We’ve fallen a little behind on our World War I series. Over the next few weeks/months, we’re going to work to get caught-up to the calendar.

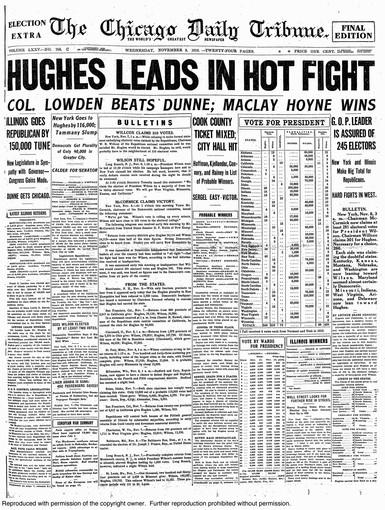

As the night of November 7th, 1916 became the early morning hours of November 8th, supporters of Charles Evans Hughes were becoming increasingly confident.

The former New York Governor, Supreme Court Justice and Republican nominee for President, Hughes had waged a brief campaign – he hadn’t sought the office but accepted the nomination in June – but looked as though he was on the verge of winning. Hughes had all but swept the Eastern states, racking up victories in large electoral college states like New York, Pennsylvania and Illinois. By the time the reported results had turned to the Western states, Hughes already had nearly 249 electoral votes (New Hampshire was still too close to call) out of the 266 he needed to win. The early numbers in the West had favored incumbent President Woodrow Wilson, but Hughes’ camp felt secure that he would obtain at least Oregon and California’s votes. Together, they would deliver the Presidency to Hughes.

Despite Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare and numerous acts of terrorism, America had remained neutral in Europe’s conflict. Wilson had campaigned largely on his ability to keep America out of the war, while Hughes had spent the last five months questioning the nation’s preparations. Despite Hughes wanting to side-step any mention of the war directly, the campaign’s final weeks had devolved into a pro-neutrality versus pro-Entente/pro-war election.

The results from Oregon and California, although not official, arrived early in the morning – Hughes looked likely to win them both. As Hughes drifted off to sleep, it was as the President-elect of the United States. America had taken one step closer to preparing for war.

It’s not quite “Dewey Defeats Truman” but the nation assumed they had narrowly elected Charles Hughes as President

The common historical refrain of America’s attitude about the Great War in 1914 was that the nation staunchly preferred peace. In reality, the nation was strongly divided on a variety of issues surrounding Europe’s conflict.

Distance at first dimmed the reality of the war. The invention of the telegraph and the laying of the Atlantic cable could provide nearly up-to-the-hour reporting on events on either side of the ocean, but it still could be days or more for news to spread beyond the coasts. For the average American, the newspaper stories on the war might as well have described fictional locations – as they involved lands they had never seen and likely never would. And for the nearly 1/3 of the United States that was first or second generation immigrants, the war in Europe represented precisely what they or their parents had worked to escape.

Still, ethnic loyalties lingered. A month after the sinking of the Lusitania, Irish and German protesters mounted a massive peace demonstration in New York City, while there were pro-German/pro-neutrality picnics and rallies throughout the summer in the Midwest. The streets of Chicago erupted in violent clashes between Slavs and Germans. Cincinnati Jews talked of raising a Jewish militia to join the German forces fighting the Tsar.

Wilson hadn’t wanted to focus on the war to start the campaign – fearing it would backfire. But his insistence on keeping America out of the war would ensure his re-election

Every American institution – politics, religion, business – found themselves torn over the war.

Few, if any, prominent political figures openly argued for the United States to intervene in Europe, but the degree of the nation’s neutrality was hotly contested. Former President Theodore Roosevelt had been highly critical of Wilson’s handling of American neutrality in the face of German naval attacks while other Republican Senators like Robert La Follette and George W. Norris backed a strict non-interventionalist policy. The war would divide Wilson’s Cabinet, as Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan would resign following Wilson’s relatively tepid rebuke to the Germans after the Lusitania – deeming it too inflammatory. “Why be so shocked by the drowning of a few people,” Bryan stated, “if there is to be no objection to starving a nation?”

Most American religious institutions were too busy evangelizing for the temperance movement to offer much commentary on the war beyond a “plague on both houses” mantra, but a theological divide still simmered. Catholics, many given their Irish or German roots, had little sympathy for the Entente while many Protestant denominations attempted relief operations for Belgian civilians following the lurid tales of German repression.

