It was a little before 9am in the morning as Mamoru Shigemitsu, Japan’s foreign minister, and the rest of the Japanese delegation, boarded the massive American battleship the USS Missouri on September 2nd, 1945.

The small Japanese contingent was dwarfed by the presence of the American military, and the number of representatives from other Allied forces. 89 warships, the majority American but a handful of them British, lay at anchor in Tokyo Bay, while hundreds of American planes flew in formation overhead. The deck of the Missouri itself was overflowing with brass and press, the occasion dripping in symbolism of the American military might than had finally brought Japan to surrender.

At 9:04am, Shigemitsu signed the Instrument of Japanese Surrender on behalf of Emperor Hirohito. In a small form of irony, Shigemitsu had been among the few prominent figures in the government to oppose a war with the United States (Japan’s militarists never trusted him) and yet stood signing for a surrender to a war he had never wanted. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, milking the moment, signed as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces before turning the pen over to the representatives of the other Allied nations. By 9:23am, the signatures had been completed and the brief ceremony finished.

World War II had ended. The challenge of the post-war world had begun.

—

The formal Japanese surrender – the actual ceremony was very brief

Defeating the Axis powers had been a monumental task, won at the cost of perhaps 50 million dead or more (some estimates range as high as 80 million). Rebuilding those same powers would prove to be a nearly equal task.

History had few guidelines to rebuilding an enemy nation. Armies of occupation had existed as long as there had been warfare, but typically the outcome was annexation, or as the case of the Great War armistice just a generation earlier – occupation, negotiation and then eventual evacuation. Short of instituting puppets or colonial governments, none of the Allied powers had a ready-made model for reconstructing the post-war societies of Germany, Italy and Japan.

Indeed, the challenge of the post-war wasn’t merely political – it was cultural. For appointing new leadership was meaningless if the societies that produced Nazism, Fascism and the ethics of bushido weren’t fundamentally altered as well.

—

Japan: Shogun and “Shikata Ga Nai”

The challenges of cultural reinvention would be put to the greatest test with the last Axis power to surrender. If the war had crushed the political systems of Germany and Italy, Tokyo’s choice of unconditional surrender over invasion left the Allies with a perplexing problem – a still functioning enemy government led by a sovereign who had retained public credibility.

The fate of Emperor Hirohito had long been the excuse of Japan’s most militant leaders to avoid ending the war. With Allied public opinion wishing to prosecute Hirohito in the same manner as the other war criminals of the Axis, the fate of the Emperor, and the entire Meiji Dynasty rested in the hands of one man – Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

MacArthur and Hirohito

While the structure of the occupation of Japan was intended to remain similar to Germany – division of territory and delegation of authority between the Allied powers – in practicality, Douglas MacArthur ruled as a modern American Shogun (the title of an excellent book on the subject). Misgivings about allowing the Soviets into Japan (they were suppose to occupy the northern Japanese home island of Hokkaidō), coupled with MacArthur’s own force of personality and political connections at home, provided a perfect recipe for allowing the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in the Pacific a free hand in both crafting both American and Japanese policy. No one – not the other Allied nations, the Japanese government, nor even the U.S. government – could or would provide a check on MacArthur’s designs.

Those designs started with remaking the image of Emperor Hirohito. Whether MacArthur saw a weak-willed puppet or a ruler desperate to maintain power in Hirohito, the pair skillfully used one another to maintain and enhance their positions in post-war Japan. Posing together for a photograph in late September, the historic picture laid the groundwork for the narrative of the next six years and beyond. Hirohito’s appearance of subservience would subtly demonstrate that the real power in Tokyo was in MacArthur’s hands. And MacArthur, in making Hirohito look diminutive both in size and stature, helped portray the Emperor as weak, crafting the post-war narrative that the young monarch had played little role in his country’s expansionist wars. While Hirohito’s true culpability for the war will remain lost to history, both he and MacArthur were eager to embolden the concept of the Emperor as a pawn if it assured cooperation from the Japanese, and protection for the royal family from prosecution.

Soviet troops in northern Korea

With Hirohito supporting his position, MacArthur went about overhauling the rest of Japanese society. A new constitution, with significant input from MacArthur’s team, was hurriedly rushed through the Japanese Diet, empowering the legislature and reducing the monarchy to a symbolic status. Economic, social and political liberalization was force-fed into Japanese society (surprisingly in some cases, given MacArthur’s known conservatism) and within a short eight months after the end of the war, Japan had elected their first post-Empire Prime Minister. The nation appeared to be on a fast-track towards recovery.

