The letter that sat on the desk of Britain’s Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, had been eagerly awaited.

Addressed from France’s Ambassador to Britain, Paul Cambon, the contents of the letter were the result of nearly five months of negotiations between Britain and France to reshape the Middle East after the hoped-for fall of the Ottoman Empire. Despite the failings of the Entente to make progress on the battlefield, diplomats Sir Mark Sykes of England and François Georges-Picot of France had sought out success at the negotiating table, slicing and dicing Turkish lands.

What would become known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement would first unite, and then embarrass the Entente, while setting the foundation for the next 100 years of engagement between the Middle East and the West.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement – the final map of the Middle East after World War I wouldn’t be much different

100 years earlier, Europe had seemingly settled most of the map of the world with the post-Napoleonic Congress of Vienna. The result had ultimately satisfied no one, with most of the attendees echoing the parting words of Britain’s Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, who regarded the final treaty as little more than “a piece of sublime mysticism and nonsense.” For Stewart’s heirs across the various powers, the Great War seemed a grand opportunity to re-draft the map of the world for another century.

From the war’s first shots, both the Entente and Central Powers had cast their eyes onto their rival’s territories with hopes of expansion. Whether it was the British and French trying to digest German African colonies, or the Ottomans seeking to expand their Empire to Persia, millions were dying or being maimed for the right to claim sections of the globe most the warring power’s citizens didn’t even know existed.

British foreign policy in the Middle East had long been to prop up the Ottomans against the Russians

Outside of Constantinople or a few holy cities in Palestine, the same could said of the Ottoman Empire’s holdings in the Middle East. But unlike other far-flung territories, the disposition of Ottoman lands had been a subject of discussion for decades.

Russia had held interest in access to western naval ports since Peter the Great had reoriented Russia’s focus to Europe, and following the Empire’s defeat by Japan in 1905, Tsar Nicholas II had begun to look towards the Mediterranean – specifically Constantinople – as Russia’s future Western port. Britain likewise had strong interests in the region, namely ensuring their access to oil for their fleet while preventing Russia from achieving their westward expansion. Even France had previously intervened in the region, having upheld their role as protectors of Christians within the Ottoman Empire (part of the conditions of the normalization of French and Ottoman relations in 1523) as recently as 1860 in what is now modern Lebanon.

The three major Entente powers had patiently watched for decades for any sign that the “sick man of Europe” was about to die. They no longer were willing to wait.

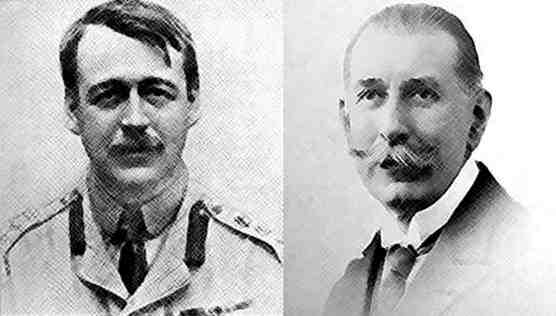

Sykes (left) and Picot (right). Neither probably had the slightest idea what impact they’d have 100 years later

Mark Sykes had been so obsessed with the fate of the Ottoman Empire (the “Eastern Question” as politicians referred to the dilemma), that around London the MP had acquired the nickname “the Mad Mullah.” Viewed as a Lord Kitchener protégé, the Tory backbencher held little political currency in Britain’s wartime government outside of being a vocal supporter of the Arab Bureau – London’s strategic office focusing on Middle Eastern affairs. A disposable political figure, Sykes was an easy choice to enter into negotiations with France over the fate of the Middle East – as a zealous self-proclaimed Middle East “expert”, Sykes would surely fight hard for the Crown’s rights in the region. If negotiations failed, “the Mad Mullah” could easily be thrown under the bus with the excuse that he hardly represented the public stated policies of H.H. Asquith’s government.

Sykes’ French counterpart, François Georges-Picot, was similarly singularly focused on Middle Eastern politics. A member of the French Colonial Party – a loose assortment of prominent French business leaders and officials who pushed for French colonial expansion – Picot had been diplomatically stationed in Beirut before the war. Picot dreamed of a colonial mandate for Syria and Lebanon, albeit with borders far more expansive than either nation’s modern boundaries. A French Syria, in Picot’s mind, stretched from Turkey to the Sinai and from Mosul to the Mediterranean – in essence, almost the entirety of modern Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian territories, plus a large chunk of modern Iraq.

The Entente had placed two low-level officials, both of whom zealously desired the same territories, in charge of resolving a sensitive diplomatic issue with long-lasting imperial consequences.

The image is from Britain’s conquest of Egypt, but the principle remains similar – Britain would horde the spoils of war for herself, and keep the other “predators” (other nations) at bay

The first round of negotiations in London on November 23rd, 1915 led nowhere. The British delegation, led at the time by Sir Arthur Nicolson, the Permanent Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs, were confident that events on the ground would allow the Crown to dictate the terms of the Ottoman Empire’s division. With both Britain and France acquiescing in principle to Russia’s future occupation of Constantinople and the Bosphorus, and British troops about to take Baghdad, there appeared to be little left to debate.

