It was early in the morning in Halifax, Nova Scotia on December 6th, 1917 but the burgeoning city’s harbor was already hard at work.

Although far from the front lines of Europe’s global conflict, Halifax had found itself as the tip of the spear of Canada’s involvement in the Great War. Part of the United Kingdom’s economically vital Caribbean-Canada-Britain shipping triangle, the port was the starting point for numerous Atlantic convoys, as the city represented the end of the Intercolonial Railway system of Canada. Raw materials, and raw recruits, boarded transports bound for Western Europe, as the port’s Bedford Basin provided protection against German U-boats prowling off the city’s shores. Despite the proximity to the war, the conflict had been a sizable boon for Halifax, swelling the city’s population and coffers to undreamed-of proportions.

The sound of dueling ship’s whistles that 7:30am was hardly out of the ordinary. The Norwegian freighter the SS Imo and the French cargo ship the SS Mont-Blanc were both in the harbor’s narrows, each telling the other, via their whistles, that they believed they held the right-of-way. A collision was imminent. What only some in the harbor knew was that the Mont-Blanc was laded with TNT, picric acid, highly flammable benzole, and guncotton.

The largest man-made explosion in human history was about to occur – and claim or maim 11,000 civilians in the process.

The remains of Halifax – the largest man-made explosion in history until the nuclear bomb

The explosion would happen against a backdrop of one of the greatest challengers the Entente would face during the entire Great War – overcoming Germany’s unrestricted U-boat campaign.

The resumption of unrestricted submarine attacks had sharply divided Germany, with most of the nation’s civilian leadership staunchly against any campaign that would alienate neutral parties and potentially lead to the entry of the United States into the war on the side of the Entente. But with the British blockade slowly starving Germany, the reward of crippling the British war machine was worth the risk of expanding Germany’s ever-growing list of enemy nations. The gamble seemingly had paid massive dividends in early 1917 – despite the United States choosing war, Germany was sinking an average of over 612,000 tones of Allied shipping, en route to Britain losing 6 million tons of vessels that year alone. The British blockade had now been returned in-kind.

Despite the losses, and the threat to London’s ability to supply her armies scattered across the Empire, the Royal Navy refused to adjust her strategy. Supply ships would continue to sail alone and otherwise unprotected, save perhaps an occasional deck gun or anti-submarine weapon.

The convoy system – it radically reduced Allied shipping losses after significant resistance against the idea

The solution had been staring them in the face, because it had been used against them: a convoy system of merchant ships protected by an outer-ring of warships. Germany had already started their own convoy tactics in 1915 to guard their iron ore shipments from neutral Norway and Sweden. Like the British Royal Navy, the German Imperial Fleet at first balked at the idea that their warships would be assigned a watchdog role over replaceable freighters. But the insistence of the German Baltic Fleet commander, Admiral Prince Heinrich of Prussia, forced the Navy’s hand – Germany’s fleet would organize convoys for their merchant marine. The results would be incredible – from 1916 until the end of the war, Germany lost only 5 freighters to enemy action.

The Royal Navy was unmoved. Practicality, with a small dash of pride, was at the heart of the opposition. The Royal Navy still viewed their principal role as supporting the blockade and providing a check against any renewed German interest in sailing into the Atlantic. Given the damage the blockade was causing within the German economy, diverting ships to convoy duties appeared to be jeopardizing London’s single greatest weapon. The Royal Navy, despite her reputation, simply lacked the vessels to blockade Germany, keep the Imperial Navy in check, and guard supply ships.

By April of 1917, a solution had to be designed. Merchant marine losses would top 860,000 tones that month and Britain’s grain surplus would fall to a six-week supply. If supply ship losses weren’t curbed immediately, Britain would run out of food within months.

