Since the end of World War II, the mantra of government and business is that “we need more kids to grow up to study Science, Technology, Engineering and Math” – aka “STEM”.

And yet if you work in technology, you know that in vast swathes of the field, there’s no real shortage of people. Especially in IT; even as baby boomers retire, there is plenty of unemployment among IT people; even as demand for IT workers booms, the supply seems to more than keep pace. Have you checked out the contract rate for web coders or support analysts lately?

And yet the government keeps cajoling our “best and brightest” to go into STEM.

Why?

To keep the costs down, perhaps?

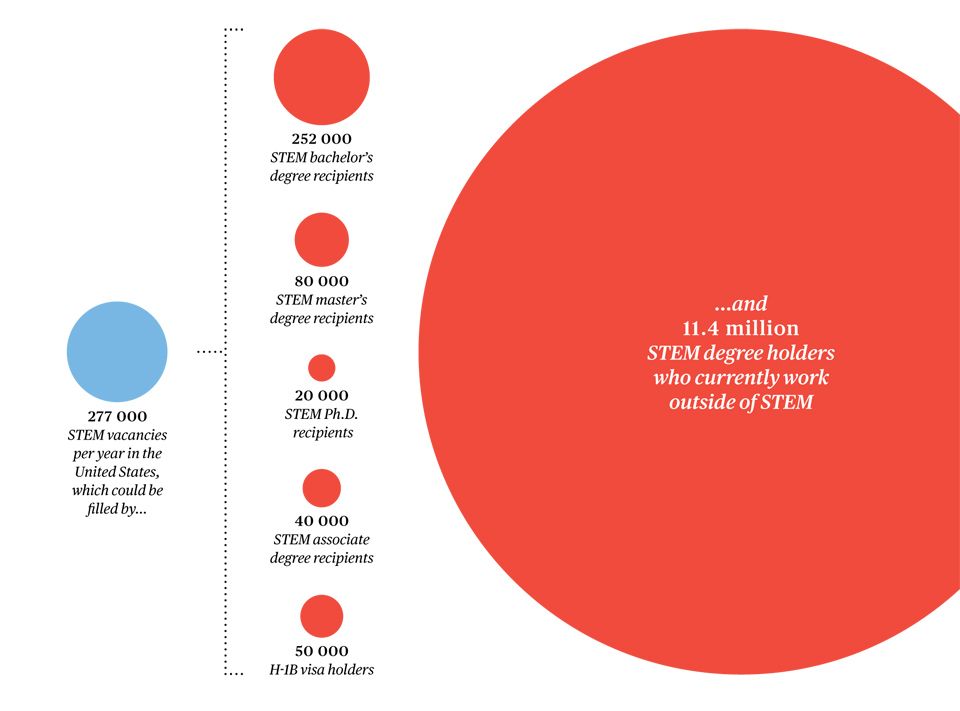

As this piece in the IEEE Spectrum notes, not only is there no shortage of STEM professionals, there’s an apparent skills mismatch, with many “STEM” careers being held by non-STEM degree-holders (I’d be one of them, by the way), and many STEM degree-holders working outside science and technology.

And yet the establishment keeps driving more people into STEM, and importing more programmers, engineers and technicians from overseas.

Why?

Clearly, powerful forces must be at work to perpetuate the cycle. One is obvious: the bottom line. Companies would rather not pay STEM professionals high salaries with lavish benefits, offer them training on the job, or guarantee them decades of stable employment. So having an oversupply of workers, whether domestically educated or imported, is to their benefit. It gives employers a larger pool from which they can pick the “best and the brightest,” and it helps keep wages in check. No less an authority than Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, said as much when in 2007 he advocated boosting the number of skilled immigrants entering the United States so as to “suppress” the wages of their U.S. counterparts, which he considered too high.

And it helps inflate the higher-ed bubble, too:

And the perception of a STEM crisis benefits higher education, says Ron Hira, because as “taxpayers subsidize more STEM education, that works in the interest of the universities” by allowing them to expand their enrollments.

An oversupply of STEM workers may also have a beneficial effect on the economy, says Georgetown’s Nicole Smith, one of the coauthors of the 2011 STEM study. If STEM graduates can’t find traditional STEM jobs, she says, “they will end up in other sectors of the economy and be productive.”

The problem with proclaiming a STEM shortage when one doesn’t exist is that such claims can actually create a shortage down the road, Teitelbaum says. When previous STEM cycles hit their “bust” phase, up-and-coming students took note and steered clear of those fields, as happened in computer science after the dot-com bubble burst in 2001.

Emphasizing STEM at the expense of other disciplines carries other risks. Without a good grounding in the arts, literature, and history, STEM students narrow their worldview—and their career options. In a 2011 op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, Norman Augustine, former chairman and CEO of Lockheed Martin, argued that point. “In my position as CEO of a firm employing over 80 000 engineers, I can testify that most were excellent engineers,” he wrote. “But the factor that most distinguished those who advanced in the organization was the ability to think broadly and read and write clearly.”

For all the sneering people are doing at humanities these days – and I have a BA in English with minors in History and German – the selling of the STEM “crisis” seems to be a move to commoditize technical skill. Communications is no commodity, though – and it seems to be what still what separates a bench engineer and their supervisors.

So is the education system short-changing students by preaching STEM as the be-all and end-all of opportunities?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.