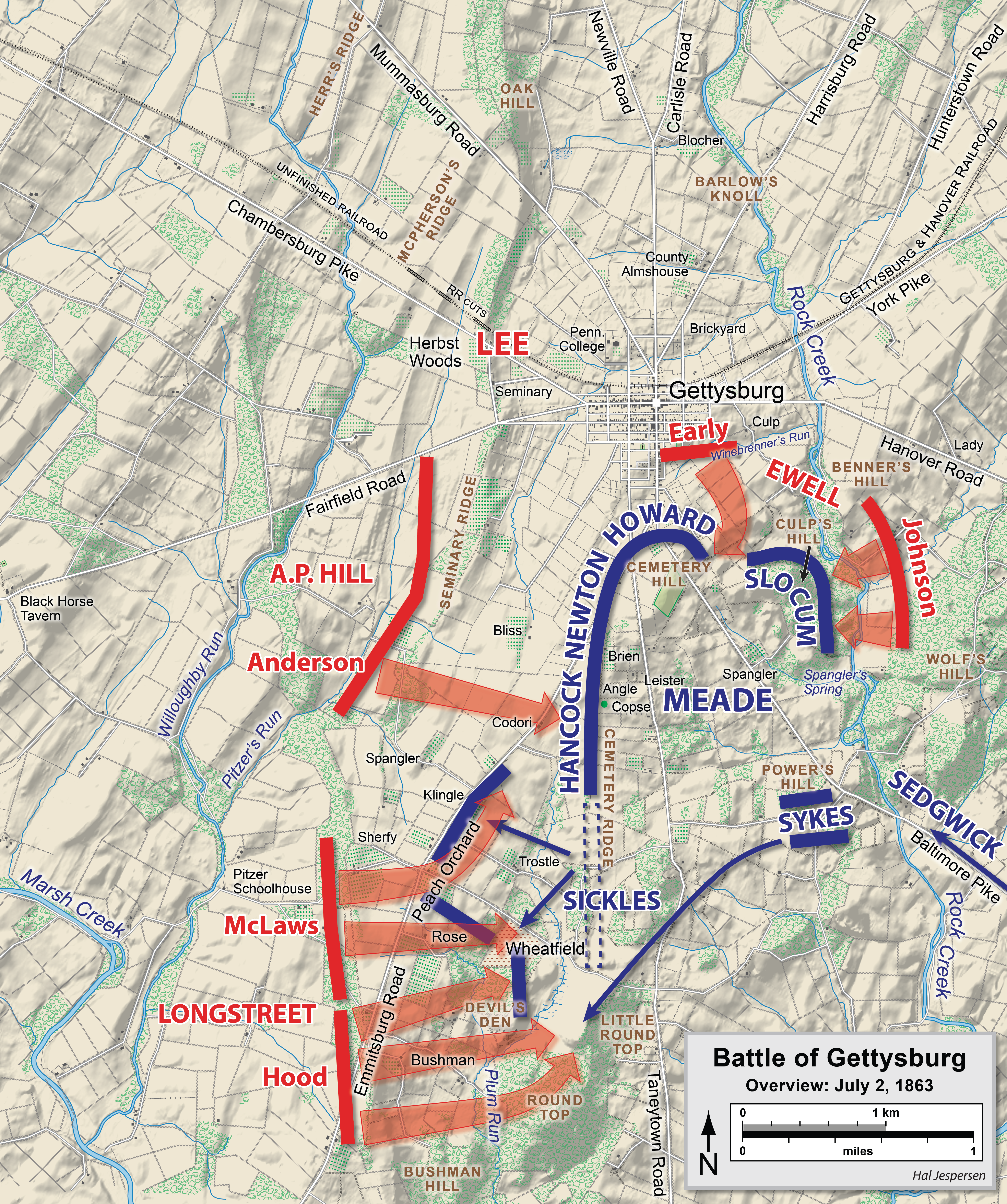

It was 150 years ago today, as the Battle of Gettysburg wound into its second day, that General Winfield Scott Hancock, commander of the Union II Corps, saw that the neighboring III Corps under flamboyant General Daniel Sickles had moved forward without communicating Sickles’ intentions to Hancock, leaving a yawning gap in the lines between II and III Corps as a Confederate force was moving toward the area. Left open (and it would be left open; Sickles’ corps, exposed in open ground, was mauled and rendered nearly combat-ineffective in a matter of minutes), the gap gave the Confederates a wide-open shot at taking Cemetary Ridge, which would break the Union defensive line.

