Despite the vast expanse of the North Sea, on the afternoon of May 31st, 1916, British Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty had found his prey.

Commanding a squadron of six battlecruisers and four battleships, Beatty’s small fleet had encountered a German fleet of five warships. Both small contingents had spent most of the last two days seeking each other out. Now finally confronting one another, the battle was relatively short as the Germans quickly took out two of Beatty’s battlecruisers. With dry British wit, Beatty remarked “there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.” Withdrawing from the battle, Beatty hoped to encourage the Germans to chase him. The Germans obliged, unwittingly following Beatty into a British trap where a large portion of the world’s foremost navy lay in wait.

As the small German fleet appeared on the horizon, with the early evening sun back-lighting the German ships, only then did the British realize both sides had intended to set a trap on this day – the pursuing German vessels numbered nearly 100, not single digits. Instead of a minor naval battle, both Germany and Britain had committed the majority of their surface forces to a battle that could decide the question of naval supremacy, and with it, potentially the outcome of the Great War.

Off the coast of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula, 250 warships would spend the next several hours engaging in the largest naval battle in human history.*

Jutland wouldn’t be the only clash of surface ships in the Great War, but it would be the most significant by far

The seeds of Jutland had been planted nearly 20 years earlier, thousands of miles away from Jutland, Germany or Britain.

In the mid 1880s in the Republic of Transvaal, otherwise known as the South African Republic, Britain found herself forced to sign a treaty as a defeated party for the first time since the American Revolution. The First Boer War had given the Dutch settlers, or Afrikaners, their own nation despite decades of conflict between themselves, the local African tribes, and the British Crown. Britain’s hostility only increased following the war as gold deposits were discovered in the Republic. With their newfound wealth, international interest – and capital – began to flow into the South African Republic.

Among those nations interested in improving relations was Germany. Beyond the South African Republic’s potential economic strength backed by their gold reserves, the new nation could potentially serve as a regional ally against British imperial designs on German African colonies. But where Germany saw their outreach as a mix of good diplomacy and smart strategy, Britain saw it as an implied threat. In March of 1897, as conflict between the South African Republic and Britain looked ready to ignite a Second Boer War (which would happen in 1899), Britain’s Foreign Office made it clear to Germany what would happen if the Kaiser intervened – a naval blockade.

German sailors peeling potatoes 1900 – the then-small German navy had embarked on a crash-course of production

The threat was a proverbial shot across the bow. Despite their economic dominance on the European continent, Germany recognized the vulnerability of their economy in the face of British naval dominance. In response, Germany began hurriedly producing warships on an industrial scale. Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, viewed as the veritable father of the Imperial Navy, pressed Berlin for passage of four Fleet Acts between 1898 and 1912, allocating 58 million marks a year with the goal of creating a navy at least 2/3rds of the size of the British fleet. For Britain, with their naval power now challenged – and British naval policy dictated by the “Two Power Standard” of the Victoria Era in which Britain’s fleet was mandated to be the size of the next two largest navies at all times – a similar naval output followed. Other nations – the United States, France and Japan – followed suit, and a worldwide naval arms race had begun.

In an effort to discourage foreign powers from continuing their naval expansions, Britain introduced the newest generation of warships in 1906 – the Dreadnought class. The Dreadnought was the culmination of various technologies which had been developing over the years. Larger, more armored and yet faster than any other battleship, the Dreadnought marked a generational step forward in naval weaponry. Carrying ten 12-inch guns that fired half-ton shells standing over 4-feet tall, each Dreadnought could in essence launch a small car 10-miles away and destroy an opponent’s flagship.

The HMS Dreadnought – the battleship revolutionized warship design, even though the Dreadnought class was quickly eclipsed by other, larger, ships by the end of World War I

Perhaps most impressive of all, the Dreadnought could be produced in a year’s time, whereas most warships required years of production. The British public clamored for more Dreadnoughts, voting down parliament’s Liberals who cautioned against the Dreadnought‘s price-tag (one Dreadnought could run anywhere from 1.7 to 2.6 million pounds while the national budget was only 256 million pounds). “We want eight and we won’t wait” was a popular cry as naval propagandists demanded more and more of the ship. As the Home Secretary, Winston Churchill wryly noted: “The Admiralty had demanded six ships; the economists offered four; and we finally compromised on eight.”

