The inhabitants of the sleepy Mesopotamian village of Kut al Amara (or Kut for short), might have felt like strangers in their own homes on December 7th, 1915. Situated on the banks of the Tigris river 100 miles south of Baghdad, the 6,500 residents of Kut were certainly used to people passing through, albeit usually via the river. But the latest visitors to Kut had mostly arrived by land – well over 13,000 of them – and were starting to make themselves at home. Trenches and bulwarks were being created overnight; tents flooded the village and surrounding river banks.

The newest guests to Kut were a collection of British and Indian troops who had last passed through the village attempting to claim Baghdad, and all of Mesopotamia, for the Crown. Now in headlong retreat, the British and Indians had chosen to dig in and allow themselves to be surrounded by their Ottoman pursuers. It had been the the brainchild of an arrogant British Indian Army General who preferred taking his orders from New Delhi than London, and was being executed by a British General whose claim to fame had been enduring a similar siege in Pakistan years earlier.

The strategy to conquer Mesopotamia had been ill-conceived and hastily implemented. Now it was about to become, in the words of one British military historian, “the most abject capitulation in Britain’s military history.”

—

The Siege of Kut – many of the troops that held Kut for 147 days would never return home

Had the War Office in London gotten their way, Britain’s involvement in the so-called “Cradle of Civilization” would have ended in November of 1914.

With the British Navy needing access to oil to fuel their fleet, the capture of the port city of Basra and its oil fields in the late fall of 1914, in addition to the joint British-Russian division of interest in Persia, would have eliminated the need for anything more than a defense force to ensure the territory still raised the Union Jack. Coupled with assistance from the ruler of Kuwait in return for a recognition of independence from the Ottomans, the British had secured the fuel needs for their war effort while the Ottomans kept to themselves at Baghdad, some 275 miles away.

In the spring of 1915, the Ottomans, frustrated with their inability to win on any front and worried about the Allied invasion of Gallipoli, changed their strategy – they would take the offensive against the British in Mesopotamia. The result was a series of one-sided British victories so complete that the Ottoman general in charge shot himself in shame. With less than 10,000 soldiers at their command, the British had advanced deep into Mesopotamia and vanquished an enemy with several times the number of troops.

The Ottoman Army of Mesopotamia. Originally poorly organized and led, the Ottomans wasted their initial numerical advantage against the British

The victories elated London’s politicians, but the advances of the British Army worried the War Office. Gen. Sir John Nixon had been sent to Basra to take command following the Ottoman offensive. An old guard British Indian officer, Nixon routinely didn’t inform London of his orders, preferring to tell his British Indian superiors who green lit Nixon’s penchant for the offensive. Some of it wasn’t intentional – British Indian officers had typically operated without oversight from London. But then typically British Indian officers were fighting tribesmen at the edges of the empire, not a European-styled army in a global war. Victory spoiled any appetite Nixon had for caution – he would drive as far as he could get away with.

Coming at a low point for the Entente, Nixon’s aggressive insistence that he could be in Baghdad by Christmas boosted London’s support for his strategy. Even Lord Kitchener, who typically held some reservations, surrendered to the momentum of a Baghdad push and gave it his wholehearted endorsement. With the arrival of thousands of troops from the Indian Expeditionary Force D, the British were now determined to drive the Ottomans out of the Fertile Crescent.

—

“Chitral Charlie” – Gen. Charles Townsend had become famous for his defense of a fort in what is now Pakistan. He believed he could recreate the event in Kut

When it came to their military heroes, the British often appeared to suffer from a certain attraction to fatalism.

British history, particularly in the period of colonial expansion, was rife with examples of doomed, outnumbered British soldiers vainly holding out until being overwhelmed. Charles George Gordon was an eccentric officer who probably had no business commanding men in battle. He died “Gordon of Khartoum” in a siege against Sudanese tribesmen. Gen. William Elphinstone’s fight to hold Kabul against an uprising of Afghans had been a strategic folly, but the resulting defeat, known as the “Massacre of Elphinstone’s Army,” made him a legend in the press. The battles of Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift in the Zulu War further inspired a generation of young Britons, even when the results were thousands of British dead.