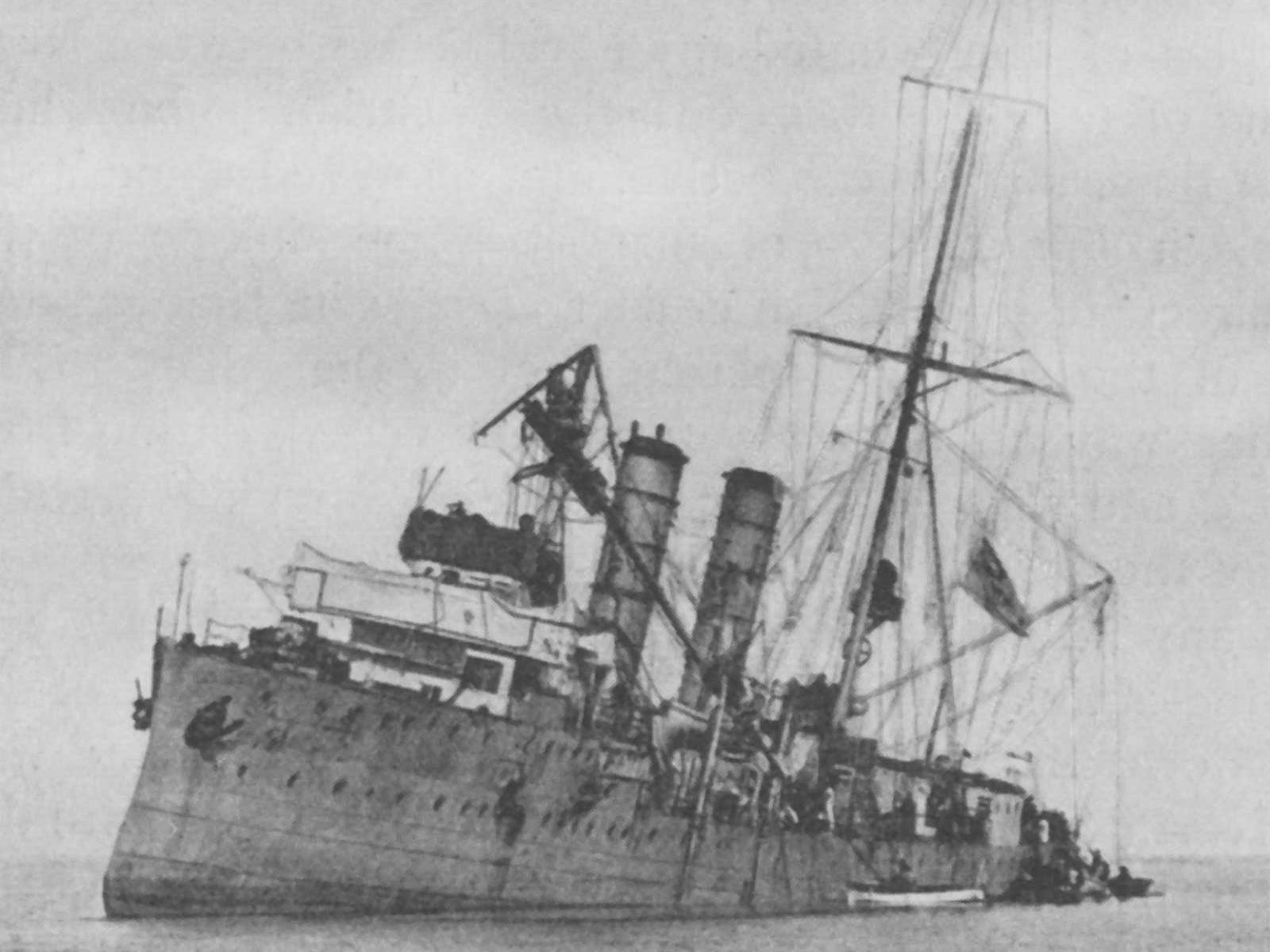

A sinking freighter – at the height of the U-boat campaign, 16 ships a day were being sunk

Makeshift convoys were soon running across the Atlantic, made-up from a loose collection of aging British destroyers and cruisers. But the challenge of providing convoy protection wouldn’t fall to Britain alone – American, French, Brazilian and even Japanese warships would soon escort convoys to English ports.

The Royal Navy had severely overestimated the number of vessels necessary to provide adequate convoy protection, and severely underestimated how quickly the convoy system could affect their shipping losses. Immediately, convoys suffered 10-15% fewer casualties than they had sailing alone just weeks earlier. London had estimated that guarding convoys would require a 1-to-1 ratio of escorts to supply ships, but soon learned that dozens of freighters could be guarded by a handful of destroyers. Aided by some 30 American destroyers assisting in the blockade of Germany right after the American declaration of war, experienced British warship crews were striking back at the U-boat packs.

Technological innovations also assisted in the counter U-boat campaign. While the depth charge had been invented just prior to the war in 1913, the early designs were as much a hazard to the dropping ship as the submarines they targeted. It would be almost two years into the war, in March of 1916, before a depth charge actually sunk a U-boat. Even then, hitting the enemy seemed more like luck than skill as the range of most depth charges was under 100 feet and most ships carried only two. But newer depth charges carried a greater range, 300 feet and over to be lethal to their targets, and could be produced in massive numbers. Whereas in 1916, a ship might have two depth charges and the entire Royal Navy might fire 100-300 a month, by the end of the war, most ships had dozens of the weapon and over 1,700 would be fired on average per month. U-boat losses soared.

A German U-boat sails for cover

Convoys couldn’t prevent all losses. Like sharks, the U-boats now typically picked off only stragglers who couldn’t keep up with the rest of convoy. Bolder U-boat commanders might risk striking at the bulk of the convoy, but having convoy escorts often meant a U-boat might only get off one or two torpedoes before being discovered and driven off with depth charges. U-boat victories still occurred – 400,000 monthly tones were being regularly sunk even in late 1917 – but came at higher and higher prices for the German Navy. The broader numbers speak for themselves. At the height of the U-boat campaigns, Germany was sinking the equivalent of 16 ships a day. Of the thousands of ships that participated within the convoy system, only 257 were sunk during the entire war.