Wilson was running for re-election during a major American economic boom – unemployment fell from 9.7% in 1915 to 4.8% in 1916. Hughes’ critiques would center on the nation’s preparedness and the belief that reuniting the pre-1912 GOP coalition would be enough to win

American industry loved neutrality as a policy, but most assuredly chose sides. The nation’s GNP jumped 20% as exports to the Entente increased from $824.8 million before the war to over $2 billion by the beginning of 1917. Many of those exports were being bought on credit as the Allies began to bankrupt themselves J.P. Morgan alone financed a $500 million credit deal with Britain and France – roughly the equivalent of nearly $12 billion today. Still, there those industrialists who decried the entire conflict. Henry Ford attempted to personally sail peace delegates to Europe in 1915 aboard his “Peace Ship” (the press dubbed it the “Ship of Fools”).

For whatever the strengths or weaknesses of neutrality as an official U.S. policy, it was easier than trying to unite a divided people to participate in a conflict they felt had little impact upon them.

For some prominent American leaders, the nation’s policy was naiveté, not neutrality.

Wilson was strongly criticized by all sides for his reaction to the German sinking of the Lusitania. Liberals thought Wilson too hard while conservative thought him too soft

The United States Army consisted of only 98,000 troops in 1914 – and almost half of that number were stationed outside of the U.S. Even with the inclusion of the National Guard, America’s infantry would rank only as the 13th largest in the world; outnumbered 20-to-1 by Germany’s manpower alone. The Army had invested no funds into tactical research of trench warfare, gas weapons, tank or plane development and had nearly had their budget cut in 1915. Only after the Lusitania and the Pancho Villa Expedition did Congress halt their proposal.

For Theodore Roosevelt and U.S. Army Chief of Staff Leonard Wood, America was dangerously unready for a potential war. Partnering with former secretaries of war Elihu Root and Henry Stimson, the group launched what would be known as the “Preparedness Movement.” In practicality, the group was as much political as practical. Roosevelt, Wood, Root and Stimson were all Republicans who agreed on a far more robust foreign policy than being currently proposed by President Wilson. In execution, “Preparedness” was largely a movement in favor of conscription – in this case, a plan to require six-months of military service for all 18 year-olds.

The concept of mandatory military participation was extremely unpopular, and it likely rankled the Movement’s founders that critics unfavorably compared the idea to Germany’s two-year active service law. But “Preparedness” was not deterred, forming a camp at Plattsburgh, New York for military training. The concept was very similar to the recruitment of the “Rough Riders” decades earlier, and for good reason – Roosevelt had been a major proponent of the Rough Riders, with Wood that group’s commanding officer. The Plattsburgh camp was so popular, that similar camps and programs sprung up around the nation. Over 40,000 young men, most of them coming from middle to upper class families, would attend Plattsburgh over the next year.

The Plattsburgh camp – Teddy Roosevelt and Gen. Leonard Wood are on the bottom right

Plattsburgh and “Preparedness” on their own didn’t spur much action from Washington, but the prospective presidential campaigns of Roosevelt, Wood and Root did. Wilson’s immediate response was to attempt to downplay the status of the American military. With Democrats in control of Congress, Wilson’s administration had a series of generals and admirals testify as to the war-readiness of their units. Wilson’s Republican opponents didn’t buy the testimonies and the administration’s insistence that America was fully capable of defending herself came across as worryingly defensive to the public at large.

Unable to sell the public that improvements to the military weren’t necessary, Wilson next proposed a massive military expansion – of the navy. A program to build the U.S. Navy to the size of the British Royal Navy within the next decade was intended to mollify skeptics, but it only reinforced the growing notice that Wilson was ignoring the global state of affairs. Wilson’s supporters viewed him as having sold out the “war lobby” while critics hounded on the notion that the United States should be planning on a strategy that seemed designed to counter Britain, not Germany.

With the conventions of both parties approaching in the summer of 1916, Wilson and the Democratic Congress made one last attempt to cut off the political support for “Preparedness” at it’s knees without alienating the anti-war sentiments of the Democratic Party. The National Defense Act of 1916 provided a significant increase in the size of both the standing army (up to 175,000) and the National Guard (450,000). 375 new aircraft would be produced and the navy was given a 3-year timetable for the introduction of new ships. America’s military would still lag far behind their European counterparts, but rearmament was happening.