Gen. Charles Townsend was already a semi-famous figure in Britain for just such a battle. The commander of a surrounded garrison of only 400 men in Chitral (now modern Pakistan) in 1895, Townsend and his company had endured a month-and-a-half siege before being relieved. Members of the “Chitral Relief” earned medals and glories at home, with Townsend basking in the brief limelight as “Chitral Charlie” before serving without distinction in the Boer War.

British Indian Troops – the Indian Expeditionary Force D. Forces B and C had been sent to East Africa while Expeditionary Force A arrived in France in early September

Sir John Nixon had tasked Townsend with the advance towards Baghdad, and Townsend had moved up the Tigris with relative speed and skill. The Ottomans had been at the mercy of their own officer corps, lacking a German adviser as so many of the best Ottoman units had. Inexperienced, or just plain ineffective, the Ottoman response to the British advance had been timid and repeatedly brushed aside. Desperate to stop the British before they reached Baghdad, the Germans sent 72-year old Baron von der Goltz, a famed German military historian, to take charge.

Goltz wouldn’t arrive before the decisive battle of the campaign. At Ctesiphon, 25 miles south of Baghdad, Townsend would fight against Col. Nureddin Pasha. Known to his men as the “Bearded Pasha,” Nureddin prepared his defenses carefully and threw most of the remaining weight of the Mesopotamian army against Townsend’s forces. After five days of fierce fighting, and down to his last 8,500 healthy troops, Townsend retreated back towards Kut to regroup and refit. Nureddin, eager to exploit the Ottoman army’s first victory of the war without German advisers, pursued.

Happier Times – the British on the march in Mesopotamia

Ctesiphon hadn’t broken Townsend’s army. Morale and supplies were most certainly down, but the army had retreated in an organized fashion. Upon learning that the Ottomans were in the process of trying to surround Kut, Townsend could have still easily escaped and moved further south to meet the reinforcements Sir John Nixon was starting to dispatch. But doing so would abandon ground gained. Doing so would also mean losing the opportunity for another valiant British siege.

Townsend would dig in at Kut and await his fate.

—

Upon allowing himself to be surrounded at Kut, Townsend notified Nixon that the situation was dire – there were only enough food supplies for one month. That was the last urgent communication from Townsend until nearly the end.

Townsend at Kut – the General kept mostly to himself, worrying more about his reputation than the siege

In truth, the British situation at Kut was tolerable. The Tigris river banks gave the British a good defensible position and the river itself acted as a communication line with the main British base at Basra. The current food supplies could easily maintain the British for at least four months – and that was assuming the British didn’t ration. In addition, there was dissension in the Ottoman ranks. Baron von der Goltz’s arrival at Kut frustrated the Ottoman officers present, who resented a German potentially taking the credit for their impending victory. Col. Nureddin Pasha would finally be dismissed after refusing Goltz’s orders and trying to get the old German replaced. “The Iraq Army has already proven that it does not need the military knowledge of Goltz Pasha,” Nureddin complained.

Regardless of the situation at Kut, it didn’t look like Townsend and his men would be there for long. 19,000 British soldiers had started marching towards Kut at the start of January. Huddled in his headquarters, living in relative luxury, Townsend issued breathless communiques of his bravery and waited to be rescued. “Chitral Charlie” was rapidly becoming “Townsend of Kut.”