The diplomatic expectations of the Dreadnought were partially realized. By 1912, Germany’s commitment to the naval arms race was threatening their economy, as the cost to build an individual battleship rocketed up to 59 million marks. With the need to massively expand the German Army to match Russia’s millions, Berlin was eager to end the naval competition and relocate their resources. Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, who repeatedly misinterpreted British foreign policy, proposed a treaty in which Germany would accept British naval superiority in exchange for British neutrality in a future defensive war. The British refused, seeing no advantage of precluding themselves from intervening in a European war. Despite the hardline from London, Bethmann-Hollweg still halted Germany’s battleship production. The previous nearly 15 years of work had seen Germany manufacture 29 battleships, only to be outpaced by Britain’s 49 new warships.

Even with their numerical disadvantage, Germany had created a massive new navy – one that many of their officers were eager to test in the event of a war.

Kaiser Wilhelm II and his family pose in 1896, with his sons in naval uniforms. Wilhelm wrote that he “admired the proud British ships. There awoke in me the will to build ships of my own like these some day, and when I was grown up to possess a fine navy as the English”

By the beginning of 1916, Germany’s surface fleet had mostly been collecting mothballs. Despite the British blockade have frozen Germany’s international trade, slowly bleeding out the nation’s economy and starving the populace, the German High Seas Fleet sat at anchor in Wilhelmshaven by the North Sea. What offensive actions the Navy did perform were limited to U-boat attacks and Zeppelin bombings as Tirpitz believed the fleet was ill-equipped to challenge Britain on the open ocean.

With international pressure mounting on Germany to end their unrestricted submarine warfare, the High Seas Fleet factored back into consideration. As Germany’s political leaders ended the navy’s U-boat campaign in the spring of 1916, Tirpitz and his followers either resigned or retired out of frustration. A new generation of German naval officers would now take command, including the new Admiral of the High Seas Fleet, Reinhard Scheer. Scheer had argued against the defensive position of the fleet, preferring instead to conduct raiding parties on the English coast in the hopes of luring out British ships into a trap. Over time, Scheer argued, the British naval advantage could be chipped away, potentially ending the crippling blockade.

The first step towards Scheer’s new directive would occur with an incursion into the Skagerrak – the waterway between the Baltic and the North Atlantic, north of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula. The operation appeared simple with a high-degree of success – a small German fleet would ambush British merchant shipping until they triggered a British fleet in response. Then, operating so close to German waters, the small German fleet could be assisted by the rest of the High Seas Fleet and force losses on a Royal Navy stretched thin by global commitments.

Reinhard Scheer – a majority proponent of utilizing Germany’s surface fleet, Scheer changed his mind and embraced submarine warfare after Jutland

What Scheer hadn’t factored into his equation was that British intelligence had long since cracked the German naval codes. Using a captured German codebook the Russians had seized from a German cruiser that had run aground in 1914, the British Admiralty’s Room 40 was intercepting Scheer’s signals being sent to the rest of the fleet. Unfortunately, all Room 40 could determine was the High Seas Fleet was finally about to enter the war – not where, when or with how many ships.

The scale of the British response to the German High Seas Fleet was now entirely in the hands of the British Grand Fleet Admiral John Jellicoe. Having only held the post for less than two years, Jellicoe was already a public figure for his role in the relief of Peking during the Boxer Rebellion in which he was gravely wounded. Jellicoe had leveraged his newfound fame into Lord Kitchener-levels of publicity, with his image gracing all sorts of merchandise. But unlike Kitchener, Jellicoe was a politically indifferent commander who leaned heavily on caution. Unwilling to take a chance that the German incursion was merely a raiding party on British shipping channels, Jellicoe dispatched 151 combat ships to Jutland, including 28 Dreadnoughts. Win or lose, Jellicoe’s navy would not be placed at a numerical disadvantage.

HMS Queen Mary on fire and sinking

As Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty retreated towards Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet – a “run to the North” as British historians would later refer to the move – the British fleet left behind a trail of carnage. The HMS Indefatigable and HMS Queen Mary had both been sunk. Of the combined 2,000-man crews of the vessels, only 11 survived.

Jellicoe signaled the Grand Fleet that they were about to engage the German High Seas Fleet – the clash that both sides had sought after from the earliest days of both nation’s naval expansions. Only Jellicoe didn’t know that the near-entirety of the High Seas Fleet would be at Jutland. Room 40 had misread the signals they were intercepting, wrongly believing that Scheer was still at port in Wilhelmshaven. Scheer used a particular set of signals as the High Seas Fleet Admiral, but unknown to Room 40, changed those signals when at sea. Scheer’s shore-based signals continued to be transmitted by his office, unintentionally giving the impression that Scheer was commanding the battle from behind his desk. Thus instead of Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet awaiting Scheer, at first only the outgunned 5th Battle Squadron stood by to aid Beatty’s beleaguered ships.

