It was a chilly, rainy night in March of 1983.

I had a horrible cold – but no matter. I was standing on a riser in a tumbledown little church in Pendelton, Oregon, with 69 or so other college kids. And by this time in the tour, cooped up on buses for day after day, most of us were sharing colds.

I had just finished a brisk walk up to the stage for the second of three sets of the evening’s performance. It was our seventh or eighth concert in as many days and nights.

The house lights dimmed, and the stage lights came up, blotting the audience from view. We focused on the conductor’s podium, where presently a guy in a formal tuxedo climbed onstage. His cheeks were puffy and red, but his eyes were clear and sharp- “fierce”, I’d say, if the fashion industry hadn’t so devalued the word. He smiled -partly greeting, partly saying “can you keep up with me?”

He lifted his hands, and brought them down. And we sang – launching a capella and without fanfare directly into “Have Ye Not Known/Ye Shall Have A Song”, two movements from Randall Thompson’s oratorio “The Peaceable Kingdom”, a piece lifted from Isaiah 40:21:

Have ye not known?

Have ye not heard?

Hath it not been told you from the beginning?

Hath it not been told from the foundations of the earth?

(Here’s a high school choir doing it).

I sang my part, nestled into the midst of seventy college kids who, for a couple of hours, felt like a single organism that was much better than the sum of our parts, as the conductor – listed on the program as Dr. Richard Harrison Smith, and never anything else – wrung the last little bit of execution, passion and yes, joy out of the evening.

And while I didn’t dare make any facial expression, or even take my eyes off the podium, I smiled inside.

———-

I remember “Dick” Smith, as my dad always called him, probably about the same time he moved to Jamestown, ND. He and his family – his daughters, Kristin and twins Karen and Kathryn, all about my age – came by our old house in Jamestown, along with his wife, June, who’d just been hired as Dad’s colleague in the Jamestown High School English department. Smith had just taken over the music department at Jamestown College, after earning a PhD in music and an MA in Biochemistry. I wonder sometimes if academia today would know what to make of a guy like him.

But I was years away from knowing any of this. I was six years old.

Now, if there’s one thing people in small college towns appreciate – or appreciated, in those days before the internet and ubiquitous TV and travel – it’s whatever scraps of culture they can get. And Dr. Smith quickly started producing some amazing culture.

In town, we noticed this mostly from the college’s annual Christmas concerts – which morphed from sleepy little affairs into six-night runs with choir, concert band and elaborate production, lighting and sets, that drew packed houses and TV coverage. Packing into the college’s Voorhees Chapel, to the smell of pine boughs and scorched gels, is one of the most potent memories of Christmas as a child.

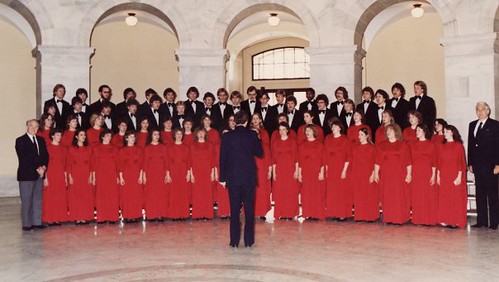

Unbeknownst to me – because I was years away from caring about such things – Dr. Smith, starting in 1969, built the JC Concert Choir into one of the premiere college choirs in the United States. One review from the seventies – and no, I couldn’t find it if I tried – placed JC’s choir among the top three small-college choirs in the US – in the same league as the legendary St. Olaf Choir, in the (choir geeks will know this) Christenson era. In 1972, the Jamestown College choir became the first American choir to sing at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. In 1978, he engineered a visit to Jamestown by the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra to accompany the choir in a concert – the highlight being Bach’s Magnificat, if I recall correctly.

You might be thinking “this is a small college choir that fought above its weight”. It was – but that wasn’t even the amazing part.

The amazing thing about Smith’s choirs throughout their history? While the other top-flight choirs, like St. Olaf’s, were made up of music majors and especially voice students, Jamestown just wasn’t that big. In the seventies, the place had 600-700 students, maybe a couple of dozen of them music majors. Over ten percent of the entire campus sang in the choir – less than a quarter of them music majors. Imagine a tournament-grade basketball team that was 3/4 walk-ons from the Theatre and English and Nursing departments; it was the same basic idea.

And so year after year, for almost thirty years, Dr. Smith created top-flight college choirs from virtually nothing.

———-

When I graduated from high school. I didn’t know what I wanted to be – but I knew I wasn’t going to major in music. Still, I’d had some musical training – none of it involving singing. I played guitar, cello and harmonica, and sang in a garage band, in a voice that was best suited for shouting out Rolling Stones and Clash covers. That was all the singing I ever wanted to do. I was an instrumental guy, and proud of it.

