It was a wet, cold, slushy March evening in Jamestown, ND. I was in the basement of the FIrst Presbyterian Church, at a church youth group meeting.

Notable fact about the group: one of the group’s leaders, a student at Jamestown College, would eventually have a son named Jared, who’d become an all-star defensive tackle for the Vikings. The guy who eventually became Jared Allen’s father was no slouch of an athlete himself; he was one of the very few people from that NAIA Division III school ever to get a walk-on tryout with an NFL team – I think it was the Rams, and I think he got as close to making the cut as anyone from an NAIA III school ever did.

But the story’s not about him or his future son.

The kids in the group were what passed for my “best friends” at that socially awkward time of my life, probably, sort of. Which isn’t to say that cliques didn’t find their way into the group. Immune to cliqueishness as I’d always been, some teenage angst was inevitable.

And for whatever reason, I had a nemesis at the youth group. Her name was Cindy. She didn’t like me, and the feeling was mutual.

And I watched, teeth clenched, as Cindy uncased a guitar and started strumming out a song of some kind or another.

I will play guitar. And I will play it better than Cindy, I resolved to myself.

I went home that night, and dug through the closet in the room I shared with my little brother. There, I muttered. The guitar.

It was a guitar that someone had left in my dad’s classroom back in the mid-sixties. It’d sat in Dad’s locker, forgotten, for several years, before he brought it home – this on the day of the first moon landing, as I (possibly falsely) remember.

And after a little dilatory plinking, it spent the next eight years doing what most guitars do in the hands of little boys; it served as a machine gun, a fort for toy soldiers, an aircraft carrier for toy planes – pretty much everything but a guitar.

But those days had passed. I needed a guitar, and a guitar it would again be.

It’d take all my stingy, cheapskate resourcefulness to make that happen. The guitar had been a very cheap guitar even when brand new – a “May-Bell”, the kind of thing you got in the Sears catalog for $19,99 back in the sixties; it was apparently part of a long line of cheap instruments.

Its years of abuse had left it the worse for wear; there was a crack in the back and another in the front; it had two remaining strings, and it was missing three tuning heads.

I wasn’t completely green at this; I had played cello since fourth grade, and had picked up a few tricks, and had a few contacts. I gathered my paper route savings and went to work.

And so on Monday, March 14, 1977, I walked into Midwest Music – a tiny little hole in the wall on main street in Jamestown. I bought a pack of strings, dug through an odds and ends box for some parts to assemble some one-of-a-kind tuning machines, and a little tube of wood glue to try to repair the cracks.

I also bought a copy of the Gene Leis “Nexus Method” guitar book – basically a chapter on how to hold the instrument, a chapter on how to read chord frames, and then 20 pages of photos of chords.

It was a fortuitous choice; the book’s tag lines said “If you don’t know your chords you’ll never play enough guitar to be dangerous”, and I took it to heart. It was a brilliant maxim, and it served me well. And I had one huge benefit – four years on the cello had taught me out to keep time, what intervals and chords were, and how music fit together.

The maxim was good. Unfortunately, for all my cheapskate ingenuity, the MayBell was another story. While I did a serviceable job repairing it, it was pretty much a disaster of a guitar. It wouldn’t stay in tune (the wood glue didn’t really fix the cracks, and more importantly didn’t give the structure enough rigidity to stay in tune at all).

It was there that serendipity stepped in.

My dad had spent the previous year on sabbatical from his job at the high school, teaching in the education department at the college up on the hill. One of his students was a young woman who was a music and education major from rural northern Californnia, who had just dragged her fiance – who, in a fun example of the circularity that seems to plague my autobiographical stories in this blog, was the future father of Jared Allen (whom you met in the second paragraph above). They had broken up; Mr. Allen had a new girlfriend and a new best friend from the football team (a guy from Crystal, MN named Mick Burns, who is now a Presbyterian minister in Virginia) who asked him to come down and help with the youth group at the church…

…but I’m digressing. Jared Allen’s future father’s ex-fiance, Jenny, who’d become a bit of a friend of the family, noticed how gamely I was wrestling with the jury-rigged MayBell, and noted that she had a Yamaha classical guitar that she’d tried learning to play once upon a time, and didn’t have time for, and that I could borrow until she graduated from college.

And so I set to work with a vengeance and, armed with the knowledge of what a guitar sounded like when it could actually stay in tune, and 20 pages of chords to learn, I started learning music.

And ran quickly up on a reef of ignorance; I just didn’t know that much music, other than the classical stuff I played on my cello at school. My parents, God bless ’em, weren’t musicians, much – and when the radio was on around the house, it was usually tuned into CBW in Winnipeg, because it was the closest thing to NPR you could get in rural North Dakota at the time.

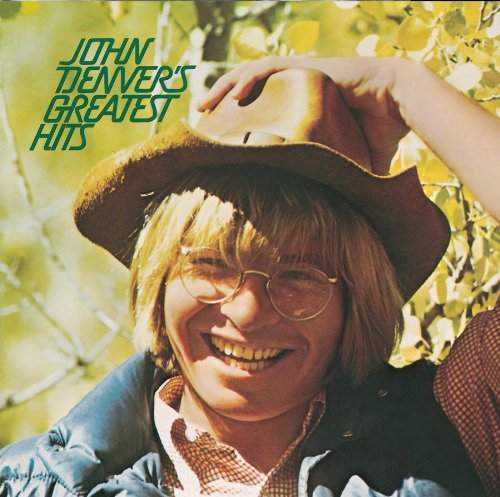

I had heard a few songs by one artist, though – John Denver. And so I grabbed a copy of the sheet music for his Greatest Hits album.