For the next hour, the 5th Battle Squadron was forced to take on the brunt of the entire German High Seas Fleet with a handful of battlecruisers. Although most of the German battleships were pre-Dreadnought, meaning they were slower and less armored, they could still engage the battlecruisers at a greater distance. Caught between the small German fleet and the advance scouts of Scheer’s fleet, the 5th Battle Squadron took multiple hits without a loss, while dealing 13 direct hits to the Germans. They had accomplished their objective of buying Beatty’s forces time to join with the rest of Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet.

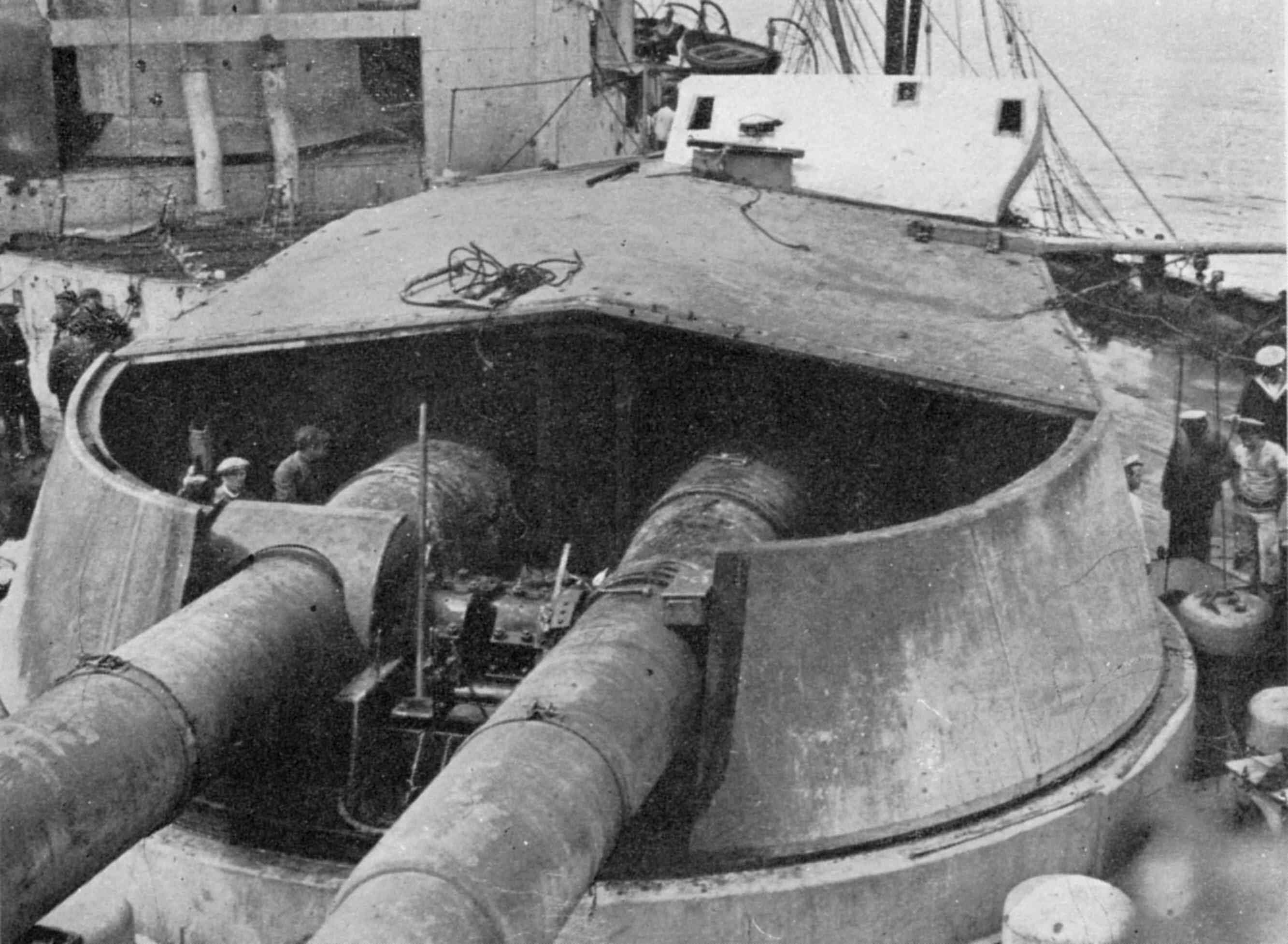

The damaged front turret of the HMS Lion – the flagship of Vice Admiral Beatty’s fleet