I’d known Dr. Smith and his family for about 12 years by that point – his wife June was my high school creative writing teacher; Karen and Kathryn were classmates at Jamestown High School (Kristin graduated a year before me).

My mom worked as a secretary in the nursing department at Jamestown College, which would net me a nice tuition break, so in the spring of 1981 I enrolled at “JC”. Of course, every penny counted, so I seized on every scholarship I could find. I got a grant to work as a stagehand in the theatre department and, late in the game, was recuited to play cello in a chamber group, and percussion and guitar for the concert and stage bands.

One day, my senior year of high school, I went up to the campus to close the deal on the music grants. I walked into Voorhees Chapel for a chat with Linda Banister – and my spidey-sense started buzzing away; something seemed just a little bit off.

There were always plenty of women auditioning. then and always, for 35 or so soprano and alto slots – but in a school like JC, finding guys who could fill the choir’s 35-odd tenor, baritone and bass seats was a constant battle. Smith, and his assistant, Linda Banister (a voice teacher who did double duty as the choir’s manager) prowled the campus, looking for guys who sounded like they that could be jury-rigged into instruments in a choral ensemble; they filtered through high school transcripts looking for hidden semesters in “choir”; they staked out football practice, listened in the cafeteria, and even (rumor had it) prowled the dorms, listening for guys singing in the shower. The men’s sections – the tenors, baritones and basses – were a grab bag of football players, computer-department night owls, and just-plain guys who could, to their amazement, carry a tune, most of them with absolutely no musical training whatsoever, most of them enticed by having $1,000 a year lopped off their $4,000+ tuition; such was the choir’s clout.

Anyway – after a too-short discussion that ended up with grant in hand way too quickly, Mrs. Bannister said “Now you need to go down to Dr. Smith’s office”.

“Er – to talk about the instrumental stuff?” I asked, warily.

“Yeah, sure!” she said, fast enough to make me even more suspicious.

I walked downstairs into Dr Smith’s office, in the basement of the chapel. He was already sitting behind the piano.

“Hi, Mitch”, he said – first names were fine, he’d known me forever. Then, before I could respond, “OK, say “Mi Mi Mi” and sing along with this pattern”. He pounded out a “C” arpeggio.

Nonplussed, I sang. “Mi Mi Mi Mi Mi Miiii”, up and down the “C” chord..

He walked me through several more patterns, up and down the keyboard, figuring out my range. “You have a good ear; we can work on the technique. You’re a baritone!”

And that was pretty much it. I’d been shanghaied. Linda Banister was waiting outside the office. “We really need you in the choir…” she said. Being a small-town Scandinavian, my need to please others would have kicked in even had she not told me that singing in the choir was worth a $500/semester off tuition.

And so I joined the choir. I’d be in the baritone section come the fall.

———-

Or would eventually, anyway. Because before we could start choir that fall, Dr. Smith – and all of us, really – had a wrenching, existential diversion.

On top of being a great musician, arranger and director, Dr. Smith was also a footnote in medical history. A very important one, actually.

In the summer of 1981 – the hot, arid three months before I started college – word made the rounds in Jametown that Dr. Smith had gotten very, very sick at the family’s lake cabin in northern Minnesota. A very rare congenital enzyme deficiency had caused his body to start to destroy its own liver. He was in a coma and near death at a hospital in Fargo.

And at the metaphorical and literal last moment, the decision was made to fly him to the University of Pittsburgh for a medical procedure that teetered on the brink of science fiction at the time; a liver transplant.

At the time, liver transplants were almost as rare and difficult as heart transplants; the liver may be, after the brain, the body’s most complex organ. The biochemical system that the liver manages is as convoluted as anything in nature. And it showed, medically speaking; at the time, nobody had lived even a year with a transplanted liver. The body inevitably rejected the tranplant, as if it was a bacterium or a splinter. The way it was designed to do.

Liver transplants were so experimental, insurance companies were still years away from covering them. The key to success – and it was an immutably elusive key, up until the spring of 1981 – was to quell the body’s immune system’s natural response of sequestering it off and killing it.

Shortly before Dr. Smith flew to Pittsburgh that summer, a new drug – Ciclosporin – was introduced. Refined from a fungus found in the soil somewhere in Norway, it’d been used in treating a variety of other diseases – but it was going to be tried for the first time to prevent organ transplant rejection.

And Dr. Smith was Patient 1.