But such massive transitions also brought strife. Over 5 million native Japanese returned home after the war – many of them settlers on islands or in China who had been forcibly removed. Crime and poverty skyrocketed in the cities, and MacArthur’s attempts at land reform in the rural countryside produced an effect not unlike the end of serfdom in Russia in 1800s – angering the nation’s wealthy while pushing poor farmers onto tracks of land they couldn’t afford to own. The state of affairs became so despondent for some that the phrase “shikata ga nai” (“nothing can be done about it”) started to become the nation’s unofficial mantra.

Not until the Treaty of San Francisco in 1952 did Japan fully regain their sovereignty.

New Zealand Troops have a laugh with Japanese children. The raping and pillaging that the Japanese were taught to expect at the hands of the Western Allies was quickly proven to a myth

—

Italy: The King of May

Italy’s post-war experience, short of the expulsion of Communists from parliament as part of the broader Cold War narrative, has been largely forgotten. Unlike Japan, the war had left Italy with neither a fully-functioning government nor a monarchy with any credibility with the general populace.

The unmaking of the Italian political system had been a slow-moving car accident. In the wake of Italy’s switch to the Allied side, King Victor Emmanuel III went from a somewhat popular, if aloof, figurehead, to the embodiment of Italian weakness. The monarchy had long worked to keep its distance from Mussolini and Fascism – despite willingly embracing the man and the movement when it resulted in victories like Abyssinia and Albania. Now, as the nation was divided by foreign powers and internal schisms, the Italians attempted chart a path forward with a new ruler.

Umberto II – Italy’s last monarch. Umberto was infinitely more popular than his despised father, Victor Emmanuel III, but rumors of his supposed homosexuality (and his father’s ego) kept him from assuming the monarchy until it was too late

In the spring of 1944, Victor Emmanuel III turned over the reins of power to his son, Umberto, as Lieutenant General of the Realm. Soon afterwards, Umberto announced that the fate of the monarchy would be left up to the people – a constitutional referendum would be held on whether to maintain the monarchy after the war. The move was less an abdication than an appeal to unite the country under a younger, more charismatic ruler, with fewer messy ties to the Fascist era.

Umberto’s political ties to Fascism were seen as less complicated than his father’s, despite Umberto’s somewhat prominent role within the Italian military, including the command of Army Group West, which led the “invasion” of southern France in 1940. But it was Umberto’s personal affairs that threatened his would-be position as King. Although Umberto was married to the King of Belgium’s daughter, the two lived entirely separate lives – quiet literally. If not for their four children as proof, one could have assumed they almost never met again after their arranged marriage. Such martial distance, and Umberto’s preference for living among soldiers, started rumors that the Italian heir was homosexual. Aided by supposed documentation gathered by Mussolini’s spies, Umberto found himself repeatedly forced to reaffirm his sexual orientation.

But it was internal politics, not sexual politics, that was dooming the Italian monarchy. By April of 1946, polling by the monarchists in the post-war government revealed an overwhelming support towards a constitutional republic. 60% of Italians claimed to support a republican government, with only 17% wishing to keep the monarchy intact. Desperate to keep the House of Savoy in power, Victor Emmanuel III formally abdicated to his son. Now installed as Umberto II, the 40-day reign of the “King of May” began.

A Pro-Monarchy demonstration – oddly, even though the House of Savoy (and most Italian royalty) came from northern Italy, southern Italy was the biggest supporter of the monarchy

Umberto II put a youthful and energetic face on Italy’s sagging monarchy, as the new King began a whirlwind tour befitting a political candidate, trying in vain to influence the constitutional referendum without looking like he was doing so. The tactic worked. Huge crowds greeted the new monarch and his wife, momentarily putting Italy’s Fascist past (and Umberto’s sexual rumors) into the background. Nor did it hurt the monarchist’s cause that the pro-republic vote was being supported by both the communists and what remained of Italy’s fascists, both of whom committed acts of violence against monarchists in northern Italy. As millions of displaced Italians attempting to stream back to their homes in time to vote, what was once a forgone conclusion looked to be a genuinely close vote.

With an 89% voter turnout, Italy chose a republican government – 54% to 46%. The choice of govern had literally divided the nation – the northern provinces had backed the republic in the 60% range, while the southern regions supported the monarchy by similar margins. In the interest of avoiding any lingering dreams of restoring the monarchy, and thus further dividng the country, Umberto II voluntarily left Italy. He would never set foot on Italian soil again.

Italians apparently hold long grudges. In the wake of the constitutional victory, Italy passed new amendments barring all future male heirs to the House of Savoy from entering Italy. Umberto II was refused even burial in his homeland, while his son, Vittorio Emanuele would become the first male member of Italian royalty to return to Italy in 2002. Vittorio was only allowed to enter Italy because he was visiting the Pope, and had to publicly renounce any and all claims to the nonexistent Italian throne.