Jellicoe now knew that Scheer’s High Seas Fleet was engaged in the battle, but he wasn’t confident of Scheer’s position. Repeatedly, Jellicoe asked Beatty to confirm the location of Scheer’s ships as the Grand Admiral was receiving reports across the North Sea of German ship activity. Jellicoe’s caution was well-founded. The transition from the fleet’s cruising formation (six columns of four ships each) into a single battle line had to be well-timed. Too soon and the fleet would be significantly slowed and unlikely to be able to engage Scheer. Too late, and the Grand Fleet would open themselves up to allowing the Germans to “cross the T” with their fleet.

The alignment of battleships in a single line against an advancing fleet (the top cross line of a ‘T’) had been a staple of naval battle tactics since the innovation of rotating gun turrets. “Crossing the T” would allow vessels to use both their forward and rear guns, lobbing shells at an enemy formation with concentrated fire. Despite his doubts about Scheer’s position, Jellicoe would make the fateful decision to put the Grand Fleet into battle formation.

To the south, Scheer’s High Seas Fleet had fully formed and was sailing straight towards Jellicoe – completely unaware of the presence of the British Grand Fleet.

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe – his handling of the Grand Fleet at Jutland would be criticized

From Reinhard Scheer’s perspective, the Battle of Jutland had so far gone largely according to plan. The High Seas Fleet had been able to ambush a smaller British fleet, inflict casualties, and was now pursing them in hopes of creating greater losses. Instead, as the mist rose off the seas around 6:30 in the evening, emerging from the haze was Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet. Not only had the Grand Fleet’s presence in the North Sea completely surprised Scheer, but Jellicoe was already positioned to cross Scheer’s “T.” The entire German High Seas Fleet was in critical danger.

Scheer reacted immediately, turning his fleet to retreat so quickly that only 10 of Jellicoe’s 24 battleships had even managed to fire before Scheer began to run. But Scheer couldn’t put enough distance between him and Jellicoe to fully disengage and the British Grand Fleet continued to lob shells dangerous close to the German fleet. Even when Scheer sent his torpedo boats to harass the British in hopes of getting them to break off their pursuit, the British managed to stay in close quarters.

Desperate to end the battle, Scheer gambled – he would turn the fleet back towards the British. If the Germans couldn’t outrun the British, perhaps they could outfight them.

No, those aren’t ships on fire – they’re laying down a smoke screen, as the Germans would do to disengage from Jutland

The tactic didn’t faze Jellicoe. For the second time in 45 minutes of combat, the British crossed the German’s “T.” The Grand Fleet unleashed a much more concentrated level of fire, hitting five German battleships. Under the crushing weight of the British bombardment, the High Seas Fleet began to wilt, with the ships of the German line slowly falling out of formation. Scheer and his lieutenants tried to reorganize the fleet, but it was becoming obvious that the battle had decisively shifted to the British.

Recognizing his gamble had failed, Scheer attempted to disengage again, sending the rest of his torpedo boats and several battlecruisers to try and slow the British. The surviving Germans crews would call it “the death ride” as they fell under the guns of the entire British fleet. But as the German ships sacrificed themselves, Scheer and the rest of the High Seas Fleet were able to lay down a smoke screen and escape.

Throughout the night of May 31st and early morning hours of June 1st, Jellicoe attempted to find Scheer. Room 40 sent Jellicoe several messages accurately pinpointing the position of the High Seas Fleet, but having already been burned by naval intelligence earlier in the day, Jellicoe ignored the information. As the sun rose, the Germans had retreated back to their home port, the remains of 14 British and 11 German ships. along with over 8,500 sailors, littering the North Sea.

A German propaganda postcard detailing the losses at Jutland in order to show the battle was a German victory. Tactically it may have been, but strategically nothing changed

The High Seas Fleet had barely made it back to Wilhelmshaven before the German press declared victory. Under-reporting their own losses, Berlin declared Jutland (or the Battle of Skagerrak as it would become known in Germany) an unqualified success. A national holiday was announced and Kaiser Wilhelm II boasted to his sailors that they had “started a new chapter in world history” by defeating the famed Royal Navy. Even the British seemed to acknowledge their defeat, as the press sullenly compared British and German losses in the battle in between articles expressing shock that the vaunted Royal Navy had apparently lost the most significant naval battle of the war.