It wasn’t just the drugs. Some of the very equipment and techniques that make the miracle of liver transplantation seem so commonplace today were invented as a result of Dr. Smith’s surgery. From a Pitt Medical School publication on the transplant:

Fortunately, a donor liver became available. As Dr. Starzl (the surgeon who pioneered the technique of the live transplant at Pittsburgh) pointed out in his book, the surgical team fought throughout the night to control the bleeding during Richard’s surgery.

Anesthesiologist Dr. John Sassano administered two hundred units of blood, pumping each unit by hand. When Richard survived the operation and Dr. Sassano’s job was done, Dr. Starzl reported that Dr. Sassano broke down and cried out of relief and exhaustion. Dr. Sassano went on to invent the Sassano pump, a rapid blood infusion system still in use today.

The surgery lasted 14 hours.

That I’m writing this article today should tell you it worked – all the pieces; the surgical skill, the brand-new, untried techniques and drugs, and of course the liver, from a 19 year old auto-crash victim.

———-

It was a solid semester before he came back to the choir. The cocktail of drugs he’d been given, including the Ciclosporin, had played hob with his system. He’d gained a lot of weight; his formerly hawk-like face was swollen. And he could only direct for short periods, sitting on a stool, before he’d get tired and hand the choir over to his backup director.

But once he started, you could tell he lived for it.

And during the second semester of my freshman year, Dr. Smith gradually worked his way back onto the podium; by the time of our spring tour, he managed to direct (as I recall) every concert at every stop on the way.

I’ll let that sink in; in eight months, he went from comatose to doing his job (albeit not at 100% just yet), with a stop along the way for a gruelling, body-crushing, experimental, never-before-seen bit of beyond-major surgery.

We knew it was remarkable back then; having nobody to compare it with – every previous liver transplantee had died in that kind of time – none of us knew how remarkable it was.

———-

If my experience with high school music groups – orchestra, stage band and the like – was like Pop Warner football, choir with Dr. Smith was like suddenly walking into Vince Lombardi’s training camp.

Smith was a renowned arranger and conductor; his specialty, oddly, was traditional Afro-American spirituals; a Canadian paper once praised the Choir for being the most authentic-sounding choir of rural white kids they’d ever heard.

Beyond that? The programming every year was very non-trivial. It spun between spirituals, modern/avant garde choral work, and the classics of the repertoire – and by classics, I mean the hard stuff.

The highlights? Every couple years, Smith would break out a new Bach double-choir motet. My freshman and senior years, it was Motet Number 7, Singet Dem Herrn. 15 minutes and 90-odd pages long, it required the choir to split into two separate choirs, singing Bach’s, well, baroque composition in eight part counterpoint and harmony.

All from memory. Smith allowed no sheet music on stage, and the choir was rarely accompanied (as in, one song that I recall in four years).

Go ahead and try it in the shower when you get a moment.

That took discipline. All practices were mandatory; you got two excused absences a semester, and even those were discouraged (I don’t remember taking more than one in four years). The rules on stage were simple and uncompromising; once Smith stepped on the podium, in concert or late “concert rules” rehearsals, you didn’t look away, at the risk of a ferocious tongue-lashing during the break. If you got sick on stage, you did not walk offstage; you sat down on the riser and your neighors closed ranks around you. If your nose itched? You let it itch; scratching your nose, or anywhere on your face, inevitably looked like picking your nose. You didn’t question Dr. Smith on any of this.

The choir practiced four days a week, over the noon hour, to accomodate everything from after-school football practices to afternoon chem labs. You earned that $500 tuition break every semester.

To turn that throng of misplaced football players, dorm-potatoes, waylaid cross-country runners, computer science majors and the odd musician into a solid choir, Dr. Smith smacked us with something that most of us had never encountered before, and only rarely since; an uncompromising demand for excellence.

Excellence is a word that’s gotten abused horribly in the past thirty years. A wave of business books perverted the terms into meaning “a businessperson given him/herself license to be a prick”.

The word itself never came up, that I recall, in four years with the choir. But it’s what Dr. Smith demanded of all of us. Whoever we were – wrestlers, pre-meds and vocal majors alike, we had it in us to do great music – Bach, or spirituals, or avant-garde adaptations of Shaker liturgical chants alike – the way God himself intended them to be done. Perfectly.

And he didn’t tolerate half-assed choral music, and he never cared who knew about it. Botching an entrance or scooping a high note could earn a section, or a singer, a chewing out in front of the whole choir – and the privilege of singing the part yourself, solo, over and over, as the whole choir sat and listened, until you hit it perfectly.

So we – wrestlers, pre-meds, dorm-potatoes, phy-ed majors and voice majors alike – developed a keen ear and a sense of precision that was new to many of us, even if we had some experience with formal classical music.