And for probably six months, I sat in my room most every night and woodshedded on that album. “Follow Me” and “Leaving on a Jet Plane” were the first songs I ever managed to play coherently – and from there, my musical world kept expanding; “Back Home Again” was where I had my “ah hah!” moment on how fourths and fifths play together, and how to do a rolling sixth (which you use in every Chuck Berry song, and thus most everything the Rolling Stones and Mike Campbell ever played). “Take Me Home, Country Roads” taught me how relative minors work – and you can’t play anything on Born to Run without relative minors! I got to “Sunshine On My Shoulders” – and discovered the perfect song for learning the basics of fingerpicking. The whole thing is a languid eighth-note pattern – like drumming your fingers on the table, once you learn your chords. And “Rocky Mountain High” is a great little workout on how chords fit together.

And so by the middle of that summer, I could play…a bunch of John Denver songs. It seemed like it took forever – and occasionally felt like it. My fingers did, occasionally, literally bleed. In retrospect, it was blazingly fast; anger was a great motivator!

But even then, I knew – knowing how to play John Denver wasn’t going to land me any babes. And so I started branching out.

I found a copy of the sheet music for “Sundown”, by Gordon Lightfoot, and learned how to play moving chords fluidly in a progression.

And right after that – in July of ’77 – while sitting and listening to the radio in my room, I heard Styx’s gloppy, pompous faux-art-rock classic “Come Sail Away”. It was inescapable back then, let’s be honest.

And as I played along with the big, climactic guitar part, I strummed a “C” – and then an “F”, and a “G”, and then back to the “F” – and it all clicked; that’s how the song went together. I learned it by follow a standard chord progression (1 to 4 to 5 – the progression you use for everything from “Louie Louie” to “Wild Thing” to “Twist and Shout” to “Born to Run”), and back, without needing to buy sheet music for it

And it was like the floodgates opened. By that fall, I would sit in the chair in the corner of the room I still shared with my brother, doing homework, with my guitar at my feet, and listen for any songs to cross the radio that I wanted to learn; I’d pick apart the chord progression, faster and faster, and pretty soon be playing along pretty fluently; by early winter, I knew most of the KFYR “Torrid Twenty” every week. I learned hundreds of songs – some that I still remember;

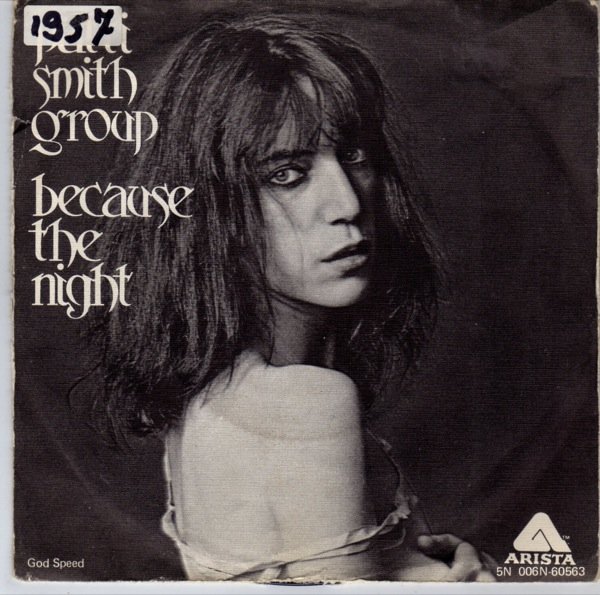

“Hot Child in the City” by Nick Gilder, “Fooling Yourself” by Styx, “Logical Song” and “Give A Little BIt” by Supertramp, “Help Is On Its Way” by the LIttle River Band, “Three TImes a Lady” by the Commodores, “Miss You” by the Rolling Stones, “Baker Street” by Gerry Rafferty, “Two Out Of Three Ain’t Bad” by Meatloaf, “Dancing Queen” by Abba, “Dust in the Wind” by Kansas (fingerpicking and all), “Magnet and Steel” by Walter Egan, “Still the One” by Orleans, “Night Moves” and “Hollywood Nights” and “Mainstreet” and “Still The Same” by Bob Seger, “Don’t It Make Your Brown Eyes Blue” by Crystal Gayle, “Because the Night” by…Patti Smith (it’d be months before I learned who Bruce Springsteen was), “Running on Empty” by Jackson Browne, “Wild Fire” by Michael Murphy, “Werewolves of London” by Warren Zevon – and learned them so indelibly I can play all of them, note for note and word for word, today – even the one hit wonders (Nick Gilder? Really? Yes. Yes, I can).

And sometime in the next year, it led me to my next big project; learning how to be a lead guitar player. And after hours of trying to decipher how it was done, I had my first victory; the solo from “More than a Feeling”, by Boston.

And once that fell into place, the whole musical world opened up to me; by tenth grade, I was not just a greasy-haired dweeb. I was a guitar player. I had an identity, and it was damn fine.

And it started forty years ago this past Tuesday.

One thing that ended not long after that anniversary was my junior-high enmity with Cindy. We actually became friends through high school and then college. And around college graduation, I mentioned to her that she was the reason I started playing guitar in the first place.

“Huh”, she responded “I think I quit the guitar right after that”.

Anyway – I got hooked. About a year after I rebuilt the Maybell – just before Jenny graduated and needed her guitar back – I bought my first guitar, a Ventura acoustic that I still have (although it needs some TLC). Then, the summer after 9th grade, my first electric, a 1961 Fender Jazzmaster. I still play that one; God wiling, I’ll hand it down to my son, also a guitar player, someday.

And eight years later, it led me elsewhere.

More later today.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.