the Twenty-One Demands reverberated for decades.

Yuan’s acceptance may have been a better option then a war China could ill-afford to fight, but the burgeoning dictator’s lingering credibility was lost as soon as his pen touched the treaty. Despite calling the limited version of the demands a “terrible shame” and declaring May 9th, the date Peking accepted the demands, a “National Day of Humiliation”, the move only cemented Yuan’s (and the Republic’s) weakness in the mind of the Chinese populace. Desperate to enhance his floundering reputation, Yuan would declare himself Emperor by the end of the year.

Shigenobu didn’t fare much better. The revised demands didn’t give Japan anything they hadn’t already captured by force of arms, and the treaty had significantly weakened Japan’s ties to their British ally. For the first time in the nearly 20 years of expansionist policy, Japan had been defeated – albeit by diplomacy, not force. Shigenobu’s cabinet would resign by the fall of 1915, in part to the debacle of the demands, and Shigenobu himself would be forced to step down soon afterwards.

Japan had learned valuable lessons from the episode. They were likely surrounded on all fronts by Western powers that were hostile to the nation’s rise. And where Japanese arms had succeeded on all battlefields in short, crisp campaigns against the Chinese, Russians and Germans since the late 1800s, Japan had lost at the negotiating table against (in their minds) Britain and America.

The next time Japan looked to expand her empire, it would be by force.

Pingback: Broken China | Shot in the Dark