It was well before dawn, on what promised to be a warm day in central France.

The 11th Battalion of the East Lancashire Regiment – the “Accrington Pals”, who’d volunteered en masse for service in the war, in line with the great British tradition of turning out for King and Country – had had a busy year; after a stretch of duty guarding the Suez Canal in Egypt, they’d been recalled to France (along with their 94th Infantry Brigade, part of the 31st Infantry Division, a unit of about 15,000 men recruited in the north of England in the first autumn of the war.

The 11th Battalion of the East Lancashire Regiment – the “Accrington Pals” – parading in Accrington in 1915.

Like the rest of the Brigade, they’d seen little to no action – Egypt worried the Imperial General Staff greatly, but the Ottoman Turks had never managed to make good on the potential threat they posed; indeed, they’d largely crumbled throughout the Middle East – partly as a result of post-dated self-determination checks written by the British and French that we’re still paying for today, especially in “Palestine”.

But as the war dragged on into its third bloody summer, the Accrington Pals became part of the General Staff’s plan to make a major difference in the war.

And they did – but not in the way that the Staff planned.

Butcher’s Bills: The enduring impression of World War I is that of endless rows of trenches, which were the catalyst for the greatest concentration of bloodletting in history.

The impression is both accurate and misleading.

The common perception is that World War I’s bloodiest days involved lines of infantry swarming across “no mans land” – the land between the opposing rows of trenches – and getting mowed down in droves by machine guns, poison gas and artillery. And there is some truth to that; battles like First Marne, First and Second Ypres, the Loos, Neuve Chapelle and Verdun were cultural metaphors for “bloody futility” in European culture while the World War I generation was still alive; to some extent they still are.

But the bloodiest single day in World War I was among its first days, when the great armies still maneuvered about in the open, and cavalry still roamed Belgium and northern France.

French infantry, 1914. The cloth caps and shoulder-to-shoulder lines would be replaced by helmets and tactical dispersion within the year.

The Battle of Lorraine, 22 August 1914, saw the deaths of 27,000 French troops (twice as many were wounded), and probably half as many Germans, as the French, maneuvering about with tactics little changed since the Napoleonic wars, ran into dug-in German infantry, modern breech-loading artillery, and the Maxim machine gun. The opening months of the war saw over 300,000 French casualties, and about as many Germans. The British – benefitting from their experience in the Boer War, which taught them that advancing across fields in long rows was suicidal against dug-in-men with modern rifles, suffered relatively less, but their 29,000 casualties broke back of the elite British Expeditionary Force anyway. A shocking percentage of the dead were lost to modern artillery and machine guns.

And so the armies dug in, and spent the next two autumns, winters and springs shelling, raiding, gassing, and occasionally attacking, each other in a bloody war of attrition.

British infantry waiting to move forward from a communications trench – a trench leading to the front lines.

Both sides adapted to the new conditions; since their targets were no longer obligingly above ground, artillery started using fuses to try to detonate above the trenches, raining shrapnel down; in turn, the men below started living in dugouts underground until there were signs of impending attack. When they came up? The massive number of head wounds and what we today call “traumatic brain injuries” caused by the shrapnel led to the invention of the steel helmet, replacing the cloth caps and leather “Pickelhäube” of the early days of the war, and still used (in newer, lighter Kevlar form) today.

A French infantryman’s helmet – the first issued to foot soldiers since the days of pikes and swords; shrapnel killed 2-3 men in World War 1 for every man killed by rifle or bayonet fire.

Trenches evolved, from long, simple ditches to elaborate excavations, with firing steps next to deeper areas for movement back and forth, and dugouts for sheltering all but the lookouts under artillery fire; machine guns sat in fortified strongpoints. Both sides kept each others heads down, and kept each other on edge; snipers scanned no mans land, looking for scouts, enemy inexperienced or rash enough to show themselves, and of course each other.

A German sniper and his spotter scan No Man’s Land.

Raiding parties probed enemy defenses and outposts, keeping the other side on edge and nabbing the occasional prisoner for intelligence purposes. The “trench mortar” – a simple tube for launching a small grenade powered by a shotgun-shell-like charge in a high arc into an enemy trench, became an essential infantryman’s tool, which it remains today. Between the sniping, the raiding and the constant threat of explosives dropping out of nowhere, life in the front line of trenches was as exhausting as it was hazardous and, paradoxically, tedious.

The armies learned to stop crowding everyone into the front row of trenches; the front line was held by about a third of a unit’s strength; the other two thirds would be held several hundred yards back, under cover in dugouts and bunkers, resting (relatively speaking) and ready to move to the front.

A stylized cross section of a section of trench.

