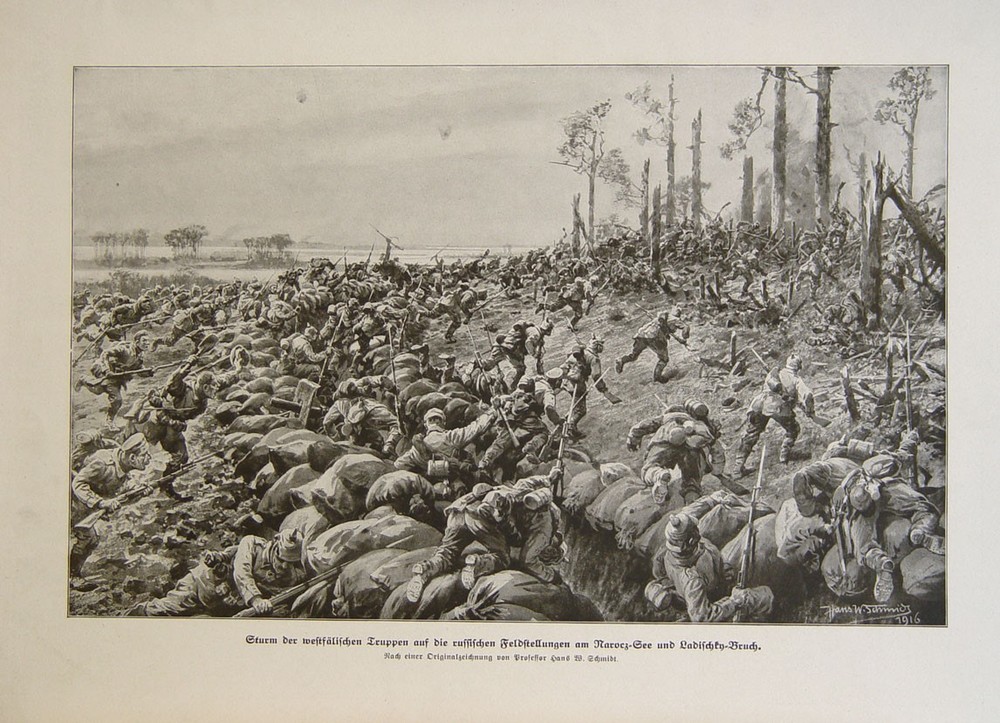

What had been a roar of artillery weeks earlier had quieted to a trickle of distant, infrequent thuds. Where the men of the Russian Second Army had charged forward over snow-capped passes days earlier, on March 31st, 1916, survivors now limped back through a morass of mud and blood at Lake Naroch, in what is now modern Belarus.

It should have been a momentum-changing victory for Russia and the Entente. Eager to recover from their rout in the summer of 1915, 373,000 Russian soldiers had attacked only 82,000 Germans holding one of the weakest portions of the Eastern Front. 887 pieces of field artillery had pounded the German line for two days – an eternity by Eastern Front standards – under a battle plan crafted by the Russian Imperial Army’s own Chief of Staff. The Russians had optimistically believed they were about to achieve their breakthrough.

Instead, it was yet another major Russian defeat. Only this time, it had the fingerprints of the rest of the Entente all over it.

—

Lake Naroch carried all the hallmarks of early Russian defeats – bad intelligence, terrible tactical execution, and overconfidence. The difference was the Russians thought they had addressed these issues before the battle

The seeds of the Russian debacle at Lake Naroch had been planted months earlier in the French city of Chantilly. Indeed, many of the Entente defeats of 1916 could trace their lineage to the Inter-Allied Conference at Chantilly in December of 1915.

For the nearly one-and-a-half years of the Great War, the Entente had embarked upon offensive operations with little to no central planning between the major powers. Save for the Anglo-French cooperation in France, and less so in Salonika, a larger coordinated strategy to win the war had yet to materialize. In the eyes of the French Commander-in-Chief, Gen. Joseph Joffre, the Entente had been fighting at cross purposes. Only together could they possible inflict offensives that had a chance of defeating the Central Powers.

At Joffre’s headquarters in Chantilly, representatives of the Entente’s major powers – Britain, France, Russia and Italy – gathered to lay out a coordinated strategy for 1916 and beyond.

The Chantilly Agreement – “coordination” quickly became code for “doing what the British and French wanted”

In principle, Entente coordination was supported by all of the representatives, including Russia. And why not? If all four powers could launch attacks at once, they might be able to achieve a decisive breakthrough somewhere. In execution, the Entente’s concept of “coordination” largely devolved into obligating each member of the Alliance into conducting last-minute offensives if asked to by another member. And in practicality, the conference had affirmed the diplomatic and military dominance of Britain and France at their allies’ expense. Despite their armies being stretched to their breaking point, the Russians and Italians were forced to contribute men to Salonika and France. The Chantilly Agreement, as it would come to be known, contained a “poison pill” for Entente members who refused to “coordinate” as the British and French wished – supplies and armaments would be cut.

Russia’s and Italy’s military planning was now being dictated in London and Paris.

—

Russian artillery hammers the German lines – or so the Russians believe

The Chantilly Agreement would be put to its first test with Verdun.