He had no time for contemporary music. At least once a year, he’d get frustrated by some bit of pop-music frippery, and bellow “Do you think people will be listening to the Beatles in 300 years?” I was often tempted to respond “if there’s an entire academic discipline dedicated to seeing that it does, then sure!”, but he didn’t sound like he wanted a discussion…

Even other choirs felt his wrath. A choir from another college performed an assembly before practice one day. A “contemporary” choir with microphones and a PA and accompanists and a repertoire of mediocre modern choral music, they were also – by Smiths’ standards – unforgivably sloppy in their intonation and timing; they were also slow in tearing down their elaborate stage rig as we filed onto the stage for our noon practice, and milled about in the chapel, chattering away, getting ready to go back on the road themselves. We saw Smith, fuming at both the late start and the sloppy music, and took our places quickly and silently as the other choir milled about the place. We just knew this could not end well.

When Smith finally got the podium, his face was red with rage. He uncorked one of his vein-bulging jeremiads about the worthlessness of sloppy, inferior music – he referred to “this…crap!”, as I recall, which shut the other choir’s kids up but fast. He ran down their intonation, their entrances, their reliance on a mixer to balance their – shudder – microphones, their sloppiness – and compared some of our own traits with what he’d just endured. Then he had us ready up one of our own songs, in a tone that strongly hinted we’d best blow the doors off that tune.

And we did, as I remember. We didn’t dare not stick the landing. We sang the hell out of that tune, as the other choir silently shrank from the sanctuary.

We were the JC Choir, dammit.

Of course, Smith’s temper was tempered with a sense of humor and an approachable affability. Sitting in his office, or on the choir tour bus, or during a good rehearsal, he was quick with a joke – usually awful – and a smile and a word of encouragement.

And it’s worth noting that his relentless pursuit of precision and perfection didn’t cover every aspect of his life. Navigation was a good example. While on tour, generations of choir members learned the meaning of the”Smith block”, as in Smith ordering the bus to a stop in some strange city in a place where the bus had a hard time finding our destination, and telling everyone to grab their luggage and walk the rest of the way. “It’s just a block”, he’d assure us. I remember walking a solid mile through the streets of Basel, Switzerland, enjoying a warm, humid evening on a “Smith Block”-long stroll, lugging my backpack and my concert clothes down the Totengässlein, feeling like a tourist.

Smith could laugh about that along with everyone. There’s a reason generations of students loved the guy.

———-

Jamestown College was a small, private, Presbyterian-affiliated school – a sister-school to Macalester, although without the political implications, in those days. And like a lot of small colleges, Jamestown went through some lean years. Part of it was the farm crisis; lots of small colleges failed back then. Part of it was bad management; the college had a really, really bad president for a few years there.

But the school excelled at three things; athletics (the football, basketball and track programs were at the top of the NAIA Division III standings), nursing (one of the best nursing programs in the US at the time) and the Choir.

And so part of the job was to go out and raise money for the college. For four years, our “spring break”, every year, was to go out on the road on a national concert tour. Tours involved long days on the bus, taking off often before the sun rose, arriving in a new town late in the afternoon, setting up our risers and lights (that was my gig – I was a stagehand, after all), suiting up for the gig, taking a deep breath, singing a couple of hours, and then going home with a host family from the church that was sponsoring the gig. We got a free day at the apex of the tour.

As of spring break my Freshman year, the biggest city I’d ever seen was Fargo. Tour changed all that; each stop in turn, St. Cloud and Madison and Toledo and Philadelphia and Washington DC, was the biggest city I’d ever been in.

And in the three following spring breaks – Seattle, Denver and Phoenix, and every mid-sized city and tiny town with a Presbyterian church with a music-loving minister in between, we toured, ten or twelve days at a shot.

And the biggest tour of all – our trip to Europe, in 1983. We sang in little villages – Uitgeest, Holland, and Altenburg, in Schwabia – and major cities, Basel and Mainz and Köln and, biggest and best of all, Notre Dame de Paris.

Where we stood, in a church nearly a thousand years old, built long before sound amplification systems were built, in a building designed to magnify the unamplified human voice, and sang at a mass stuffed with Bishops and Archbishops and other popery, and sang to packed houses, and thought for a brief moment that God had taught Man to build buildings like this just for choirs like ours.

