It was well after 2:00am on May 7th, 1945 when the first cars pulled up to a little red schoolhouse in Reims, France.

Shuffling inside, and out of the cold morning air, were representatives of most of the major combatants in Europe. Few were major commanders – the closest being Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, the chief of staff of Gen. Eisenhower. Accompanied by the Soviet liaison officer Ivan Susloparov and French Major-General François Sevez, the Allies awaited their guests.

Arriving in an Allied-driven staff car, Generaloberst Alfred Jodl and his staff entered the schoolhouse. Given the assignment of representing the German government by Admiral – and now, with the suicide of Adolf Hitler, President – Karl Dönitz, Jodl had arrived two days earlier with simple instructions – negotiate a surrender to the Western Allies only. Eisenhower had made it clear to Jodl just hours earlier that only a complete unconditional surrender would be accepted. Otherwise, Eisenhower would order the Western Front “closed” to German surrender, forcing the Nazis into the waiting arms of the Soviet Army. Neither Dönitz or Jodl wished that fate.

At 2:41am on May 7th, 1945, Nazi Germany agreed to unconditionally surrender by the following day, May 8th. The war in Europe was finally about to end.

—

The events of May 7th/8th were the culmination of numerous, “smaller” surrenders over the preceding weeks.

1.5 million German troops had surrendered to the Western Allies in April alone. On May 2nd, an additional 1 million members of the Wehrmacht surrendered in Italy and Austria. Coupled with the 800,000 POWs the Soviets had captured in the war’s waning months, what was left of the once fearsome Wehrmacht was literally disintegrating.

Germany’s soldiers might no longer have been much of a threat on the battlefield, but as prisoners they were a serious threat to the Allies’ supplies. Still operating on an extended supply chain from Antwerp following the Battle of the Bulge, the Allies quickly found themselves responsible for millions of undernourished men, women and children. In addition to the millions of POWs, the Western Allies had to manage nearly 9 million displaced persons in Germany and Austria, millions of recently liberated slave laborers, and 14 million ethnic Germans the Soviets had forced out of Eastern Europe.

Despite the Allies’ supply largesse, there simply wasn’t enough food to go around. The Soviets had a simple solution to their part of the problem – starvation. Hundreds of thousands of German POWs officially died while under Soviet guard. Unofficially, the number might be horrifically higher as 1.3 million German POWs are still classified as “missing.”

The Allied solution was more bureaucratic, but it had a similar end result. Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, prisoners of war were entitled to medical care and rations. Unable to provide both on the scale necessary to met the Convention’s standards, the Allies reclassified the Germans soldiers under their care to “disarmed enemy forces” – a term that implied that such forces needed to supply their own food and medicine, and could. Millions of German troops were stuck in a legal no-man’s land – neither fully a prisoner nor free man, and thus neither eligible for supplies nor able to procure them.

An estimated 790,000 German soldiers would die in the West (the exact figure is unknown and highly debated). Counting the official and unofficial losses from the East, plus those who already perished in combat, perhaps as many as 6.37 million German troops died within the Second World War.

—

The German Army was desperate to surrender. The only question was who was in charge enough to do so?

Nominally it was Karl Dönitz – who had been granted the post of Reichspräsident and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces in Hitler’s last will and testament. Dönitz had taken the post pretty much by default. Hermann Göring or Heinrich Himmler would have been logical choices for a successor, but in his final hours, Adolf Hitler believed both had betrayed him – Himmler by attempting to surrender to the West (his offer was declined) and Göring by insisting on the title before Hitler was ready to relinquish it. In Hitler’s mind, only the Kriegsmarine had not undermined the war effort and thus the Navy’s supreme commander should take over control of what was left of the German nation.

With the fall of Berlin, Dönitz relocated the government to Flensburg on May 2nd, where he attempted to piece together some form of government to be able to officially surrender. His first challenge was to convince his would-be rivals that the mantle of command had passed to him.

Göring had already been arrested – one of the last acts of Hitler’s control – but Himmler remained free. The head of the SS requested a meeting with Dönitz in the wake of Hitler’s suicide, arriving with six SS soldiers. Dönitz would later recall hiding a pistol underneath some paperwork on the desk where they met – half expecting that Himmler and his men would attempt to assassinate him. Instead, one of the most feared men in one of history’s most terrifying regimes was reduced to begging Dönitz for a role in whatever government the former Großadmiral intended to form.

The answer was a firm “no.” Dönitz had hoped that by not appointing Himmler and others into his Flensburg government that the Western Allies would prove lenient. Perhaps even with Hitler gone, Germany could negotiate a separate peace with the West.