Preparedness Parade – the nation’s appetite for being militarily prepared was high enough that Wilson would essentially co-opt it for his campaign

Now all Wilson had to do was win re-election.

Before the Republican Party of 1916 could focus on defeating Woodrow Wilson, they had to attempt to mend their own internal divisions.

The Grand Old Party had badly fractured in 1912 as former President Theodore Roosevelt openly challenged Republican incumbent William Howard Taft, only to split off with the Progressive Party (often known as the “Bull Moose Party” from Roosevelt’s own comments after being shot during the 1912 campaign – “it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose”). With a three-way contest, and Progressive candidates up and down the ballot, Wilson had won and the Democrats gained 61 congressional seats.

Four years later, Roosevelt was bound and determined not to let Wilson return to the White House – even at the expense of his own ego. When the Progressive Party contacted Roosevelt to inform him that he’d been nominated again by them to run for President, TR telegraphed the convention that he would decline the nod. Roosevelt was planning on endorsing the Republican nominee. The telegraph started a veritable stampede out of the door, with many Progressives abandoning the party to rejoin the GOP. As a result, the Progressives wouldn’t field a presidential candidate in 1916 and the party would quickly die on the vine.

The Republican convention in Chicago – Hughes hadn’t run in the primaries but was still nominated

If many liberal Republicans were eager to rejoin the GOP, the Party’s leadership was equally eager to find a candidate they could support. Charles Evans Hughes had spent the last six years out of the electoral limelight as a fairly center-left Supreme Court Justice. Appointed by Taft, Hughes had previously been the Governor of New York and counted Roosevelt as a close supporter. Hughes hadn’t announced or planned for a candidacy and yet won the nomination in three ballots as party leaders pushed him as a compromise candidate.

Hughes would prove to be a cautious campaigner, preferring to let surrogates like Taft and Roosevelt make his salient points. Doing so only put Hughes in a bind. While Roosevelt repeatedly hammered Wilson’s handling of the Lusitania (TR suggested Wilson was letting Germany “bully” the U.S.) and the concept of “Preparedness”, Hughes desperately wanted to bypass the issue of the war, lest he come across as the “pro-war” candidate. It was a difficult proposition; between his handling of German submarine warfare and his seemingly confused Mexican intervention, Wilson was vulnerable on his foreign policy, but generally popular on the most important foreign policy point – he had kept America out of the war.

Hughes and the GOP were nevertheless confident – a Democrat hadn’t won consecutive presidential elections since 1832. Hughes was so confident (or perhaps so cautious), he didn’t meet with California’s Progressive Republican Governor Hiram Johnson. Johnson was a leading anti-war Republican (and Roosevelt’s former 1912 running mate) and was now seeking the Senate. It was better, Hughes rationalized, to not been seen with Johnson close before the election than risk re-opening some party divisions.

Wilson too had issues with how to approach the war. At the Democratic convention, William Jennings Bryan would coin the slogan that Democrats would use throughout the fall – “He Kept Us Out of War.” Wilson disliked the slogan, partially fearing it might make him look too weak and partially sensing how oddly it played as he criss-crossed the nation touting the National Defense Act; essentially his own preparations for war. Still, Wilson hammered Hughes relentlessly as the candidate who would embroil the United States in Europe’s affairs if elected. It was proving to be an effective tactic.

Hughes campaigning in Winona, Minnesota

The issue of the war was also significant with a new voter demographic – women. While the 19th amendment was still four years away, 12 states already allowed women to vote. If the election were to turn on the support of women, it looked as though Charles Hughes would walk away in a landslide. Wilson had been less than supportive of the women’s suffrage movement while Hughes publicly backed them. The “Hughsettes” as they would become know, would include a number of notable suffrage leaders who campaigned for the Republican across the country. Wilson supporters would often riot and attack the “Hughsettes” rallies.

Despite Hughes’ public support, women overwhelmingly voted for Wilson. In the 12 states where women could vote, 11 of them went to Wilson. The Republican might push for granting them the vote, but Wilson would keep them out of the war.

It was the morning of November 8th, 1916 as the telephone rang in Charles Hughes’ residence in New York. A reporter wished to get Hughes’ reaction to the election news from earlier that morning. Not wishing to disturb Hughes’ slumber after such a late evening, Hughes’ butler informed the reporter that “the President is sleeping.” The reporter replied: “When he wakes up, tell him he isn’t the President.”