As France bled in their protracted duel with Germany, Joffre invoked the coordination clause of Chantilly in a desperate bid to lure German units away. For most of the Entente, the response resulted in either delayed or minimal attacks. The Italians would be the first to respond, attacking Isonzo for the fifth time since May of 1915. But within six days, the Italians would stop their token effort, having lost 1,900 men. The British wouldn’t attack until the summer at the Somme, albeit an attack to that led to among the worst bloodletting of the entire Great War.

The Russians intended to honor not just the letter of the Chantilly Agreement, but its spirit. A major offensive at Lake Naroch had already been contemplated, as the Russians knew they significantly outnumbered German forces in the area.

The attack had been the brainchild of Mikhail Alekseyev, the Russian Army’s Chief of Staff. Born to a poor private, Alekseyev had advanced in the Imperial Army due to being a smart and ambitious officer. In functionality, Alekseyev was the nation’s Commander-in-Chief. Despite Tsar Nicholas II having officially taken over the duty in the early fall of 1915, Nicholas had little concept of the organizational nightmare of running such an army – Alekseyev did.

Gen. Mikhail Alekseyev – historians criticize Alekseyev’s limited strategic creativity, but he was able to partially address Russia’s abysmal military infrastructure

Alekseyev had taken a number of factors into consideration. The logistical challenges of transporting supplies in the winter were dealt with – Russian gunners would have their shells, and Russian soldiers plenty of ammunition. Diversionary assaults against the Austrians would keep the Central Powers confused. But the one factor Alekseyev hadn’t fully considered was the incompetence of the Russian officer corps.

—

The Russian bombardment that started on March 18th, 1916 went according to plan. The shelling lasted for two days, as intended, and the 373,000 men of the Russian Second Army rushed forward in anticipation of claiming their victory.

The bombardment had missed its mark. Badly. Little of the German front lines had been affected by the shelling, and the Germans, although vastly outnumbered, were in far better fortifications than Russian intelligence had believed. Russian troops moved forward in human wave formations, a tactic that been disregarded in the West many months earlier because of the easy targets such waves made for machine guns. The Russians were mowed down by the thousands without so much as sniffing the German trenches. In response, the Russians attempted to attack at night – using searchlights to blind the German line. The tactic had worked against the Japanese in the Russo-Japanese War 11 years earlier. But at Lake Naroch, the searchlights only served to silhouette the advancing troops, making them even easier to shoot.

German trenches – the Germans had mastered trench building techniques and the Russians had badly underestimated how fortifications could help a smaller force withstand an assault by a larger army

Even the elements were refusing to cooperate. Spring rains turned the mushy snow into mud, making reinforcement or advancement all but impossible. Communications between Alekseyev and his commanders broke down. The lack of passable roads made receiving orders difficult, and the lack of success emboldened the aristocratic generals to defy the poor private’s son. When it was over, what minimal gains the Russians had made were quickly undone in the weeks to follow. 110,000 Russians had been added to the casualty rolls, 12,000 of them from inadequate winter clothing. The Germans lost 20,000 men. Anticipating a major victory, the Russians were reduced to arguing that they had inflicted greater losses than the Germans were willing to admit.

Most importantly, the objective of the entire operation – drawing German forces away from Verdun – had failed.

—

Russian POWs at Lake Naroch – 3.3 million Russians would end up as prisoners of war between 1914 and 1917

For all the failures at Lake Naroch, the Russians had actually learned a few key lessons.

The first, and perhaps most important, was that future offensives would be better served to target the Austro-Hungarians than the Germans – the diversionary assaults for Lake Naroch gained more ground than the main offensive. Second, the Russian High Command could organize a decent attack. Alekseyev and the General Staff had managed a solid battle plan, and overcame Tsarist Russia’s inferior transportation system (not to mention material shortage) to properly arm their men. The Russian soldiers may have risked freezing to death at Lake Naroch, but they had enough guns and ammunition for the task at hand. For an army nearly 2 million rifles short, and accustom to sometimes sending men into battle only with ax handles (not axes, ax handles), having enough supplies was a major accomplishment.

Lake Naroch also revealed that Germany was becoming dangerous arrogant about the disposition of their own forces in the East. German aerial units had spotted the Russian build-up weeks in advance, but did nothing to shift their forces in response. A year-and-a-half of lop-sided German victories against the Tsar’s malnourished army had seemingly convinced not only the General Staff in Berlin, but the generals on the ground on the Eastern Front, that Russia was incapable of launching successful offensive operations.

The offensive at Lake Naroch had fallen short due to rushed planning and poor tactical execution. Given enough time, and the right commanding officer, the Russians might have a chance to win a victory on the Eastern Front. Unfortunately, one key person didn’t believe that was possible – Alekseyev. The Chief of Staff had become racked with self-doubt in the wake of his defeat, communicating his newfound belief that Russia no longer held the ability to go on the attack.

That summer, with a more successful and confident general in the lead, Russia’s fortunes in the Great War would change.

Thank you. You would be surprised (or maybe not), how little was taught about WWI in Russian (soviet) schools. It was like that war was just a passing wind without a consequence. And, that picture of the german trench brought back memories and a realization. I was probably playing in those same trenches 60 years later, thinking they were from WWII but they were more likely from WWI. Again, thank you.

Pingback: Moscow on the Mediterranean | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: Disastro | Shot in the Dark