By the standards of the preceding weeks, the activity at Hanford on the night of March 10th, 1945 was relatively quiet.

The Hanford Site, sitting on the banks of the Columbia River in Washington state, was the first large-scale plutonium production reactor in the world. The facility had just produced the plutonium delivered for the Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico a month earlier. While that first batch of plutonium had taken Hanford over a month to produce, the site was now quickly shipping large quantities of plutonium every five days as the first atomic bombs were being assembled. The work was top secret (few staff even knew what they were producing or why) and extremely dangerous.

Thus few could have anticipated the explosion outside the site that knocked out power to the reactor’s cooling pumps. Without electricity running the cooling pumps, the reactor could have easily melted down. Who could have known the military value of Hanford, yet alone where to strike at such a vulnerable part of the site? The answer was even harder to believe – the explosion had been the result of a billion-to-one shot; a bomb from a Japanese Fu-go or “fire balloon.”

—

From the moment Japanese bombs had fallen on Pearl Harbor, the Imperial High Command had dreamed of striking the American homeland. And while there were a handful of incidents throughout 1942 of Japanese submarines shelling the U.S. and Canadian coasts, these were, at best, singular attempts to cause panic. A concentrated campaign against the American interior had not been given serious consideration. An earlier proposal of putting the Japanese equivalent of a submarine “wolf-pack” together to strike Los Angeles on Christmas Eve in 1941 had been dismissed amid Japanese concerns about potential retaliation.

By late 1944, the Japanese position on striking the U.S. had shifted as American B-29s devastated Japanese cities and industry. Nevertheless, the practicality of hitting the U.S. remained a sizable issue. Conventional targeting was considered, but extremely difficult to engineer. Not unlike Germany’s Amerika Bomber project, the Japanese Project Z was a theorized mega-bomber intended to launch from the home islands, bomb American factories, and return. But the scale of the plane, and the resources required to complete it, were beyond Tokyo’s capabilities by this late stage in the war. If Japan was going to bomb the U.S., it would have to be on the cheap.

The fūsen bakudan (“balloon bomb”) proposal devised by Major General Sueyoshi Kusaba was neither cheap nor easy to produce. But the unconventional campaign was the only one Japan could mass produce with any shot of reaching the United States.

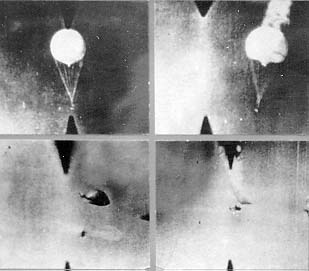

Conceptually, the operation seemed simple enough. With the recent discovery of what would be known today as the jet stream over the home islands of Japan, Kusaba and his technical consultant Major Teiji Takada proposed sending hydrogen balloons with timers and bombs attached over the Pacific to hit the U.S. While the odds of an individual balloon reaching America, yet alone a target of any value, were preposterously low, if Japan could produce enough balloon bombs, surely some would hit the U.S. and cause panic, if not at least a little destruction. Given that the bombs would only take 3 days to reach North America, Japan could be at least assured of knowing right away whether or not the campaign was working.

For an Imperial Command that was sacrificing soldiers and pilots by the tens of thousands in suicidal attacks, the idea that simple balloons could wound the American Giant was too tempting to pass up.

However, the campaign was not as easy as Kusaba expected, nor as cheap as Tokyo had hoped. Hydrogen balloons rose in warmer weather and fell in colder conditions, resulting in early test balloons either popping by ascending too quickly or descending out of the jet stream at night. A complicated control system had to be designed to cut loose ballast as the balloon rose, while an equally difficult system to time the fuse for the bomb’s release needed to be built from scratch. The systems were expensive and far from fool-proof; many balloons exploded early or went significantly off-course.

The balloon itself was another expensive invention. Traditional silk balloons leaked badly and held together poorly on the fast and rough journey over the Pacific. Such fabric was replaced with washi, a much thicker and tougher paper made from mulberry bushes. Unfortunately, washi was only available in squares about the size of a road map, requiring it be glued together using konnyaku (“devil’s tongue”) paste. The paste wasn’t cheap, and was made more expensive by the virtue of being edible – many starving factory workers would eat the paste while creating the balloons.

The balloons would carry either a small anti-personnel or incendiary bomb. The initial hope had been that the incendiary bombs would at least start forest fires, but the targeted start of the campaign, in November of 1944 due to the jet stream being at its strongest, meant these fire bombs would hit the Western U.S. during winter. Any fires the bombs might start would likely be limited by the surrounding snow. The Japanese would have to hope for the bombs sowing more confusion than damage.

—

At first, no one could quite make sense of what they were seeing.

Strange objects were seen in the air throughout the Western U.S. and Canada. Explosions were heard in the countryside. Parts of balloons were found in the streets of Los Angeles. As far east as Detroit, average Americans were coming across bizarre balloons with Japanese writing on them. The damage from such explosions was minimal – neither people nor property were being hurt. Newsweek reported in their January 1st edition about the mystery balloons, but otherwise there was little press coverage.

The media silence was by design. If average Americans weren’t terribly troubled by the balloons, the U.S. government was nearly in panic.

Most of the concern centered around how exactly the balloons were arriving in the U.S. Fears of Japanese-American saboteurs, either from internment centers or from those who had somehow avoided the camps, dominated early U.S. intelligence on the matter. Some of the fears were based around knowledge of Japan’s infamous Unit 731 and their experiments with biological warfare. If the Japanese could get balloons into the U.S., why not a balloon filled with plague fleas? The findings of the Military Geology Unit of the United States Geological Survey of the sandbags from the balloons that the sand had to come from Japan itself didn’t allay many government fears.

The lack of American media reporting on the balloon bombs didn’t stop the Japanese from claiming a major victory. Tokyo media reported that thousands of bombs were raining death and destruction on American cities, claiming thousands of American lives. In truth, of the 9,300 known balloon bombs released from Japan, only an estimated 900 even reached North America. The news of only one balloon bomb that harmlessly fell in Wyoming before the media blackout, ever reached Tokyo.

Although the balloons found few targets (one forest fire was confirmed to have been started by a balloon bomb), one balloon found six Americans with lethal results. On May 5, 1945, outside Bly, Oregon, pregnant 26-year old Elsie Mitchell and her husband, pastor Archie Mitchell, had taken five children from Archie’s Sunday school class out for a picnic when they came across the remains of a balloon bomb. Knowing nothing of what they were seeing (most Americans who stumbled across the bombs had no concept of the Japanese campaign), Elsie and the five children approached as Archie parked the car. No one knew if someone accidentally triggered the weapon or not, but the balloon exploded. Elsie and five children, all around 11 to 14 years of age, were killed instantly. Their deaths were the only ones as a result of direct enemy action in North America during World War II.

Reviewing the incident, the military concluded Elsie Mitchell and the children might have been saved if the public knew to avoid any downed balloon bombs. The media blackout was quickly lifted.

News of the deaths mattered little in Japan – the balloon campaign had been canceled a month earlier. As best the Japanese could tell, the expensive and time-consuming undertaking had been a complete failure. Coupled with the destruction of several hydrogen plants needed to inflate the balloons, the project was abandoned. Other concepts of hitting the U.S., such as Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, a proposed effort to drop plague fleas by plane over San Diego, were proposed but never carried out as Japan’s military funneled all resources into making the defense of the homeland as potentially costly as possible for the Allies.

The “fire balloons” true legacy might be their occasional discovery even into the modern age. Numerous balloon remains have been found over the decades, including one in British Columbia as recently as October of 2014.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.