By the time the delegations returned on December 21st, the circumstances had radically changed. Not only were Russian troops still advancing in Anatolia, expanding the Tsar’s eventual claims, but an entire British army had been surrounded at Kut; far short of the goal of Baghdad. With the French emboldened to press their ally at the negotiating table, Sir Edward Grey was prepared to swap out his undersecretary for a wildcard – Mark Sykes.

Sykes’ promotion represented a major diplomatic victory for the Arab Bureau and their pan-Arabic, post-Ottoman, vision for the Middle East. For years, the Bureau had attempted to foster anti-German, anti-Ottoman sentiments by encouraging a pan-Arab sense of nationalism. Such efforts were about to pay off with the forthcoming Arab Revolt of Sherif Hussein bin Ali in June of 1916.

Only a month after the Sykes-Picot Agreement was formalized, the Arab Revolt began – in large part due to British promises of independence

But for other diplomats in London, the Bureau’s views on “Arabia” were in stark contrast to traditional British imperialism – conquest by collaboration with regional leaders. Such means had already been used to great effect in the region, as with allowing the Emir of Kuwait, nominally a qaimmaqams or Ottoman provincial sub-governor, to declare independence while seeking protection from the British Empire. In essence, Britain had been pursing two different Middle Eastern strategies at once – encouraging Arab independence while co-opting Arab provincial leaders under British influence. It was less a case of duplicity than diplomatic and political rivalry, and with Mark Sykes’ promotion to leading the British delegation, it looked as if a winning side had been chosen.

If the Arab Bureau and their supporters had thought Sykes would press hard for their pan-Arabic views, they would be sadly mistaken. Despite his image as hardliner, Sykes’ priority was reaching an accord with the French, and François Georges-Picot was most certainly no “Arabist.” Picot scoffed at the concept that the various tribes under Ottoman rule would be capable of self-governance, let alone motivated by a vision of the region in which a non-Ottoman, more Western-aligned Caliphate would rule over a confederation of independent or autonomous Arab states. Sykes may have been an “Arabist”, but he was also a Francophile. Partially charmed and partially bullied by Picot, Sykes quickly abandoned most of his pan-Arab ideals in order to get an agreement signed.

Sykes was roundly condemned by his Arab Bureau allies, but not only for abandoning their cause. As the negotiations proceeded, the Arab Bureau discovered their Middle Eastern “expert” knew little of the region. T.E. Lawrence called Sykes the “imaginative advocate of unconvincing world movements … a bundle of prejudices, intuitions, half-sciences. His ideas were of the outside; and he lacked patience to test his materials before choosing the style of building … He would sketch out in a few dashes a new world, all out of scale, but vivid as a vision of some sides of the thing we hoped.”

T.E. Lawrence – a semi-prominent figure at this point in the Arab Bureau, Lawrence pushed for greater Arab independence. He did not full believe in self-rule, unlike his film counterpart

Despite the promises of his appointment, Sykes conformed far closer to Sir Edward Grey’s own views on the region. “This Arab question is quicksand,” Grey dryly noted, while Nicolson condemned the Arab Bureau’s pan-Arabism by questioning the very premise. “People talk of the Arabs as if they were some cohesive body, well armed and equipped,” Nicolson insisted, “instead of a heap of scattered tribes with no cohesion and no organization.”

Such dismissive attitudes would literally shape the outcome of the negotiations.

In the minds of the Sykes-Picot negotiators, the various ethnic and religious factions that made up the Middle East had been given strong considerations when drawing out the post-war region. In reality, the Sykes-Picot maps had more to do with consolidating post-war centers of influence.

A painting of the French occupation of Lebanon in 1860. Much of the Christian population in what is modern Syria was forced out

Lebanon was envisioned as a Christian-majority nation, and thus under France’s rule as the traditional defender of Christian rights in the Ottoman Empire. The map largely disregarded the Druze population, which had fought off a Christian uprising in 1860 and resulted in 380 Christian villages and 560 churches destroyed, along with over 20,000 Christian civilians. Picot should have known better – France had led a 12,000-man international force to quell the violence. The Sunni militiamen who had supported the Druze could chose to relocate to the new Sunni-majority nation to the north – Syria, also to be under French control as a colonial mandate.

Shia Muslisms in the region could relocate to the Bekaa Valley, or perhaps further south in what would become Transjordan, and a British protectorate. Or they could significantly uproot themselves and try to move to the southern provinces of Mesopotamia and what would become Iraq.

Palestine would become a vaguely defined “international zone.” None of the Entente seemingly wanted to govern the region, with even proposals floated at the negotiations that Belgium take over (the Belgians were no where a part of the discussion). Sykes himself even suggested granting Palestine to the French. All the parties concerned could only agree on two things – 1) it would be far better to have a European-styled government in Palestine to minimize conflicts with the local Muslims (“By excluding Hebron and the East of the Jordan there is less to discuss with the Moslems…who never cross the river except on business,” wrote Sykes), and 2) no Western power wanted to rule such an impoverished region.