Umberto in Exile – the former monarch looks wistfully at the ocean while in exile in Portugal

—

Germany: Divided and Conquered

If the Allies were eager to get Japan and Italy back to being fully-functional, independent governments, the exact opposite was true in regards to Germany.

And why not? For the second time in a generation, Germany had been responsible for a global war (and most assuredly singularly responsible this time). Perhaps over 100 million people had perished between both conflicts – roughly 5.5% of the world’s population from 1914. The desire for punitive measures, even in the West, ran high.

Punitive measures hardly seemed necessary given that what remained of the German State was in shambles when Karl Dönitz’s makeshift government surrendered to the Allies on May 8th. Their infrastructure pounded into dust, the average German civilian was surviving on less than 1,200 calories a day. To compound the situation, 12.4 million Germans had been expelled from Eastern Europe by the Soviets, flooding a nation that couldn’t feed it’s current population. American supplies had estimated needing to feed 7.7 million German civilians and POWs, and when the reality of the crisis didn’t meet U.S. planner’s expectations, the evidence was ignored. Even as the mortality rate for German infants increased ten-fold, American authorities forbid transferring additional food into Germany. 1/6 of the American food supply was already being transferred overseas, but between the difficulties of transporting supplies, and a strong black market that benefited from keeping Germans hungry, the end result was millions of Germans slowly starving to death.

Deported Polish German children. Only 300,000 ethnic Germans chose/were allowed to stay in Poland. Nearly 2.5 million ethnic Germans died from being displaced

The exact number of German dead after the Second World War is unknown and highly controversial, but estimates as high as 9-11 million (if one factors in German POWs), probably aren’t wildly off.

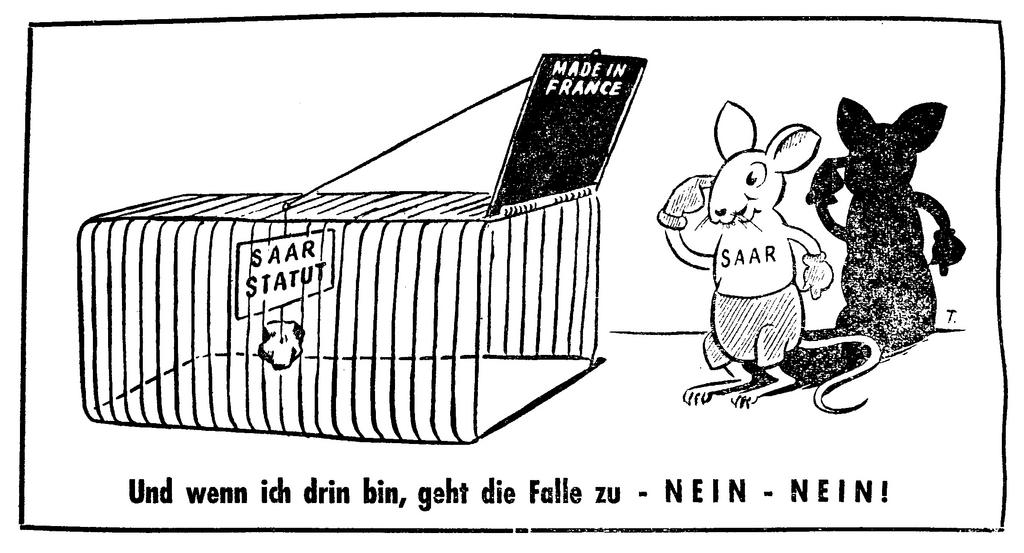

While the German populace was being starved into submission, the German State was being divided – and not just upon East/West lines. The Saar region, nominally administered by France, was granted a measure of autonomy as a protectorate under French rule. The Saar had been under the same status after World War I, as the region hadn’t formally rejoined Germany until 1935. In both cases, the French had exploited the mineral-rich valley, and attempted to foster at least anti-Prussian, if not pro-French, sentiments with the population. Pro-German unification parties were banned by the French in the Saar’s one independent election in 1952, but a clear majority of voters appeared to support autonomy. Yet, after substantial Allied pressure, the French allowed a referendum on reunification in 1955, with the measure passing with nearly 68% of the vote.

It had been a decade, but at least West Germany was unified.

A pro-unification cartoon on the Saar referendum, warning that the Saar risked becoming “trapped” by France. Still, 32% of the region voted for autonomy

—

The Allied policy towards Germany had been off-shoot the so-called Morgenthau Plan – a brainchild of U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau which called for a series of policies to deliberately weaken Germany, transforming her from an industrial to an agricultural state. This new, weakened Germany, would be unable to re-arm herself and thus, no longer be a threat to her neighbors.