And a few days later, in Köln, where we sang a duo concert with the Köln Polezeichor, the city’s police choir, themselves an excellent group. After the show, the cops hauled us all and sundry to a bar frequented by Köln’s finest; our money was no good there. And it was noted that Dr. Smith’s liver was now of legal age. And as we partied into the wee hours, Dr. Smith had a beer (with his doctor’s blessing; Dr. Smith was as diligent with the gift that had saved his life as any human could be). And as we walked – I was probably staggering more than walking – back to our hotel through the streets of Köln in the weeest hours of the morning, I looked at Dr. Smith.

And he was as happy as happy gets. This – making music, and getting flocks of kids to make it, and make it very very well, was his happy place.

———-

The last time I sang with Dr. Smith was October, 1994. The college threw a 25 year “All Choir Reunion”. About 400 people – around half of the people who’d ever sung in the choir in those 25 years – came back to Jamestown to sing a concert with Dr. Smith. It was such a huge event, we used the Jamestown Civic Center. And people from my class in the choir sat with and sang among several generations of choir “kids”; some who’d been there at the beginning in 1968, and who’d been at that first “gig” at Notre Dame in 1972; some who’d just graduated, and hadn’t yet assimilated all that Dr. Smith had taught them.

And it was a joyous night – one of a short list of highlights of my own life. I was able to tell Dr. Smith pretty much exactly that; how glad I was to make the reunion, and the impact he’d had on my life. Of course, I had to stand in a long line; I think everyone was there to say the same thing, one way or the other.

Smith retired in 1998. The travelling was harming his health.

———-

The average liver transplant holds out for ten years. Partly it’s due to the whole “new liver” thing – all the risks attendant to transplants.

Partly it’s the drugs that bombard the body to make the transplant happen at all. They take a terrible toll on the rest of the body – especially the kidneys. Dr. Smith got a kidney transplant in 1997 – from his wife June, incredibly. It bought time – and bought it for a guy who’d already run the account a lot further than anyone could reasonably expect.

Dr. Smith was the longest-lived person in the world with a liver transplant. His transplant surgeon, Thomas Starzl, “the father of the transplant”, featured Smith prominently in his book Puzzle People – his own look into medical miracles and the people who live them. Starzl chalked Smith’s survival up to many things – an iron-clad constitution, rock-solid faith, and a mission in life among other things- but at the end of the day, even that most gifted of medical scientists had little empirical idea how Smith had so clobbered the odds.

But the run ran out. Dr. Smith died late last night; the kidneys, and the liver which had served two owners so well, finally gave out. He was 73. He leaves behind June – one of my favorite high school teachers – and his daughters, Kristin (a reproductive endocrinologist on Long Island), and the twins, Kathryn and Karen, my high school classmates, a teacher and nurse respectively, both in the Fargo area. They’ll miss him of course – and so will the thousand or so of us whose lives he touched as director, and the hundreds of thousands who watched and listened to his work over the decades.

Yeah, me too.

Rest in peace, Dr. Smith. And from the bottom of my heart, my condolences to June, Kristin, Kathryn and Karen.

———-

Back on that rainy night in Pendelton in 1983, the song turned into its homestretch; from the bombastic “Have Ye Not Known!” of the fanfare, through a turbulent middle section that seemed to represent the nagging doubts of the faithful, into the ending, the best part; a three-minute canon, simply repeating one line, over and over again:

And gladness of heart…

The line never changed – starting with the sopranos, quietly hinting it; the altos came in, more broadly, then the tenors, and then the basses, in a broad, three-minute crescendo. But the song modulated through a circle of…fourths? Fifths? Mostly? Big, broad, beefy resolutions that just as suddenly modified into another set of fourths, like doubts resolving into answers and then into more doubts with even bigger, more satisfying answers.

I looked at Dr. Smith, on the podium, growing more animated as the volume swelled- because looking at the director, and nothing else in the world, what you did in the choir. But as the song swelled, the diffusion from the stage lights seemed to me to form a corona of refracted light around the Conductor; maybe it was a trick of the light, or maybe it was my eyes getting every-so-watery from the sheer sonic glory of it all. And as his arms thrashed at the air, wrenching more sound, more passion, more joy from the moment, Dr. Smith looked ecstatic; the song and the choir were like a natural phenomenon, like he was playing a pipe organ whose pump was driven by a hurricane, like he’d wrapped his arms around a tornado with a “speed” button that only he could control.

Like God Himself could hear his choir, so he’d better keep us on our A game.

And I stood in the middle of that swirl of spine-tingling modulating fourths and fifths and ricocheting parts and, for one shiver-up-the-spine moment, felt as close to transcending the here and now as I ever had, or have, in my life.

And I think Dr. Smith did, too.

It may have been a first for me.

Dr. Smith? With all the choirs of farm kids and wrestlers and business majors that he wrangled into musicians? He was a regular there.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.