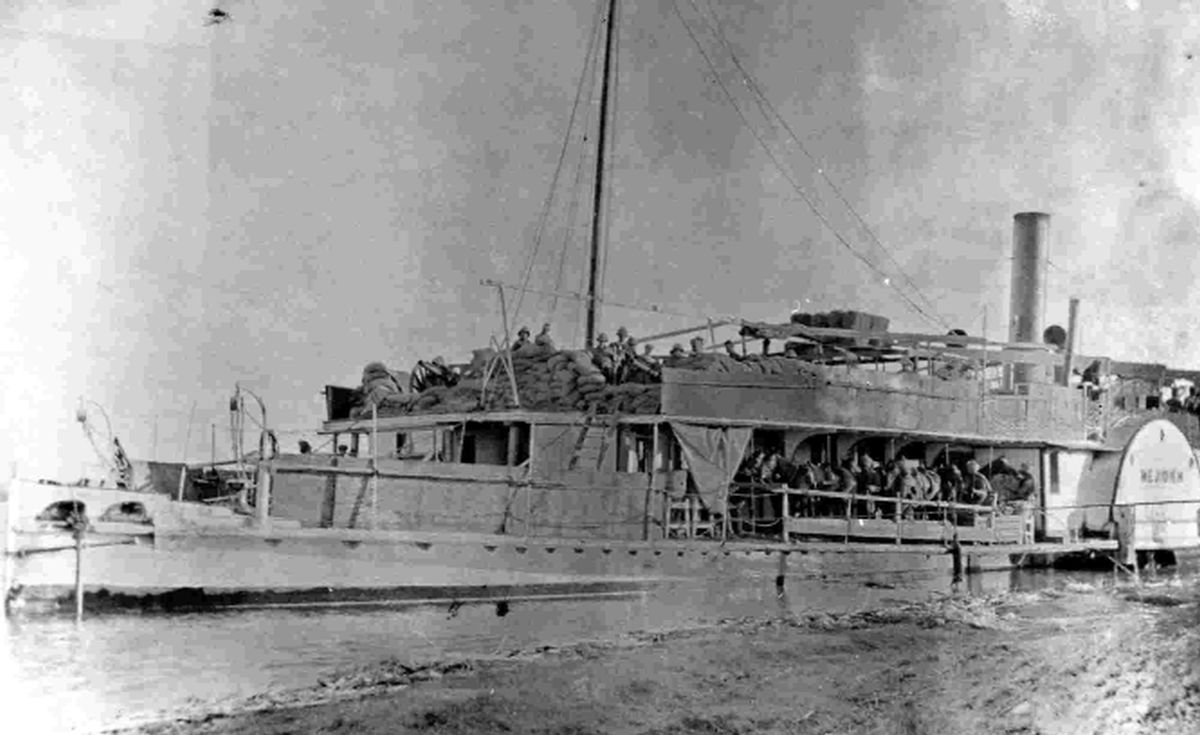

Paddleboat Relief – the only way for supplies to reach Kut was via the Tigris, and even that was extremely difficult. By the end of the siege, the first plane-dropped supplies in war had been sent

Except the rescue wasn’t coming. The British march from Basra hit a massive roadblock with their defeat at the Battle of Hanna in late January. The men inside Kut could hear the artillery bombardment as 10,000 British and Indian troops threw themselves against the Ottoman defenses. Despite his subordinate’s resistance to his leadership, Goltz knew how to conduct a defensive campaign. With 30,000 additional troops moved south of Kut, the Ottomans had almost every advantage. And as the British survivors of Hanna froze in the cold desert’s aftermath, losing 2,700 men in the process, any hope for a relief of Kut melted away. The 19,000 man effort was broken as a fighting force. Townsend was on his own.

—

Townsend handled the crisis with a flare reserved for the kind of eccentrics rarely found outside the British officer corps of early 20th century.

Kut in 1916 – either a small city or large village of 6,500, Kut today has over 183,000 residents

Townsend viciously beat his man-servant, Boggis, for the crime of Townsend’s dog snuggling up to Boggis in the middle of the night. During one of the many Ottoman attempts to break the British line, Townsend stripped naked in the mid-day sun to change his uniform, all while eating a piece of plum cake and observing the shelling. He demoted an artillery captain for the outrage of having spotted Goltz and firing a few shells at the German.

As the situation deteriorated, Townsend rarely left his two-story villa, preferring to walk his dog around the courtyard and receive visitors. While his men survived on five ounces of bread and whatever meat the cooks could get from butchered mules, Townsend ate three square meals a day. The news of his behavior would only surface years later when Townsend leveraged his time at Kut into a brief political career.

In the meantime, there were still faint hopes of somehow rescuing Townsend’s men. The British couldn’t possibly put together yet another force to march north, but other ideas were tried. The Russians were implored to move out of Persia and march to Baghdad, perhaps forcing the Ottomans to lift the siege. Several British officers, including a pre-fame T.E. Lawrence even secretly approached the Ottomans with a 1-million pound ransom if they let the soldiers at Kut go free. Apparently no idea was too far-fetched.