As defenses evolved, so did tactics for trying to overcome them. The long, elbow-to-elbow lines of infantry that got torn to pieces at the Battle of Lorraine were replaced by groups of men advancing on a narrow front, but in depth; a brigade of 3,000 men might advance across No Man’s Land on a front 160 men wide, but several waves deep; the men took up different tasks in the assault; some carrying and throwing grenades to take out strongpoints, some with rifles, others with light machine guns to provide covering fire to get the grenadiers up close, and others; above all, the infantry learned to advance behind a wall of covering artillery fire. When it went well – when the infantry advance and the artillery fire was properly coordinated (in the days long before radio could be carried on a man’s back, which meant all coordination took place in meetings hours or days before the battle), the infantry would be arrive at the enemy’s front line of trenches moments after the artillery lifted, as they were coming out of their dugouts and getting organized. When it didn’t work well, the artillery line would advance faster than the infantry could (or mud, barbed wire and inexperience would slow the infantry down), giving the enemy plenty of time to come up and get organized.

Stacks of empty artillery shell casings – the relics of a days-long artillery barrage.

At Neuve Chapelle, it worked; British and Indian troops overwhelmed a few lines of German trenches and took, by World War I standards, a fair chunk of ground (while failing to achieve the most treasured goal, a breakthrough past the trenches). When it didn’t work? It led to epic fiascoes and piles of dead.

And so the two armies sniped, raided, bombarded, bombed and blasted each other for months on end, taking a steady, constant toll of lives, interrupted by occasional offensives that killed thousands, sometimes erupting into extended, bloody slogging matches like Verdun.

Home By One Of These Christmases: The optimism of the first fall of the war – when both sides believed they’d be home and done by Christmas, the war wars had been fought before Napoleon – came to grief in the first winter of the war – but the desire to end the war and its endless, hideously expensive butchery was always there.

French and British generals gather at the Chantilly conference to plot strategy, December 1915. Their plans were completely upended by German actions mere weeks later.

In late 1915, after the bloody debacles of the spring and summer, the British and French staffs gathered at Chantilly to plan an offensive that would break through the German line, exploit the lack of German reserves (lost in the meatgrinder at Verdun, or transferred to the sprawling, mobile war against the immense Russian army in the east) for a big push that, they hoped, would be a decisive blow to lead to a final decision.

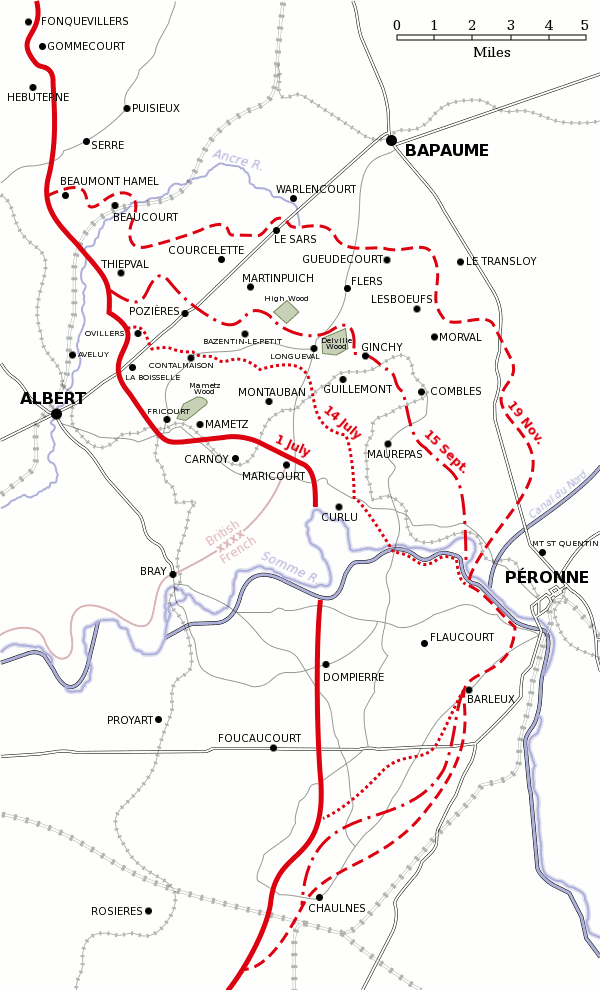

The original plans called for a maximum-force push by a combined British and French force on both sides of the Somme river, in central France.

The attack would incorporate:

- The lessons both the French and British had learned about trench warfare – including lessons on how to advance on enemy trenches without getting slaughtered

- Massive, smothering force; an overwhelming attacking force, advancing behind the greatest artillery bombardment in history – itself learned from the lessons of 1915, when British artillery was chronically short of ammunition.

- A six day long artillery bombardment, intended to crack the sanity of any German troops that weren’t killed.

