For three and a half years, President Woodrow Wilson had envisioned himself as Europe’s peacemaker. From the earliest days of the conflict, through and even beyond his re-election campaign, Wilson had repeatedly held himself out as a potential mediator. The President had taken a number of steps to try and intervene in Europe’s war, including trying to negotiate aid to starving Polish refugees on the Eastern Front and even drafting a peace memorandum which was delivered to the Entente in February of 1916.

The interest from Europe was not reciprocated. The Germans and Russians had no interest in American aid to Polish citizens and the British and the French believed Wilson’s 1916 memorandum was little more than an election-year stunt. To the rulers of Europe’s warring parties, the American President was either woefully naïve about the nature of the conflict or deeply politically cynical. Wilson’s push for “peace without victory” had no support among the war’s leadership, but Wilson did raise a consequential point for the populaces of Europe – why was the war being fought in the first place? And what did the combatants hope to get out of it?

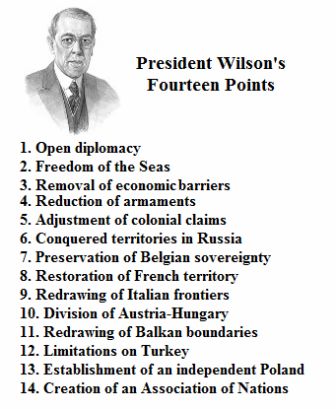

On January 8th, 1918 before the U.S. Congress, Wilson would provide an American answer to the question of Europe’s conflict – fourteen points upon which peace, and a post-war world, could be built.

Part of the roots of the end of the conflict were laid with Wilson’s “Fourteen Points.” Germany assumed the Allies final peace terms would mimic the less punitive terms of Wilson’s address

By the beginning of 1918, it had become apparent for Europe’s nations that support for the Great War – among civilian and soldier alike – had all but vanished. Revolts, rebellions, mutinies and food riots had increasingly become standard as Europeans were demanding peace, or at least a worthy cause to explain the hardships they had endured. The war’s leaders had no real response.

The empires of the Central Powers had attempted to ignore their own deteriorating condition. Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans had fallen victim to internal conflict, with numerous nationalities looking for autonomy and finding only a firm hand from their nation’s political leadership. Franz Joseph had dismissed the polygot empire’s Diet and the Turks were being pulled in varying directions by the “Three Pashas” who were crushing the constitutional ideals that animated the Young Turks rebellion just years earlier. Even Imperial Germany, which had a functioning legislature, essentially ignored the demands by their own parliament to seek out peace terms with the Entente.

The Allies were hardly any better. Despite his country nearly falling from the mutinies of the spring of 1917, newly appointed French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau declared his new government’s policy was “la guerre jusqu’au bout” (“war until the end”). David Lloyd George, who on the war’s eve had implored his fellow members of parliament to avoid a fight with Germany, now declared that the only acceptable conclusion of the Great War was a “knockout.” Politicians and certain members of the press cheered such proclamations. But without victories – or guiding policies – the words risked ringing hollow.

David Lloyd George – while George’s address would carry similarities to Wilson’s “Fourteen Points,” the underlying motivations would be vastly different

For all of it’s anarchy, the Bolshevik revolution in Russia had appeared as the only counter argument to Europe’s steadfast resolve to continue the war. Worse for the Allies, the Bolsheviks had released troves of secret communications and agreements, such as the Sykes-Picot Agreement, demonstrating that for Europe’s leadership, the war was ostensibly being fought to solidify and expand their colonial empires. Millions dying to protect Belgian independence seemed noble; millions dying to occupy vast tracks of African lands or obscure Arabian ports seemed a cruel joke of the sacrifice. With such a backdrop, Lenin’s “Decree for Peace” in November of 1917 might have been unrealistic, but suggested a path forward based upon peace and self-determination – a goal and a principle that neither the Allies nor Central Powers had articulated or supported.

Wilson was determined to counter the Bolshevik manifesto with what he believed was a more detailed, and more realistic, appeal to a post-war world dictated by Wilson’s progressive and religious morals. In doing so, Wilson hoped to steer the entire Allied cause.

Wilson practically had his thunder stolen from him before he even spoke. On January 5th, 1918, David Lloyd George gave an address outlining Britain’s war aims. It would sound surprisingly like Wilson’s upcoming address.

The “Fourteen Points” would resemble the Allied call for “unconditional surrender” a conflict later; they became the rallying point for the Allied war, even if most of the Allied leaders disagreed with Wilson’s terms

Although the address held much of George’s usual bluster – “we mean to stand by the French Democracy to the death” – it also sounded conciliatory to Germany in parts and downright Wilsonian in respect to self-determination. “The days of the Treaty of Vienna are long past,” George declared, citing the Congress of Vienna more than 100 years earlier that had carved up the map of Europe with the input of only royalty and a handful of foreign ministers. While George’s views on self-determination were largely in regard to smaller occupied nations like Belgium, Serbia and Romania, the British PM applied the principle even to Germany’s former African territories. “Government with the consent of the governed must be the basis of any territorial settlement in this war,” George intoned.

George had intended his speech to serve a similar purpose to Wilson’s upcoming address – countering the Bolshevik “Decree on Peace.” But whereas Wilson would attempt to set the terms for the future, George was seemingly more interested in litigating the past, repeatedly arguing that the Central Powers had yet to articulate a rationale for their participation in the war outside of territorial gain. The Allies recent embrace of self-determination had, by the tenants George laid out, given them moral superiority over the “Central Empires” as he called them, thus providing a rationale for continuing to conduct the war. Other than proclaiming that the Allies had no interest in a punitive peace with Germany (which was patently untrue; the French wanted to break German power for good), George’s audience was largely a domestic one. George wanted to justify the path that had taken the Allies to this point; Wilson wanted to justify a path forward.