While the Morgenthau Plan itself was never adopted, the belief that Germany could be fundamentally transformed into a weak state by de-industrialization provided the foundation of the Allies’ early years of the occupation. But as the Allies discovered that a weak Germany could barely feed herself, Allied attitudes slowly began to soften. “There is the illusion that the New Germany left after the annexations can be reduced to a ‘pastoral state'”, stated former President Herbert Hoover in 1947 after touring the country for a report for Harry Truman. “It cannot be done unless we exterminate or move 25,000,000 people out of it.” The Soviets were clearly comfortable with such actions – the West wasn’t.

A collapsed laborer in Germany – a common site in the late 40s

To rebuild, Germany need capital – a lot of it. Hoover, and others, had noted to Truman that the real illusion was that the Europe could economically recover to pre-war standards without a strong German economy. Germany had long had a trade surplus in the inter-war years, exporting raw materials and processed goods, driving German GDP to the 10-11% range by the late 30s. Unless Germany returned to her pre-war role as a major supplier to European markets, Europe’s recovery would lag behind.

Thus the Marshall Plan was born. Led by former Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, acting then as Secretary of State, the Marshall Plan funneled $13 billion in U.S. aid to European allies and enemies alike. Another $13 billion was given under programs not directly linked to the Plan, and yet another $7 billion per year was awarded under the Marshall Plan’s successors until 1961. That’s $124 billion in all – or over $1.3 trillion in today’s dollars.

While rebuilding the German economy was highly controversial, West Germany was only the third-highest recipient of the aid. Britain and France received far more money from the Plan, with Italy and the Netherlands getting similar amounts of aid to Germany. Nevertheless, with massive amounts of money heading overseas – often to nations that had killed or wounded thousands of American soldiers – opposition to the Marshall Plan was heated. Congressional Republicans made decent gains in 1950, still coming up short of a majority in either chamber, but managing to defeat the Senate’s Democratic Majority Leader Ernest McFarland.

Anti-Marshall Plan demonstrations – the Soviets claimed the Plan was an imperialist plot. That didn’t stop some Eastern European nations like Yugoslavia from taking the aid

So what did America get for it’s $124 billion? Industrial production in Europe jumped by 35%, but it’s debatable how much the jump truly kick-started European markets. The Marshall Plan definitely cemented the East/West divide – as poverty-stricken Soviet satellites were forced to reject the funds in favor of weaker Soviet aid packages. Yet, by 1948, most of the Eastern European bloc was back to pre-war economic standards – just as Western Europe was.

The return on the Marshall Plan was almost certainly more political than economic. With France rebuilding, and England broke, the United States demonstrated the economic standing to go with it’s military standing as the leader of the Western Allies. Nations that were on the edge of the East/West divide – such as Italy or Greece – fell firmly into the Western camp. The Marshall Plan had fairly literally bought the West it’s allies for the burgeoning Cold War.

The stage for the next nearly 50 years – and the rest of history – had been set.

—

We’ve enjoyed bringing you this 70th anniversary series on World War II from SITD’s first formal post waaay back in 2009. You can re-read the whole series here.

I recommend the book “exorcising Hitler”. It’s about the de-nazification of Germany.

One of the items mentioned is what you refer to above. There we calls to break Germany up into little countries. None with any industrial or even mining capacity or abilities.

In the end, they (allies) classified Nazi parties members based on how active they were in the party. Some were just low level government drones who were forced to join the party as a condition of employment, on up to war-criminal at the top. These codes were used to decide who we could allow to have a role in post-war Germany (mayors, police, judges, even city clerks).

And the story about how the Nazi party membership database was saved from burning in April of 1945 is interesting. I won’t give it away.

My dad served on the USS Taylor (DD468). It was the first US Ship to steam into Tokyo Bay.

The Marshall Plan cost (if Wikipedia is to be believed) about $130B in today’s dollars.

The War on Poverty has cost about $22T.

We might ask which has been the better investment.

How did Mac keep the Soviets off of Hokkaido? I don’t think I’ve ever heard of how this played out.

Bubba – you’re right on the figures for the Marshall Plan itself. However, there were a number of other US aid/loan programs, giving sums far greater than the $13 billion the Plan is directly credited for. If you add pretty much all of them up, and factor in CPI, you’ll get a rough estimate of $1.3 trillion in current dollars. I’m sure a more detailed historian could probably find even more post-war spending.

NW – the Soviets had intended to invade Hokkaido in late August as a follow-up to their Manchurian attack. Prior conferences had assigned the island to the Soviets in post-war Japan. Truman already started to rethink the policy when he warned Stalin at Potsdam not to invade Hokkaido. Then when MacArthur arrived, he moved a fair number of the (going off of memory here) 350,000 US soldiers north. Between the State Department and Mac, the Hokkaido offer was essentially revoked.