Hancock knew reinforcements – 20,000 men from V and VI Corps – were on the way, hoofing it in from the north and east. But he needed to buy time.

He ordered the nearby First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment to charge into the gap and drive off the encroaching Confederate brigade until help could arrive.

We’ll come back to that.

———-

To people whose understanding of the US military comes from its post-Spanish-American-war form, the Army before about 1914 is a confusing enigma that reflects American political sentiments that started after the Revolution.

The “United States Army” in 1861 was a relatively tiny regular force of long-service career soldiers. Confoundingly, the “US Army” as a whole played very little role in the Civil War; it mostly guarded major federal installations, Washington, and the frontier (including a garrison at Fort Snelling). With the exception of artillery units and a few specialist units (signallers, telegraphists, some logistics units, and a couple of elite “Sharpshooter” regiments, who were analogous to today’s Airborne Rangers and which were very active in the early years of the war), the US Army played little part in the Civil War.

The bulk of the Union Army (and, likewise, the Confederate Army, which was organized on similar principles) was made up of the mass of “volunteer” units raised by the states, and then tendered to the Federal government for periods spelled out in the various units’ terms of enlistment.

One of those units – the First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment – put together from ten companies, each of around 100 volunteers from towns around sparsely-settled frontier Minnesota. The companies were:

- “A” and “C” Companies (Captains Alexander Wilkin and Wiliam Acker) from Saint Paul

- “B” Company , Capt. Carlyle Bromley, Stillwater.

- “D” Company, Captain Henry Putnam, from Minneapolis.

- “E” Company, Captain George Morgan, from the then-independent city of Saint Anthony, which would one day become Northeast Minneapolis.

- “F” Company, Captain William Colvill, Red Wing.

- “G” Company, Capt. William Dike, from Faribault.

- “H” Company, Dakota County (Hastings), under Captain Charles Adams.

- “I” Company, from Wabasha, under Capt. John Pell.

- “K” Company, from Winona, commanded by Captain Henry Lester.

In those days, commanding a volunteer unit – as a captain with a company, or a Colonel in charge of an entire Regiment – was good for immense name recognition, so many politicians called in markers for the charter to commission regiments of their own. Junior officers and non-commissioned officers – the captains, lieutenants, sergeants and corporals – were usually elected by the men. Military experience was by no means a prerequisite.

The First Minnesota was fortunate to to have been organized by Colonel Willis Gorman. A 45-year-old self-taught lawyer from Kentucky who’d been a five-term Indiana congressman, Gorman had left Congress to volunteer as a private in the Third Indiana Regiment to serve in the Mexican-American war; he’d been promoted to First Sergeant by the end of his one-year enlistment, and elected Colonel of the new Fourth Indiana in his next year. That’s right – from private to full colonel commanding a regiment in under two years. Gorman led the Fourth Indiana in the capture of Mexico City. After the war, he returned to law and politics, including two more terms representing Indiana in Congress, followed by four years as governor of the pre-statehood Minnesota Territory. After statehood, he remained in Saint Paul, building a law practice until the start of the Civil War.

As the war started, Gorman raised the First Minnesota.

And by a fluke of fate, as Gorman was mustering the ten companies from around the southeast part of the state into a regiment, Governor Alexander Ramsey was in Washingon on business with President Lincoln. Getting news of the commencement of hostilities and of Gorman’s new unit, he was the first of the Union state governors to offer his state’s troops to the Federal government for service in the new war; he was literally in the right place at the right time.

So the First Minnesota was, in fact, the first unit in the vast army that would, over the next four years, fight the bloodiest conflict in American history.

Gorman was not a popular officer with his men, initially – but by all accounts, he ran the First Minnesota like a military unit – which was by no means a given in the vast army of volunteers that was forming. Having been in combat, Gorman was remorselessly professional, and demanded the same from his officers and men. He worked relentlessly, according to the history of the unit, to drill into his men not only the rote tactics of the day, but the esprit de corps that so often separates the successful military unit from the pack of uniformed rabble.