- At the end of the long bombardment would be a five minute “Hurricane” of explosives and steel, followed by a “walking bombardment” – a curtain of explosions moving forward at a walking pace, with the infantry advancing so close behind that some casualties were to be expectied.

- Kitchener’s fresh “New Model Army”, bolstering the remains of the “Old Contemptibles” and “Territorials” from the first year of the war.

No plan ever survives its first contact with the enemy – and in the case of the Somme offensive, it didn’t even survive the previous battle. The German offensive at Verdun, launched a week after the planning for the Somme started, and the hideous toll in casualties that resulted, forced the French to divert about half of the troops intended for the Somme, turning it into a largely British effort. The German Verdun offensive was itself thrown off kilter by the Russians’ Brusilov Offensive, causing them to shift their own reserves to the East.

And so the plans ambitions were scaled back; from an attempt to break through and clear the Belgian coast of U-boats and, possibly, exhaust the Germans, to a limited offensive to draw pressure from Verdun.

It was still a huge offensive; 20 British and 13 French divisions. The French – the hard core of the vast draftee army that had taken the field in 1914 and survived the slaughter in Lorraine and other bloodbaths early on, were highly experienced in fighting among the Trenches.

The British, though, were another matter.

The Price of Success: The British Expeditionary Force of 1914 – six infantry and one cavalry divisions – had been bled white – but had been replaced several times over by Kitchener’s New Armies. In the 20 months since the war began, the British Army in France had grown from those first seven, utterly elite, divisions, to sixty divisions; surivivors from the Contemptibles, troops from all over the Empire (Canadians, Australians, Rhodesians, Indians, New Zealanders, and even a battalion from Newfoundland, which was flirting with independence at the time), and of course, the vast levies of volunteers, including the dozens of “Pals Battalions”.

Increasing an army tenfold in under two years is a daunting job; doing it under fire, while your junior leadership and NCO corps is taking heavy losses, without some loss in leadership, professionalism and quality, is almost impossible.

And so the British Army that was lining up in the trenches on the morning of July 1 was a very different force than the one that had faced the Germans in September of 1914. In particular, most of the “Pals” were seeing combat for the first time. More crucially, their leaders – especially the company commanders, platoon leaders, and non-commissioned squad leaders and platoon NCOs – had never tried to lead men under fire before.

Three Battles: The Somme has been for the past 100 years as much a cultural metaphor as historical event. All of the legendary bloodbaths of World War I are fading a bit in cultural consciousness as the very last of the World War I generation first left political prominence (the last American presidents who served during the war, Truman and Eisenhower, left office in the fifties), then social prominence, and finally died altogether.

A Lancashire Fusilier near La Boisselle, in a captured German trench, with his light machine gun. German counterattacks south of the Albert/Baupaume road were slaughtered with severe casualties.

The metaphor? Futile, soul-crushing, waste of life. The Somme stayed in the British conscience for the better part of three generations as the tragic result of getting too involved with the affairs of the Continent, and a symbol of the utter futility of war. That conscience became aware at a cultural level of the immense wasteage of talent, energy, brains and brawn, on those muddy, shell-scarred fields.

But as World War I battles went, it was a very mixed bag. And those bags mixed at three points:

- South of the Somme River, which was the “switch line” between the British and French armies. This ten mile front was the responsibility of the French Sixth Army.

- From the Somme to the Albert/Baupaume road – the southern part of the British Fourth Army.

- North of the road, to roughly Gommecourt, around which was the northern boundary of the offensive, with the rest of the Fourth and elements of the British Third Army.

A British unit after capturing the village of La Boisselle – just south of the Albert-Baupaume road, with captured German equipment. Mere yards to their north, nobody was smiling and nobody had captured anything.

And within the context of World War I trench warfare, the three sectors could hardly have been different.

South of the Somme (and, with one French division on the north bank, south of Maricourt), the French Sixth Army – highly experienced in fighting in the trenches – filtered into No Man’s Land in small assault parties under intense artillery cover, descending on the German trenches in a nearly perfectly-coordinated assault. The Germans north of the river withdrew under heavy pressure – and south of the river, the German lines were so bloodied that their commander judged them incapable of resisting the second French wave. The French met all their first day objectives with relative ease; the operative word being “relative”; the French suffered 7,000 casualties on the first day at the Somme; a ghastly toll to modern sensibilities, but blessedly light by the standards of the day. It was considered an unfettered success, given the limited scope of the attack plan; their casualties forced the Germans to attenuate their offensive at Verdun.

A German trench, after the battle.

Between Maricourt and the Albert/Baupaume road, the British fared relatively well, at least on the first day. The British troops were able to follow close behind the bombardment, which did in fact shatter the front line German positions. The terrain between the British jumping-off points (several hundred yards behind the British front lines) and across No Man’s Land to the German lines neither critically obstructed the British advance nor gave the Germans any special advantage. British troops were able to meet their first day’s objectives, and force German withdrawals.