The actual collision between the Imo and Mont-Blanc didn’t cause much damage. Both ships had halted their engines while vainly attempting to turn, causing at worst glancing blows to one another’s hulls. But the relative force of the collision jarred loose cans of benzol within the Mont-Blanc, and as the Imo attempted to reverse and dislodge itself, sparks flew into the liquid, engulfing the Mont-Blanc in flames.

Cloud from the Halifax explosion – it was said the cloud went 11 miles up

The crews of both ships, as well as the experienced sea hands in the port, understood the imminent danger. The Mont-Blanc contained 2,367 tones of picric acid, 62 tones of guncotton, 250 tonnes of TNT and 246 tones of benzol – it was veritable floating bomb. Two towing scows attempted to hose down the spreading fire, and once they determined the blaze was too powerful to be put out, bravely attempted to attach towing cables to the ship in a desperate bid to move the ship away from shore. The crew of the Mont-Blanc had already abandoned ship, yelling at the top of their lungs to the shoreline to evacuate the port. Few heard their pleas.

Instead, the citizens of Halifax had gathered at the shoreline to watch the spectacle. Of those ashore, perhaps only railway dispatcher Vincent Coleman fully understood the gravity of the situation. Coleman’s quick thinking prevented another 300 people from approaching Halifax via the rail line, warning conductors further down the system that “Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.” Minutes after Coleman’s message, the Mont-Blanc turned Halifax into a Holocaust.

In a instant, 400 acres worth of sea and land were vaporized. Temperatures of 9,000-degrees erased large chunks of Halifax in a flash as shock waves could be felt 130 miles away. A tsunami crashed into what remained of the city, flooding the rubble while white-ashes rained down on survivors. In the blink of an eye, 1,600 civilians had been killed by the blast with 9,000 wounded. Another nearly 400 initial survivors would succumb to their wounds. Halifax, for all intents and purposes, had been completely destroyed.

Halifax – days later. The city was blanketed in snow the next day, hampering relief efforts

What was left of Halifax was thrown into panic and confusion. Some had no idea what had occurred in the harbor, believing the explosion was the result of a German plane. Instead of rushing out to aide those they could, soldiers were ordered to their defensive positions to repel a forthcoming German invasion. Civilians panicked as the blast caused the ammunition factory to catch on fire, stoking fears of another massive explosion. Only once the fire had been contained that afternoon did the city get down to the business of trying to rescue the wounded.

Canadian, British and American authorities attempted to rush badly need aid to Halifax – only for the city to be hit with 16 inches of snow the following day. There were few places to house the city’s inhabitants – over 1,600 homes had been destroyed and 12,000 more were damaged. Nearly 25,000 people, roughly a third of the city, were either homeless or otherwise exposed to the elements. Nor did it comfort civilians that the rebuilding efforts centered on getting the port back to operational status first. Despite British fears that Halifax Harbor wouldn’t be usable for months if not years, the first ships sailed out of Halifax merely days after the destruction. The war effort wasn’t going to stop – not even for the largest explosion in history.

The “Halifax Explosion” would become the metric by which the world measured the destructive capabilities of explosives. Hiroshima would be first described as “seven times the Halifax Explosion” as the legacy of the incident only grew during the inter-war years.

The anchor from the Mont-Blanc – part of the Halifax Monument

Less remembered were anti-German and anti-French reactions of the Halifax population following the explosion. Those who insisted the explosion had to be an act of German sabotage had their case temporarily strengthened as John Johansen, the Norwegian helmsman of the Imo, was arrested on charges of being a German spy as a letter, written in German, was found among his possessions. The letter was actually in Norwegian and Johansen was let go.

A far stronger case against the Imo and Johansen was that the ship was sailing on the wrong side of the narrows, meaning the Mont-Blanc had the right of way. But with anti-French sentiment running high in Nova Scotia, a formal inquiry cast blame with the Mont-Blanc‘s captain, Aimé Le Médec, the ship’s pilot, Francis Mackey, and Commander F. Evan Wyatt, the Royal Canadian Navy’s chief examining officer in charge of the harbor. All three would be charged with manslaughter and criminal negligence under the faintest of evidence and fortunately most charges would be dismissed. Only Wyatt would stand trial, albeit in one that lasted less than a day and found him completely innocent of any wrongdoing.

A memorial with the remains of the Mont-Blanc‘s anchor marks the official remembrance of the city’s near complete destruction. The anchor had been found in the recovery efforts – two miles from where the ship exploded.

Amazing. I’d never heard of this before.