By the end of the week, the results had flipped – Wilson was re-elected

Oregon had indeed gone for Hughes that night, although not New Hampshire (by 56 votes). But California and it’s critical 13 electoral college votes had gone to Wilson…by 3,800 votes. Wilson would eventually win 277 electoral votes to Hughes’ 254. Hiram Johnson, so incensed by Hughes’ snub, refused to put his political machine to work for the Republican nominee. Perhaps as painful? Women had gone for Wilson by a 3-to-1 vote in California.

It appeared as though the United States had voted to ensure it stayed out of Europe’s blood bath. Within a month of Wilson’s inauguration in March of 1917, America would be at war.

The whole thing reminds me of a joke my dad used to tell. “They told me that if I voted for Barry Goldwater, we’d have a horrible war in Vietnam. Sure enough, I voted for Goldwater, and we had a terrible war in Vietnam.” Not having a good choice in an election seems to be an old problem, though.

Wow! I wonder if that election is where libidiot women started their gullibility?

Of course, Woody Wilson also foisted the Fed on the brain dead minions. He knew it was going to “kill his country”, but he still signed it.

Trump claims to have a “secret plan” to fight ISIL. Well, by analogy to past secret plans, Vietnam’s doing OK these days, so maybe there’s a glimmer of hope…

the election of 2020 will mirror the election of 1912 with parties being reversed, Bernie Sanders will be on one side no one knows who will be on the other.

Joe Biden isn’t young enough to run anymore, and Joe Biden is too old and white for most Democrats anyway. The Democrats will seek to enhance their appeal to the new swing voters, middle-income conservatives embarrassed to be in the party of Trump.

Wilson had been less than supportive of the women’s suffrage movement while Hughes publicly backed them. The “Hughsettes” as they would become know, would include a number of notable suffrage leaders who campaigned for the Republican across the country. Wilson supporters would often riot and attack the “Hughsettes” rallies.

Wow, things have not changed much in the last 100 years! Just the historical narrative being pushed by libturd progressive media that Dems are all-inclusive and womyn-friendly.

Sigh… 3800 votes from League of Nations not being created.

I only now discovered Shot in the Dark, or maybe rediscovered it again. Something about mostly nekid girls protesting something with some wearing only electrical tape on top. A red head saved the photo. They often do.

As there is a WWI and WWII feature here I thought I would mention a local Military History Book Club, meeting usually the 4th Wednesday of the month at 7 PM at the Roseville Har Mar Barnes and Noble. You don’t have to read the book to show up.

So the next one is 7 PM Wed Jan. 25th, 2017. The book (a longer book over the long Christmas break) is Guns at Last Light, by Rick Atkinson, about WWII from D-Day until German surrender. The Feb. 22nd book is Hitlerland: American Eyewitnesses to the Nazi Rise to Power by Andrew Nagorski.

Joe Biden isn’t young enough to run anymore, and Joe Biden is too old and white for most Democrats anyway. The Democrats will seek to enhance their appeal to the new swing voters, middle-income conservatives embarrassed to be in the party of Trump.

EI,that’s a joke right? There is no rush to the center I see. If the trends continue we will have a filibuster proof majority in both houses for Trumps 2nd term. What make you think the Democrats have any sense to win back the white working class? Especially since union are about to realign politics in something not seen in 50 years

Eclectic,

I have a conflict tomorrow night, but I’d love to come to the February event.

Thanks!

PoD: If you mean the next mid-terms, Trump will not be up for election, the House has a built-in Republican advantage thanks to Republican-controlled state legislator gerrymandering, (which Republicans earned their re-districting rights through their dominance of state politics) and the Senate election will see many more Democrat seats than Republican seats to defend. We could quite easily see 4 years of complete Republican control.

Sigh… 3800 votes from League of Nations not being created.

3800 votes from a decidedly different U.S. approach to the war and the Versailles treaty. Perhaps a more pro-war U.S. would have modified the terms and avoided World War Two? Never know, but interesting to contemplate.

EI: I just meant in regards to the fact the party is literally entering unelectable territory

Eclectic,

I will definitely be there one of these days. I’d have a heck of a time getting over there anytime soon, anyway I could Skype in? I’m a massive history nerd

PoD: The Democrats, once the cutting edge of progressive politics, has been brought to the edge of extinction, in part, because of its obsessive fantasies about Identity Groups rather than economic classes.

Pingback: The Yanks Are Coming | Shot in the Dark