Today’s story ties together a bunch of my favorite themes; Epic Historical Events that happen as a series of happenstances and blunders; second-chance redemption stories; untold stories of great significance.

But most of all, it’s the story a maritime people sweeping the seas of their foes.

The maritime people, in this case, is North Dakotans.

We Come From The Land Of The Ice And Snow: Joseph Enright was born in 1910 in Minot, North Dakota.

He graduated from Annapolis, spent three years on the battleship USS Maryland, and then transferred to submarines, qualifying as a sub officer in 1936. As the Navy, and especially the submarine service, grew frenetically before World War II – part of FDR’s version of “shovel ready jobs”, as well as getting ready for the war everyone on both sides of the Pacific knew was inevitable – Enright moved up fast, serving on the crews of the World War I-vintage subs S-35 and S-22; not long after the war started in 1942, with a new promotion to Lieutenant Commander, Enright was given command of an even older boat, the USS O-10, a predecessor of the S-boats, used as a training ship.

.jpg/300px-USS_O-10_(SS-71).jpg)

The early years of the war were tumultuous ones in the submarine service; equipment problems dogged American submariners’ efforts for the first 18 months. It didn’t take long for a combat command billet to open up for Lt. Commander Enright; he assumed command of the brand-new USS Dace.

Take Me Out, Coach: He took command of the boat in July of 1943. By November, he had the boat worked up and ready for action. The boat’s first war patrol took it into Japanese home waters.

On November 15, a few weeks into the patrol, directed by an intercept from the US Navy’s “Ultra” cryptography unit, Enright and Dace were directly in the path of the Japanese aircraft carrier IJN Shokaku, one of two surviving carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor. Enright made contact with the carrier’s task group – a powerfully-escorted force, dangerous to attack – but couldn’t quite maneuver into position by daybreak; in his own report, he described having made a “timid approach, breaking off as daylight approached”. Later in the patrol, an attempt on a Japanese tanker ended with a sound depth-charging at the hands of Japanese escort ships.

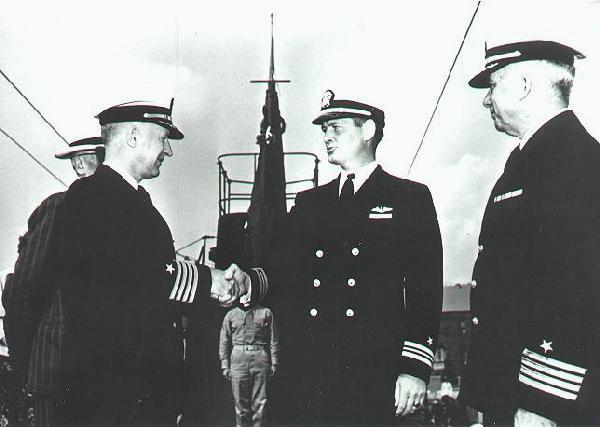

The seven week patrol ended with no sinkings. Disappointed in his own performance, Enright asked to be relieved of command. Admiral Lockwood, the crusty submariner who commanded all US subs in the Pacific, obliged, as he had not a few earlier officers who’d decided they didn’t pack the gear. Enright was assigned to administrative duties at the Midway Island submarine station.

And with most officers relieved of a combat command, that’s where it would have ended.

Redemption: After six months of administrative penance, Enright asked Lockwood for another shot.

Incredibly, Lockwood said yes, assigning him to command the USS Archerfish.

Archerfish had had almost as disappointing a war as Enright so far. In four war patrols, they had attempted three attacks, for zero kills. They hadn’t even seen a ship on two patrols, and had spent one patrol on “lifeguard” duty off Iwo Jima, rescuing one shot-down naval aviator from the water.

And so in October, Enright took Archerfish out on its fifth war patrol. From November 11 to November 28, the boat cruised off the Japanese coast not far from Tokyo, on “lifeguard” station again – cruising in a small, fixed area that damaged American B-29 bombers could get to if they were too badly damaged to make it back to their airbase on Saipan.

With the cancellation of the day’s strikes on November 28, Archerfish was cut free from lifeboat duty, and was free to patrol.

And there, toward dark, his lookouts spotted what they originally thought to be a Japanese tanker, with an unusually heavy escort of three first-line destroyers, leaving Tokyo Bay.

Enright and his officers soon figured out it was actually an aircraft carrier; the ship was moving at a good clip, zig-zagging toward the south. The officers worked out the math, and moved Archerfish as fast as its 20-knot surface speed could manage, to get it into position for a shot at the one point in the zig-zag they could intercept.

After six hours of maneuvering – much on the surface, but the last stretch underwater to avoid detection – the ship zagged into Archerfish’s path. Enright ordered all six of the boat’s forward torpedo tubes fired, and watched as the first torpedoes hit and the ship began to list, before ordering the boat deep to avoid a depth-charging.

Four of Enright’s torpedoes hit the ship. Although Enright never did see the final outcome, his sonarmen could hear the sound of internal compartments rupturing, the unmistakeable sound of steel ripping and crumpling. They knew they’d drawn blood.

They returned to Pearl Harbor, claiming an aircraft carrier. The Navy staff was certain it had to have been a cruiser; they were pretty sure there were no surviving Japanese aircraft carriers in the area. They grudgingly credited Enright and Archerfish with a light carrier after Enright sketched what he’d seen through the periscope in great detail.

The Big Kahuna: They were both wrong.

The ship was the IJN Shinano, at 70,000 tons the largest aircraft carrier ever built.

The ship had started life as a sister ship to the Japanese battleships Yamato and Musashi, the biggest battleships ever built to this very day. As it became clear that the age of the superbattleship had ended and the aircraft carrier was here to stay, the Shinano was converted into a large aircraft carrier. It retained much of its battleship structure, including armor.

It had been built under complete secrecy, so paranoid that most of the Japanese fleet knew nothing about it; built in a covered drydock, by workers sworn to secrecy on pain of death by beheading, with no mention of it ever made on the radio or any other medium that the Allies could monitor. It was the only major warship of the 20th century never to have an official construction photograph. Shinano was in fact a complete surprise to the Allies – so complete, in fact, that they didn’t believe what Enright had sunk until they looked at records after the war.

It was the largest aircraft carrier ever built (until the American supercarriers of the 1950s through today). It was the largest ship ever sunk by a submarine – and one of the largest ever sunk in combat, period (only its half-sisters, Yamato and Musashi, were bigger).

The moral of the story?

Forget F. Scott Fitzgerald; America is all about second acts. Enright came back from palookaville to score one of the biggest notches in the history of naval warfare.

And watch out for North Dakotans. We’re a maritime people.

And we know how to break things.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.