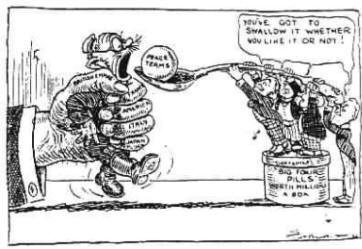

Forcing peace terms on Germany – a political cartoon of the era

For all of his desire to be seen as a mediator, Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” were, not surprisingly, titled heavily in favor of the Allies.

While fairly basic rights, such as free travel of the seas and open trade were among the points, the territorial terms were set to negate any of the Central Power’s current or past holdings. Belgian and French occupations had to end, in addition to Germany giving back Alsace-Lorraine, which Wilson claimed had “unsettled the peace of the world for nearly fifty years.” German gains in Russia had to be relinquished, the Turks had to surrender their Arabian Empire, and the Austro-Hungarians would have to give Italian-majority provinces to Rome while allowing for self-determination among their other nationalities, a move that almost certainly would lead to the break-up of the Dual Monarchy.

Most of Wilson’s points were widely supported at the time. Points related to colonial possessions and the limiting of national armaments would surely upset the other Allies, but the “Scramble for Africa” and various naval arms races had been blamed as contributing factors to the European environment that had led to the war. Some saw the inclusion of points on Russia as an attempt to bring the Bolsheviks into the international fold, perhaps tempering the worst of their revolutionary zeal to something closer to the diplomatic norms of the era. Most importantly, Wilson had created a counterpoint to Lenin, while providing a post-war template that was largely advantageous to the Allies.

The “Fourteen Points” set the impression – both domestically and internationally – that Wilson was the philosophical leader of the Allied cause. Such a perception rallied support of the war, but also increased public frustrations with the eventual peace, as Versailles held little in common with Wilson’s stated goals

But the speech – and points – had been crafted without Allied input, and created a number of significant unintentional hurdles for the post-war world. The treaty held no parameters for financial reparations for a conflict that, by 1913 dollars, would cost all parties $208 billion. Entire nations had been ruined; who would pay for the necessary economic recovery? And self-determination, while a noble-sounding goal, also meant that every ethnic group in the world saw an opportunity to establish their own nation state. Both the Central Powers and the Allies had encouraged ethnic and/or religious alliances to undermine their opponents, but how would such future nations be organized? Even an independent Polish state, which in theory all powers supported, would inevitably contain Ukrainians, Germans, Mausrians, Lithuanians and Ruthenians in addition to the Poles. Should each of those groups get a nation of their own as well?

True self-determination was shot across the bow of the two largest colonial powers in the world – Britain and France. While London and Paris understood that agreements such as Sykes-Picot would hold no favor among even their populaces going forward, neither nation was prepared to lose the economic engines that propelled their empires. The colonial holdings that defined Africa and Asia had not been established by any ethnic boundaries or self-government, would those possessions further fracture if given independence?

All fourteen points

The last of Wilson’s points would become the most controversial – the call for “a general association of nations…formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity.” International conventions were certainly a standard diplomatic practice, from the conventions surrounding the Napoleonic Wars to the Geneva Convention, but a permanent standing association was definitely new. Wilson hadn’t been the first to propose such an arrangement – indeed, President Theodore Roosevelt had articulated just such a league when he accepted his Nobel Peace Prize, calling for a “League of Peace.” Ironically, Roosevelt would harshly criticize Wilson’s League of Nations as the idea began to take form. But for the moment in January of 1918, the League of Nations was little more than an afterthought as a condition of peace.

With such weighty questions, Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” arrived with a dud in the capitals of Europe. Clemenceau mocked Wilson by privately declaring “the good Lord only had ten!” The Central Powers saw Wilson’s text as standard Allied propaganda and even American politicians derided the vagueness within Wilson’s goals. Only Lenin spoke approvingly of the address, further hurting Wilson’s hopes for broad political acceptance.

The “Fourteen Points” at once represented the best and worst of American idealism when it came to foreign policy. But Wilson’s audience had not exclusively been an American one, nor even an audience of his international political peers. Wilson’s address had been aimed squarely at international public opinion.

U.S. pushback against the “League of Nations” – American opinion would be staunchly against participation, especially in light of the Treaty of Versailles

Publicly, even if the rest of the Allies were non-committal, the Alliance now had a set of terms from which any future armistice or peace treaty could be dictated. While Germany dismissed Wilson’s address, the “Fourteen Points”, coupled with George’s early speech, suggested a path where, at most, the Germans would lose their colonial possessions and recent acquisitions in Russia. German territorial integrity would be upheld (which the exception of Alsace-Lorraine) and the Kaiser would remain in power. Victorious in the East, the Germans were disinterested in striking such terms now, but fears that the Allies might break-up the German State and/or destroy the Prussian monarchy had motivated Berlin for several years. Whether the German royalty and politicians who pushed such narratives actually believed them (there was never any evidence that the Entente or Allies were interested in undoing German unification), the “Fourteen Points” showed an enemy willing to grant a supposedly easy peace.

When Germany was eventually prepared to accept peace, they did so proclaiming acceptance of Wilson’s “Fourteen Points.” While the final terms of Versailles would drift far from the principles of Wilson’s original address, planting the seeds of the next world war and countless other conflicts, Wilson’s goals had been to steel Allied resolve around a defensible set of principles and stop the Bolsheviks from gaining any further international support. On those fronts, for all of it’s future flaws, the “Fourteen Points” succeeded.

“Reduction in armaments” was a torpedo launched below the waterline of the British navy & so the British Empire. Wilson & Roosevelt. For good or bad, Wilson and FDR dismantled the British as a world power, though it took them three decades and two world wars to do it.