The Balfour Declaration, acknowledging Britain’s interest in Jewish influence in Palestine, would not arrive for another year

One faction that did seem interested in Palestine were European Jews. William Reginald Hall, British Director of Naval Intelligence, noted that “the Jews have a strong material, and a very strong political, interest in the future of the country.” Meanwhile, several prominent Jewish British civilians had begun to pressure Sir Edward Grey for Palestine’s Jews to have a larger role in Palestine’s post-Ottoman government. A Jewish State in the region would minimize direct European rule and safeguard the rights of Christian pilgrims – a goal that the lobbyists from the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland noted with great effect.

The concept wasn’t all that unique. In the early 1900s, there had been a push to grant a portion of British East Africa (modern Uganda) as a Jewish homeland and safehaven from European antisemitism. But with Palestine’s Jewish population under 8%, there was at best only cautious interest in turning the Holy Land over to Jewish settlers. Still, promises were made to European Zionists of future Jewish interests in the region while the Entente attempted to sooth Palestinian Arab fears of European – or even Jewish – rule.

If Palestine’s future was ill-defined, it looked downright concrete compared to the future of “Arabia” in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Neither the British or the French wanted the region, and with vague promises of independence to the Bedouin tribes in the Hejaz region of modern Saudi Arabia, “Arabia” was left to be an autonomous or independent confederation of Arab States – all clearly without the consent or knowledge of the soon-to-be rebelling tribes.

Faisal of Mecca – the son of Sherif Hussein bin Ali, would become the King of Syria and then Iraq following the war. T.E. Lawrence stands over his shoulder to the right

The negotiators knew they had made multiple promises to multiple powers. As long as the tactic remained hidden, perhaps the Entente could wait out the end of the war before dealing with the diplomatic mess they had already made.

The ink on the Agreement had barely dried before private regrets over the document began to surface.

Sykes lamented that he had given up too much to Picot in the interests of striking a quick deal. The rest of the Entente was frustrated that the spoils of war had already been divided. And all the participants acknowledged that too many elements had been left ill-defined.

ISIL propaganda figures heavily on the theme that joining the group helps “break” the Sykes-Picot Agreement

By the time the Sykes-Picot Agreement came to public light, the circumstances of the Great War had radically changed. The fall of the Russian Provisional Government in November of 1917 had already invalidated Russia’s Ottoman claims. The victorious Bolsheviks, eager to embarrass the Entente, released thousands of secret documents – including Sykes-Picot. For a conflict that, by 1917, had become one over the rights of self-determination, due in part to the entrance of the United States, the 1916 agreement to divide the Ottoman Empire for imperial gains appeared horrifically out of date. Desperate to uphold the principles of self-determination, in 1918 the British and French declared their support for “indigenous Governments and administrations in Syria and Mesopotamia.” An international mandate system set up by the League of Nations would govern the formerly Ottoman territories and superseded the Agreement – even though the outlines of the mandates would coincided almost perfectly with those set out in Sykes-Picot.

As the following decades revealed the relative ignorance of those negotiators who drew up the Agreement, Sykes-Picot soon became a short-hand descriptor for European meddling in Middle Eastern affairs. From Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser to ISIL’s Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the goal of “overturning” or “altering” Sykes-Picot has been used as a springboard for pan-Arabic or Islamic hatred towards the West. And as borders of Syria and Iraq dissipate, the amorphous goal of ending the ramifications of Sykes-Picot look closer to reality than ever before.

The Ottomans regarded land as a source of rent, and the people of that land as those who worked the land to produce that rent. That was a normal imperial mindset. The British and French colonial occupiers had essentially the same mindset. When they left, they were replaced by a post-colonial elite whose first impulse was to emulate the colonialists who educated them, aided by foreign industrial interests who were prepared to bankroll elites willing to maintain order and facilitate exploitation of resources. The oil in the region made it a target of cold war interest, which further bankrolled elites willing to maintain order and crush dissent. But the elites and the outsiders sought only order, not a productive people. They paid to prevent disorder, not to improve, educate, and enlighten.

And so now, with the supply of oil exceeding the demand, quite likely for some time, the money to maintain order through despotism is no longer there, and the (much larger) population seethes with dissatisfaction, together with centuries of unresolved grudges. The outsiders are no longer willing to bankroll order, particularly when the cost of order keeps going up. The chaos which might have occurred in 1918, in a much more sparsely populated Middle East, is occurring now. Will peace be made and governments prepared to invest in the productivity and prosperity of their people emerge? Likely not, until much more violence transpires. The 30 Years War is the best analogy, I fear. And Muslim extremism, just like Christian extremism in the 1600s, will continue as long as tribe and sect matter more than brains and productivity.

Pingback: The Arab Revolt | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: The Seventh Seal | Shot in the Dark