The Prisoner as a Trophy – Townsend (seat, far left) in an Ottoman propaganda picture

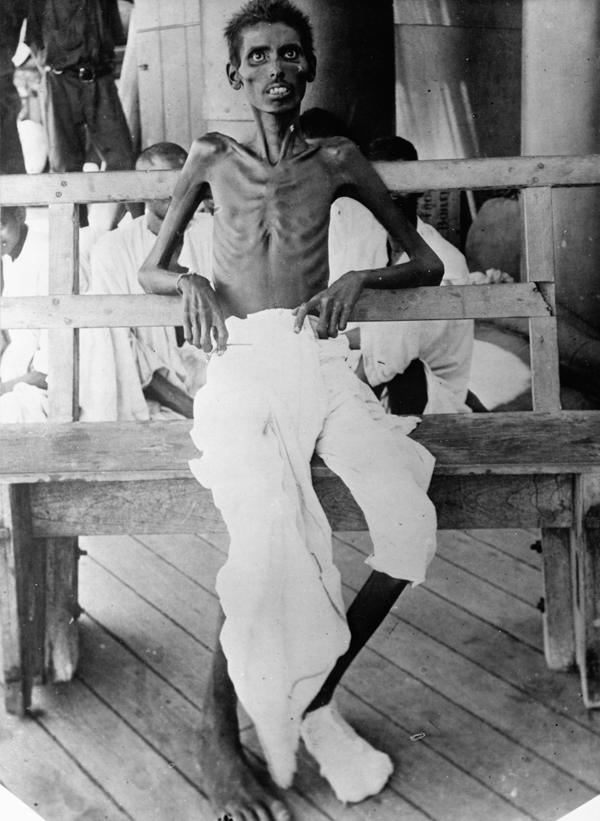

By April 29th, 1916, it had all been too much. With no relief force in sight, and with men dying in the streets, Townsend surrendered. 13,000 men, most of them too weak to walk, entered Ottoman captivity. Goltz had died just days earlier of dysentery and his Turkish successors were not in a forgiving mood. After separating the British officers from their men, the Turks forced the soldiers to march nine miles to a new POW camp. Those that dropped from exhaustion were left to die and those who made the hike were repeatedly beaten. One-third of the prisoners of Kut died after their surrender, many out of sheer Ottoman brutality.

Townsend saw none of it. He was treated as royalty by the Ottomans, who eagerly held him out as their star POW. After being the guest of honor at a banquet in Baghdad, Townsend spent the remaining years of the war on the island of Halki in a villa that outstripped the one he held in Kut. Townsend was so enamoured with the setting that he repeatedly tried to convince his wife to join him as a prisoner. The images of Townsend’s luxury outraged the War Office while “Chitral Charlie” could never understand why he was greeted with such hostility after the war.

—

An Indian POW – 50% of the Indian POWs died in captivity, either from disease or Ottoman abuse

A third effort by the British would finally capture Baghdad in March of 1917, but not before 92,000 British and Indian soldiers would become casualties in perhaps the most completely unnecessary front in the entire Great War.

The British obsession with teritary fronts had already cost the Entente hundreds of thousands of men, but most of the other fronts had at least some semblance of importance. The strike at Gallipoli had become a massive embarrassment, but had it worked, the Ottoman Empire would have pushed out of the war and the Western Allies could have supplied the Russian army through the only clear waterway not impeded by German U-boats or ice. Salonika was so useless the Germans called it their “largest POW camp,” but the invasion had been to prop up Serbia and possibly force Greece and Bulgaria into the war for the Entente. Even some of the battles in Africa made more sense as the Germans threatened key colonies or the Ottomans attempted to whip up anti-British sentiments.

Eventual Victory – the British marching into Baghdad in March of 1917

But the campaign in Mesopotamia served no larger role in the war. Capturing Baghdad would not – and did not – drive the Ottomans out of the war. Indeed, the Ottomans would continue fighting for nearly 19 months after the city fell. Baghdad would have made for a poor launching point for further invasions of the Ottoman Empire as it was at the end of a very long, and very poorly maintained, supply line. But in late 1915, the British, as well as the entire Entente, was desperate for a victory. Any victory, anywhere.

Kut would be the beginning of a very long, and very dark year, for the Entente.

Pingback: A Slice of Turkey | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: The Rock Amidst the Raging Tempest | Shot in the Dark

Pingback: Mirage | Shot in the Dark