It was not to be. By May 23rd, Dönitz’s brief reign was over – Eisenhower had the Flensburg government disbanded and arrested. Unlike the end of the Great War, there would be no distinction between the civilian and military leadership of Germany. Germany’s surrender was to be complete – with no exceptions.

—

An end to the war didn’t mean an immediate end to the fighting.

While most German Army units followed the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht orders to surrender, others held out. Axis forces on scattered Greek island announced their intentions to surrender on May 9th. The German troops on the Channel Islands between England and France – the only part of the English Isles to be occupied during the war – drew out their eventual surrender for several days. Troops on the Channel Island of Alderney didn’t allow British troops to take them prisoner until May 16th.

Not all prolonged surrenders were so bloodless. On the tiny Dutch island of Texel, members of the Georgian Legion rebelled against their German allies, killing 400 while they slept in their barracks. The Georgians were largely Soviet POWs and a handful of émigrés who had fled Georgia after the Soviet invasion in 1921. The Legion assumed the Allies would assist them if they liberated the island. They did not. Instead, the Germans reoccupied Texel, slaughtering the Georgians and those Dutch civilians who tried to shelter them. The fighting didn’t end until May 20th as a Canadian occupation force negotiated a German surrender. The delay cost, in part, the lives of over 550 Georgians and 120 Dutch civilians.

Texel looked quaint to the scale of the largest “post-war” battle in Europe – the occupation of Prague.

The Czechoslovakian capital had been prized by all the warring parties – for its current and post-war value. The largest remaining German army in Europe, Army Group Centre and the remains of Army Group Ostmark, with nearly 1 million troops, was headquartered at Prague. In addition, possession of the capital would likely highly influence Czechoslovakia’s post-war politics. Despite Winston Churchill’s impassioned pleas for U.S. forces to strike towards the city before the Soviets could capture it, American forces pulled up short, allowing nearly two million Soviet and Soviet-allied soldiers to launch their invasion on May 6th, 1945.

The crushing weight of Soviet arms, and a massive uprising of Czech civilians (due in part to the mistaken belief that the American army was about liberate Prague), made the next 5 days what surviving German veterans would call the “Czech Hell.”

Not unlike most of the units in the German army, Army Group Centre had hoped to be able to surrender to the Americans. But with the group’s command center captured by May 8th, the ability to coordinate anything, including a surrender, was lost. Haphazardly, German troops attempted to fight past Soviet soldiers and engaged Czech partisans to get to George Patton’s U.S. Third Army. German Field Marshal (and Waffen SS leader) Ferdinand Schörner didn’t make it any easier on his troops – vowing to crushing the Prague uprising in “a sea of blood” while committing atrocities against the local population.

By May 11th, 1945, the fight for Prague was over. Amazingly, 860,000 soldiers of Army Group Centre managed to surrender. Unfortunately, most of those who surrendered did so to the Soviets. Few would come home.

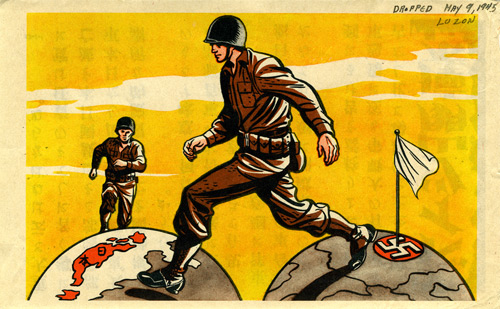

The last remnants of the Nazi Germany had been defeated. While Japan remained unbowed – for the moment – the most destructive conflict in human history was nearly over.

—

In practicality, peace had arrived. Legally, or diplomatically, it hadn’t. Not yet.

The German government had been abolished, leaving a myriad of legal conundrums as to how the Allies should (or could) proceed as victors. Beyond the haunting legacy of Versailles, the Allies wanted to establish as much of a legal basis for their continued occupation. As such, technically a state of war continued to exist between Germany and the Allies for years to come.

Not until 1950, in an effort to strengthen the legitimacy of West Germany, did the United States, Britain and France finally decide to “end” World War II (the Soviets did the same in 1955). American soldiers manning the new front line in the Cold War were now no longer occupiers but allies. Germany might have had it’s own government again, but it remained divided and limited in the control of it’s own territory (as in the case of East/West Berlin).

Only with the reunification of Germany did the country fully regain sovereignty in 1990. The Four Powers who divided Germany – the U.S., Soviet Union, Britain and France – all renounced their right to occupy German territory. It had taken nearly 46 years since the guns in Europe fell silent.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.