My ex father-in-law, Al, had been married about a week when Pearl Harbor was attacked. The next morning, he and his umpteen brothers (I lost count and never really found it again) volunteered for one of the armed forces or another (except for one older brother who had already joined the Navy in the thirties).

He had a busy war.

As I recall the story; he started off working as a cook, then trained as a gunner’s mate. He shipped aboard theUSS Iowa, and cruised to North Africa to take FDR to the Casablanca conference.

Then, when cleaning his gun (a 20mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft machine gun), a recoil spring popped loose, catapulting him over the edge and down a deck or two, cracking a vertebrae or two. He was in the Naval Hospital for months recuperating from the injury, as Iowa sailed on.

And so he was reassigned to “new construction” at Bath Iron Works in Bath, Maine, upstream from the Atlantic along the border with New Hampshire – a shipyard that still builds all the US Navy’s destroyers.

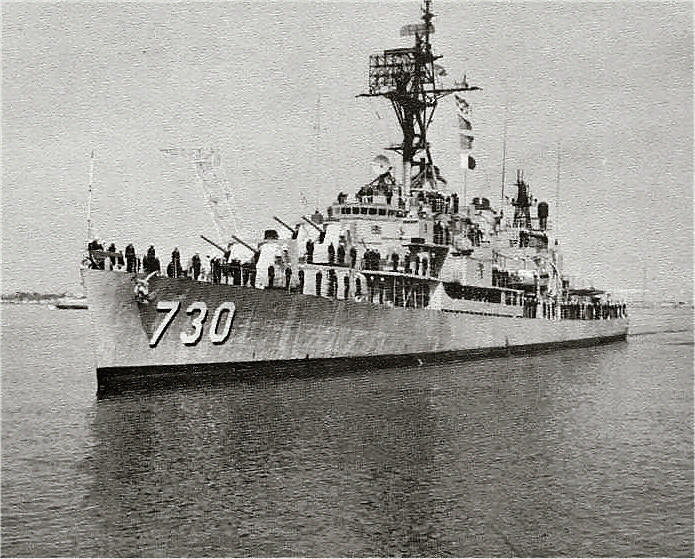

He was assigned to the fitting-out and commissioning of a brand-new destroyer – DD-730, to be christened the USS Collett. The destroyer was named after Navy Lieutenant Commander John A. Collett, commander of a torpedo bomber squadron who’d been shot down and killed at the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands in 1942. In a highly unusual non-coincidence, the ship’s first commander was Collett’s brother, Commander James D. Collett.

And seventy years ago today, Collett was commissioned into the US Navy. Al was a “plankholder” – a member of the crew that put the vessel into service.

Collett was an “Allan Sumner” class destroyer – the first class of US Navy destroyers designed entirely after the war started. With six five-inch guns in three turrets (instead of the four or five single turrets of earlier designs, all capable of shooting at either ships or aircraft), and twelve 40mm anti-aircraft machine guns, the Sumners reflected the lessons learned so far in the war; anti-aircraft firepower was a matter of life or death. As indeed for the Collett it would be shortly.

After its shakedown – a fast, wartime working-up period – Collett set sail to join the Pacific Fleet, arriving in Pearl Harbor exactly five months from its commissioning date, and at the massive forward base at Ulithi Atoll three weeks later.

And then it was off to war.

Two weeks later, she was off to start in the run-up to the invasion of the Philippines. And there – on November 14 – Collett was part of an extraordinary encounter. The destroyer was posted on radar “picket” duty – sailing well north of the main invasion fleet, to provide early radar warning of incoming air raids. It was among the most dangerous jobs in the Navy; the Japanese knew what the long chains of lone destroyers were doing. Of course, the carriers provided air cover – but it didn’t always work.

Destroyers – even big ones like the Collett – had their limitations. The general assumption was that one destroyer could take on one attacking aircraft at a time. That wasn’t chicken feed; an incoming combat aircraft flown by a competent pilot is a formidable target. And while the fire control systems on American destroyers were wonders of analog technology – by far the most advanced of their day – the complexity of the problem generally boiled down to the simple fact that a destroyer could reasonably hope to deal with one attacking aircraft at a time. (Larger ships – cruisers and battleships – could deal with more, and a formation of ships escorting an aircraft carrier could put up a storm of anti-aircraft fire that made attacking a US formation a very risky, costly thing by 1944. Indeed, a kamikaze mission. But we’ll get back to that).

On November 14, four Japanese G4M2 “Betty” torpedo bombers approached Collett.

Seventy years of being the victors in the war have given Americans a sense that Japanese military equipment was junk – but in fact the “Betty” was one of the better torpedo bombers of the war. It was fast (for a twin-engined bomber), with an extremely long range, and armed with Japanese torpedoes (and unlike American torpedoes, Japanese torpedoes were excellent, accurate, and utterly reliable), the “Betty” was a formidable plane. And there were four of them.

And they were clearly led by a competent tactician, because the four planes fanned out around Collett, turned, and came in from all four points of the compass – a tactic that virtually ensured that at the very least three planes and likely all four would get to drive their attack home, that three or four torpedoes would be launched, and at least one would almost certainly hit the target, definitely crippling it, probably sinking it.

But the American ship – Commander Collett and his anti-aircraft crews, including Al, who was the gun captain of a 40mm mount to starboard of the forward smokestack – pulled off an incredible performance, shooting down two of the incoming bombers. In those days, it was an amazing display of gunnery.

The other two launched their torpedoes – and, in a feat of seamanship that sounds pretty trival in written English, but which in practice was a couple steps shy of parting the Red Sea, Commander Collett managed to “comb the wakes” of the two incoming “fish”, dodging them both.

The feat may have stopped short of “miracle” – but it was an exceptional display of gunnery, seamanship, and 1940s analog computing technology.

The Collett – and Al – went on to much more; they battled Kamikazes off Okinawa. Its’ squadron was among the first American ships to sortie into Tokyo Bay, torpedoing several Japanese merchant ships in the process. She escorted the Missouri to the surrender ceremony.

And that wasn’t all. She fought in Korea – Collett was the second ship into Inchon Harbor, battling it out with the Korean shore batteries, among a group of destroyers that were expected to be “sitting ducks“, drawing North Korean fire to mark the guns for obliteration from fleet gunfire and air attacks. In fact, the destroyers silenced the Korean guns, and Collett suffered light casualties.

She was an active unit of the Pacific Fleet until 1960, when she collided with the USS Ammen, had her bow replaced with the bow from another WWII destroyer, and then served off Vietnam.

Then, in 1974, she was sold to Argentina. The USS Collett became the Argentinian navy ship ARA Piedra Buena.

During the Falklands Islands war of 1982, Piedra Buena was escorting the Argentinean cruiser General Belgrano (formerly the US light cruiser Phoenix) when the Belgrano was torpedoed by the British submarine HMS Conqueror. Piedra Buena picked up survivors, then returned to Argentina.

The ship’s long career ended in 1988, when the Argies sank her as a missile target.

That, as it happens, was maybe a year before I met Al.

Like a lot of WWII vets, Al apparently didn’t talk a lot about the war (or so his various kids told me). In 1990, out of ideas for Christmas presents, I built a small scale model of Collett, and mounted it on a plaque with a couple of wartime photos of the ship.

After that, he started talking a little more about the war; he dragged out his old blues, and some of his photos, and some of the stories. He passed away about ten years back. Unlike a lot of ex-in-laws, Al and I always got along famously.

Apropos not much. I just noticed the anniversary.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.