But North of the Albert-Baupaume road, a tragic legend unfolded.

The Tipping Point: The bulk of the British Fourth Army stepped off before dawn, heading east-northeast, first through the fields behind the British front line, and then to No Man’s Land.

But the terrain north of the road was different; the troops had a longer approach to the British front line, and a wider no-man’s land. Both of which could have been dealth with, with careful planning and determined leadership.

But the troops north of the road were largely Pals Battalions, and other, older units whose junior leadership was inexperienced, as the junior officers that had survived the previous 21 months were replaced by new ones straight out of schools, or promoted up from the ranks, frequently with no experience.

Many had served elsewhere until deployed to the Somme; the Accrington Pals, and the whole 31st Division, had been in Egypt, and had fired scarcely a shot in the war; worse, they’d had no practice in carrying out their mission whilst being shot at.

And so they lagged behind the barrage (and in some cases completely botched coordinating with the artillery at all. And the Germans, unlike the low-lying trenches south of the Albert/Baupaume road, had trenches on higher ground. dug deep into chalky soil that was ideal for digging shelters and tunnels (and mines full of explosives – the Brits detonated several such mines under German lines, with widely-varying results).

And the Pals advanced on a wide front, at a walk, carrying heavy packs of ammunition, equipment and grenades; running from cover to cover may have been an option, but on the long, exposed trek to their own lines and across No Man’s Land, most weren’t.

Between the leadership failings, the inexperience, the terrain, the bad timing and bad luck, the Germans were able to take their positions long before the British attack reached their lines.

And it was a massacre. German artillery and machine guns and rows of infantry smashed the advance cold.

Four Liverpool Pals; three living, and one very much not.

The British Army has had bad days, days where thousands died; Agincourt, Waterloo, Rourke’s Drift, Spion Kop, and others. And they had bad days afterwards; Third Ypres, Tobruk, Singapore, and many more.

And as noted above, there were worse days in World War I than the first day on the Somme.

But on no single day in history have as many British soldiers die as on July 1, 1916. 19,240 British and Commonwealth oldiers died; a total of 57,470 were killed or wounded. And for that loss, the the Brits gained…

…virtually nothing. Along much of the front, the British didn’t even reach the German front line. In other sections, small parties of British troops struggled to the German front trenches in squads of a dozen or a few, and seized trenches in brutal hand to hand combat with bayonet and pistols and shovels, only to get swallowed up as fresh German reinforcements responded.

Against nearly 60,000 dead and wounded, the Germans lost a total of 8,000 casualties all told, plus 4,200 prisoners – most of them south of the Albert/Baupaume road.

In one day.

And then came another day, and another, and in the end the Battle of the Somme dragged on until mid-November, swallowing up 480,000 total British, 250,000 French, and nearly half a million German casualties, about 1/4 of them dead before the battle sputtered to a halt with winter’s onset.

But the shock of that first day had an effect far beyond the muddly, blasted fields of France.

It could be fairly said that Britain’s desire to be an empire died at the Somme, as an entire generation of British men became war-weary virtually overnight.

Other nations foundered that day as well. The Canadian province of Newfoundland – which was a semi-independent nation of its own at the time, with political and social traditions very distinct from both the Old World and Canada, sent about 5% of its entire population – 5,000 men out of a quarter million – to war in France or on the Atlantic. On the morning of July 1, the Royal Newfoundland Regiment – the island’s main ground force – went over the top. Of 753 men who’d set out on that morning, only 68 men answered roll-call 24 hours later. A quarter of Newfoundland’s young male population died in the war, most of them at the Somme – an event that gutted Newfoundland’s desire to be an independent nation; they folded themselves into Canada not long after.

To this day – literally, today – while July 1, Canada’s independence day is considered a celebration in most of Canada, it’s a day of mourning in Newfoundland.

Fields Of Fire: The Accrington Pals stepped off toward the village of Serre; they were serving as the left flank of the Fourth Army. They stepped across the wide fields of No-Man’s Land…

…and, largely, disappeared into a hurricane of flame and flying steel. About 700 of the Accrington Pals set out from the point of departure; roughly 235 were killed and 350 were wounded – in about half an hour. The few men that reached the German lines near Serre were killed or captured no more than an hour or two after they launched the attack.

Of the 1,000 men who’d joined the 11th East Lancs 21 months earlier, barely 100 were walking by 10AM, 100 years ago today. An entire generation of young men from East Lancashire was gutted in far less time than I’ve taken to write about it.

And the battle went on.

More to come.

Pingback: Here Be Dragons | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: The Kaiser’s Battle: Part One | Shot in the Dark