The fallout extended to Jellicoe. In both the media and military, Jellicoe was repeatedly condemned for allowing Scheer to escape. But Jellicoe aggressively defended his relatively cautious approach at Jutland. Britain held the naval advantage and the Germans had showed little inclination, despite the hyperbole of some members of their officer corps, to engage in a Trafalgar-like decisive battle. What advantage would Britain gain by forcing such a battle on the Germans? Even Winston Churchill, no great admirer of Jellicoe, partially defended the Admiral’s actions by stating that Jellicoe “was the only man on either side who could have lost the war in an afternoon.”

One of the wrecks of Jutland. It took until 2006 for the British government to designate these watery tombs as protected sites – long after they had been commercially salvaged and torn apart

As the weeks and months passed, Jellicoe’s caution would seem to have been well-founded. Despite Germany’s numerical victory at Jutland, the strategic situation on the North Sea remained the same – Germany was blockaded; their supposedly fearsome navy rusting away at port. The High Seas Fleet would only leave port twice more before the end of the war, but never again in such levels as present at Jutland. Scheer may had won a tactical victory, but the margin was too narrow to risk another battle. As one German naval expert stated of Jutland, “our Fleet losses were severe. On 1 June 1916, it was clear to every thinking person that this battle must, and would be, the last one.”

* The battles of the Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf ultimately involved more vessels, however most of the ships never saw each other in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, while Leyte Gulf was comprised of a series of smaller individual battles.

Fun reading the history of these ships, but it strikes me that for the most part, they were immense drains of funds that didn’t achieve much militarily. Maybe as big targets for opposing navies to concentrate on while the rest of the navy did the real work?

If I’m reading that right, might be a lesson there somewhere.

BB, the ships did their job. They were strategic weapons. They held the balance of power at sea just by being present. I guess you could consider them that era’s nuclear ballistic missiles. By not having those ships you cede control of ocean going commerce to the other side, and all the European countries of that era couldn’t feed themselves and depended on oceanic commerce to feed them and their troops. Absent the dreadnoughts on either side and the war was nearly a foregone conclusion to the side that had them.

And that is ultimately why Jellicoe made the right decision: his job was not to destroy the German Navy Nelson-style, his job was to make sure that the German Navy couldn’t get out and destroy British commerce. Unlike the situation at Trafalgar, the Germans were retreating, not advancing, so while Nelson was essentially forced to throw the dice and attack the larger force to prevent an invasion of England, Jellicoe’s job was to keep the status quo that would slowly grind down Germany. Glamorous and self-aggrandizing his decision was not; I wonder if Nelson would have made the same correct decision.

It was career limiting for Jellicoe and he did pay the price for his decision, but ultimately Churchill was right about the risk of catastrophe had Jellicoe engaged the German fleet and lost. And what was the upside even in a complete victory over the High Seas Fleet? Keeping the German High Seas Fleet in port was the same as sinking it in strategic terms. It sucks to be the adult in the room sometimes.

Keeping the German High Seas Fleet in port was the same as sinking it in strategic terms.

Militarily yes, strategically – not quite. Germany gained the upper hand in the propaganda wars. A complete victory would have translated into a bigger strategiric advantage for the Brits.

JPA, yes, quite right. Sinking the fleet would have changed the overall strategy and allowed more resources to flow from the navy to other areas, too. But still, the risk involved in chasing a fleet into its home waters where shoals, shore batteries, mines, and coastal craft would come into play was too great a risk for Jellicoe to take. He had the upper hand and keeping the Germans out of the Atlantic was more important than sinking them.

As to the propaganda effect of the battle, that’s basically why Jellicoe paid a price and was taken away from direct command of the fleet. The Brits expected their admirals to be Nelsons and victories to be inevitable, but the right strategic decision in this case was the cautious one that Jellicoe made.

(Halsey nearly lost the Battle of Leyte Gulf by being too aggressive and falling for Ozawa’s lure, but the overall command and communication structure of the whole Philippines invasion was a clusterfark anyway.)

Makes some sense, Nerdbert, but it strikes me that the Germans somehow managed to interrupt commerce a bit during the Great War with other, smaller ships, no?

Pingback: The Rock Amidst the Raging Tempest | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: Kiel Over | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: To The Last Man | Shot in the Dark