This paid off at the unit’s first engagement, the First Battle of Bull Run. The battle – in the no-man’s-land between the duelling capitols of Washington and Richmond – was a rout, with most of the Union army, commanded by their inexperienced officers and elected NCOs, breaking and running away. The First Minnesota distinguished itself by being the one of the last Union units to leave the battlefield, and one of the few to leave it in good order – as an organized fighting line, rather than a panicked mob. Indeed, the other two regiments in its brigade had run away, leaving the Minnesotans to carry on alone, suffering among the heaviest casualties (49 dead, 107 wounded) of any regiment in that first disastrous battle. Gorman was promoted to Brigadier General after Bull Run.

More casualties – 16 dead and 94 wounded – followed at Antietam, in 1862.

But it was 150 years ago today that the Regiment earned its place in history.

———-

The story is being told all over Minnesota, in all sorts of media, today; General Hancock, seeing General Sickles’ III Corps moving forward, and then retreating in disorder, and the brigade of Alabama troops under Brigadier General Wilcox approaching, grabbed the only organized troops he could find – eight companies of the First Minnesota, with 262 men – and ordered them to charge at the 1200-strong Alabama brigade, to try to buy enough time for reinforcements to plug the gap.

The Regiment – led by John Colville, who’d started the war as the captain in charge of Company F, been promoted to Major after Bull Run and Lieutenant Colonel and second-in-command in time for Antietam – set off at double-time, with bayonets fixed.

The Alabamans blazed away at the Minnesotans, who pressed the attack home with a ferocity that sent the larger force reeling, even though outnumbered by 5:1. Brigadier General Cadmus Wilcox, the Confederate general, wrote in his official report a few weeks after the battle (I’ll add emphasis):

“This stronghold of the enemy [i.e., Cemetery Ridge], together with his batteries, were almost won, when still another line of infantry descended the slope in our front at a double-quick, to the support of their fleeing comrades and for the defense of the batteries [he’s referrring to artillery, here – Ed].

Seeing this contest so unequal, I dispatched my adjutant-general to the division commander, to ask that support be sent to my men, but no support came. Three several times did this last of the enemy’s lines attempt to drive my men back, and were as often repulsed. This struggle at the foot of the hill on which were the enemy’s batteries, though so unequal, was continued for some thirty minutes. With a second supporting line, the heights could have been carried. Without support on either my right or left, my men were withdrawn, to prevent their entire destruction or capture. The enemy did not pursue, but my men retired under a heavy artillery fire, and returned to their original position in line, and bivouacked for the night, pickets being left on the pike.”

The charge drove back a force five times the size of the First. It bought the time needed for Hancock to get the reinforcements into the line and consolidate Cemetary Ridge.

And the First Minnesota stayed right there; the 47 men still standing (along with F company, which had been on detached duty on July 2, and missed the charge, bringing the “regiment’s” strength back up to around 80) were waiting when Lee launched General Pickett’s division on its ill-fated charge up the ridge the next day, July 3, the “High Water Mark of the Confederacy”. At it was here, where the First was stationed, that Picket’s charge came closest to success; part of Pickett’s division reached the Union line, and spilled through; once again, a counterattack by the First Minnesota (commanded now by Captain Coates, who’d started the war in “A” Company) drove back the Rebel spearhead. Private Marshall Sherman of “C” Company captured the battle flag of one of the attacking units, the 28th Virginia, winning the Medal of Honor (one of two for the Regiment that day; the other went to Corporal Henry O’Brien, who, wounded in head and hand, picked up the First’s fallen flag under ferocious fire. The Minnesotan kept their flag, and the Virginians’ as well. It remains in Minnesota to this day, at the Minnesota Historical Society, the subject of some controversy between Minnesota and the Commonwealth of Virginia.

The regiment served until the following April, when its enlistment ended. Most of the volunteers served in other Minnesota units for the rest of the war; Colville became a legislator.

It’s amazing, the number of First Minnesota veterans who went on to prominence in the new state after the war. This roster site has a fascinating list of biographies of an amazing number of First Minnesota veterans. It’d be a fun game to see how many of these men have streets named after them in your community.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.